The evolution of classical computing and quantum computing share similarities and differences, each with unique milestones pushing the boundaries of computation and information processing. In the early 20th century, classical computing commenced with theoretical foundations by individuals like Alan Turing and John Von Neumann. Turing introduced the concept of a theoretical computing machine, the Turing machine, in 1936, which formed the basis of classical bit-based computation. Around the same time, quantum mechanics was being formalized, setting the stage for the future development of quantum computing.

Classical computing saw its first tangible form with the creation of electronic computers in the 1940s, such as the ENIAC. Over the decades, advances in semiconductor technology led to an exponential increase in computing power, as encapsulated by Moore’s Law. Classical bits serve as the fundamental information units in classical computing, existing in a binary state of either 0 or 1.

Quantum computing, on the other hand, began its journey much later, with theoretical foundations laid in the early 1980s by Paul Benioff, Richard Feynman, and David Deutsch. They proposed the idea of leveraging quantum mechanical properties to process information. Unlike classical bits, quantum bits or qubits can exist in a superposition of states, embodying both 0 and 1 simultaneously, which underpins the potential for exponential computational speedups.

Theoretical Foundations of Quantum Computers

In classical computing, the theoretical foundation was laid down primarily in the early to mid-20th century. Notably, Alan Turing introduced the concept of a theoretical computing machine in 1936, which could solve any problem described by simple instructions encoded on a tape. This theoretical model provided the conceptual framework for classical computing, highlighting the potential of automated computation. John Von Neumann’s work later in the 1940s further enriched the theoretical underpinning of classical computing, providing a structure for stored-program computers that became a standard architecture in the subsequent development of computers.

Quantum computing, conversely, had its theoretical roots planted in the early 1980s. The seminal works by Paul Benioff, Richard Feynman, and more in the early 1980s proposed the idea of quantum computation, illustrating the possibility of leveraging quantum mechanical properties like superposition and entanglement to process information in a way that classical computers could not.

Later in the 1990s, useful algorithms such as Deutsch-Josza, Shor, and Grover provided that Quantum Computers could do something unique by computing algorithms that would take conventional classical computers near eternity. This set the field alight, for Shor’s Algorithm could break encryption, Grover’s could more effectively search and there was the beginning of the purported usefulness of quantum computing.

Industrial Involvement

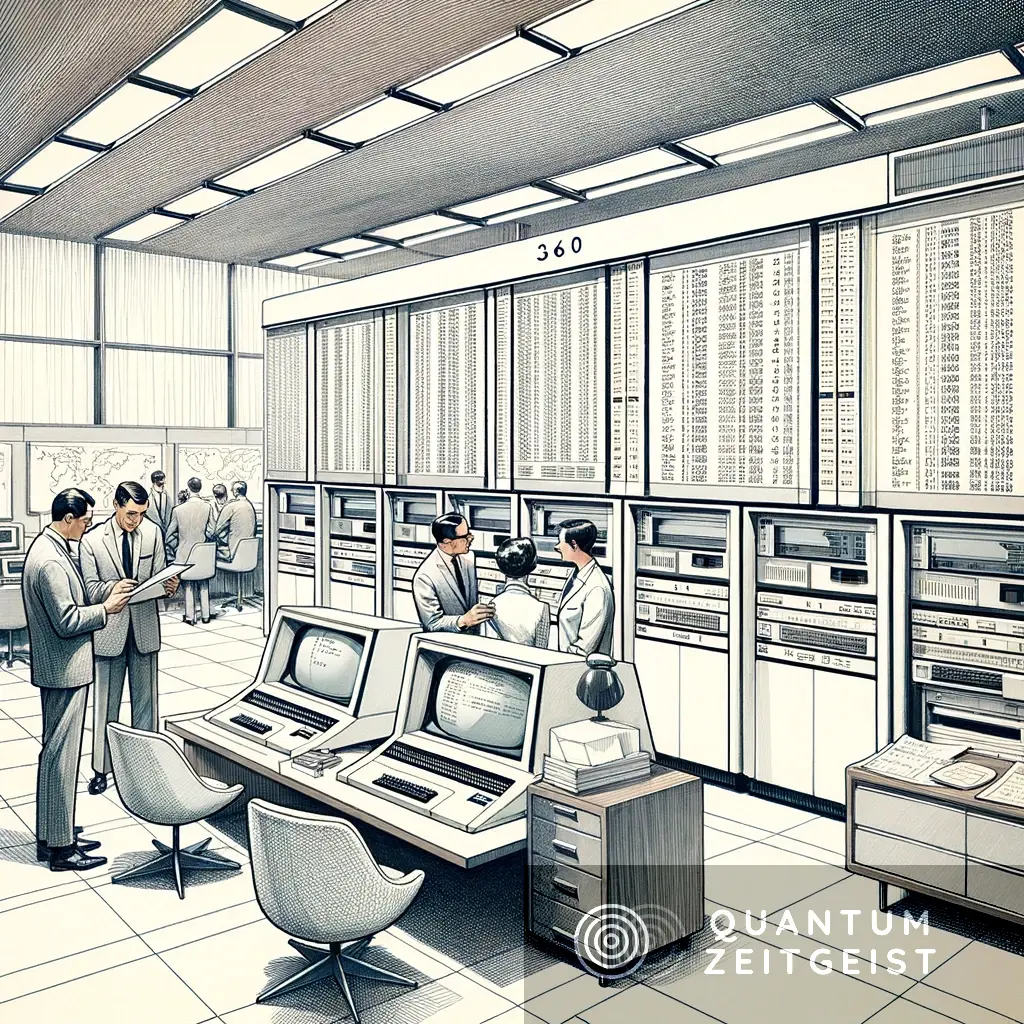

The early days of classical computing saw significant industrial involvement, with companies like IBM, Intel, and Microsoft emerging as key players. Their investments and innovations in hardware and software greatly accelerated the development and commercialization of classical computing technology. For instance, IBM’s development of the 701 Electronic Data Processing Machine in 1952 marked one of the early instances of industrial-scale computers, which was soon followed by a series of other computing machines that catered to both scientific and business applications.

In quantum computing, the involvement of industry has been pivotal as well, albeit at a much later stage compared to classical computing. Companies like IBM, Google, Xanadu, IonQ and Rigetti Computing have been at the forefront of quantum computing research and development. For instance, IBM introduced its quantum computing program, IBM Quantum, aiming to build commercially viable quantum computers. Similarly, Google’s achievement of quantum supremacy in 2019 marked a significant milestone in the quantum computing landscape, showcasing the potential for quantum computers to solve certain problems faster than classical computers.

The industrial engagement in classical and quantum computing showcases a consistent trend where private sector involvement significantly accelerates technological advancements. However, the quantum era has also seen a more collaborative approach, with academia, industry, and government entities often working together to overcome the unique challenges of quantum technology. Quantum computing and the multidimensional challenges that lie ahead.

Hardware Evolution in Quantum Computers

Classical computing hardware evolved rapidly from the 1940s onwards, with milestones like the transition from vacuum tubes to transistors in the 1950s, and subsequently to integrated circuits in the 1960s. These transitions marked significant leaps in computing power, miniaturization, and energy efficiency. The invention of the microprocessor in the 1970s further propelled the capabilities and accessibility of classical computing, paving the way for the personal computing revolution.

Quantum computing hardware, on the other hand, is still in a nascent stage, with ongoing efforts to build scalable and fault-tolerant quantum computers. The development of quantum bits (qubits) and quantum gates, which are fundamental to quantum computing, poses significant challenges due to the fragile nature of quantum states. However, milestones such as IBM’s development of a 50-qubit machine and Google’s 54-qubit Sycamore processor showcase quantum hardware’s gradual but promising evolution. IBM now has a machine with 433 Qubits and is on track to deliver over 1,000 Qubits next year, according to its roadmap.

However, there are plenty of Qubit hardware types, such as Ion Trap, Superconducting, Photonic, and semi-conducting. Contrast this to the very silicon-centric path that classical computing took.

The comparison of hardware evolution between classical and quantum computing reflects a diverging path. While classical computing saw a relatively steady progression with breakthroughs quickly translating to commercial applications, quantum computing potentially faces a more arduous journey. The delicate nature of quantum information and the requisite for maintaining coherence and mitigating errors present formidable challenges that necessitate a collaborative and multi-disciplinary approach to overcome. The promise of quantum computing is vast, but the hardware evolution underscores a meticulous and incremental path toward realizing practical quantum computers.

The Key Parallels Between Classical and Quantum Computing

Drawing parallels, the development of classical computing was significantly driven by industrial involvement, with companies like IBM, Intel, and Microsoft playing pivotal roles. Similarly, in the quantum realm, companies like IBM, Google, Rigetti, Xanadu, IonQ are at the forefront of pushing quantum technology forward.

Moreover, classical computing milestones, such as the development of integrated circuits in the 1960s and the microprocessor in the 1970s, accelerated the growth and accessibility of computing technology. Similarly, the ongoing quest for scalable and fault-tolerant quantum computers is a milestone that the quantum computing community aspires to achieve.