Life, at its core, is a defiance of entropy. While the second law of thermodynamics dictates a relentless march towards disorder, living organisms maintain remarkable order, complexity, and functionality. This isn’t a violation of physics, but a masterful exploitation of non-equilibrium statistical mechanics, a field that explores systems driven far from equilibrium, where traditional thermodynamic descriptions break down. For decades, physicists considered equilibrium the natural state of matter, but the realization that life requires disequilibrium has spurred a revolution in our understanding of both biology and physics. This field, initially developed by physicists like Lars Onsager, who received the Nobel Prize in 1968 for his work on irreversible thermodynamics, provides the framework for understanding how living systems harness energy to create and maintain order. It’s a world where fluctuations aren’t just noise, but the very engine of innovation and adaptation.

The foundations of non-equilibrium statistical mechanics were laid by Ilya Prigogine, a Nobel laureate and professor at the Free University of Brussels. Prigogine challenged the classical view of systems tending towards a uniform, stable equilibrium. He proposed that systems driven far from equilibrium can self-organize into what he termed “dissipative structures.” These structures, like Bénard cells, convection patterns formed in a heated fluid, maintain their order by continuously dissipating energy. Crucially, Prigogine demonstrated that these structures aren’t simply temporary deviations from equilibrium, but fundamentally new states of matter, exhibiting emergent properties not present in the individual components. This concept is profoundly relevant to biology, where complex structures like cells, tissues, and even organisms are maintained through constant energy flow and dissipation. The very existence of life, Prigogine argued, is a testament to the power of dissipative structures.

From Thermodynamics to Information: The Role of Fluctuations

Traditional thermodynamics focuses on macroscopic properties, averaging out the chaotic dance of individual molecules. However, in non-equilibrium systems, fluctuations, random deviations from the average, become amplified and play a crucial role. These aren’t merely disturbances to be ignored; they are the seeds of change, the drivers of innovation. As Rolf Landauer, a physicist at IBM Research, established in 1961, erasing information requires energy dissipation. This connection between information and thermodynamics is central to understanding how living systems process information and respond to their environment. Fluctuations allow systems to explore different states, and if a fluctuation leads to a more stable, energy-efficient configuration, it can be amplified and sustained, leading to the emergence of new structures and behaviors. This is akin to natural selection at the molecular level, where beneficial fluctuations are favored and propagated.

The Minimal Dissipation Principle and Biological Efficiency

Living systems aren’t just complex; they are remarkably efficient. They operate far from the theoretical limits of energy expenditure predicted by classical thermodynamics. This efficiency is explained by the minimal dissipation principle, a cornerstone of non-equilibrium statistical mechanics. This principle states that systems driven far from equilibrium will self-organize to minimize the rate of energy dissipation. In essence, organisms aren’t simply fighting against entropy; they are cleverly navigating the landscape of energy flow to minimize waste and maximize functionality. This principle is evident in everything from the streamlined shape of a fish to the intricate network of capillaries in our bodies, all designed to minimize resistance and maximize efficiency. Understanding this principle is crucial for bioengineering and the development of sustainable technologies.

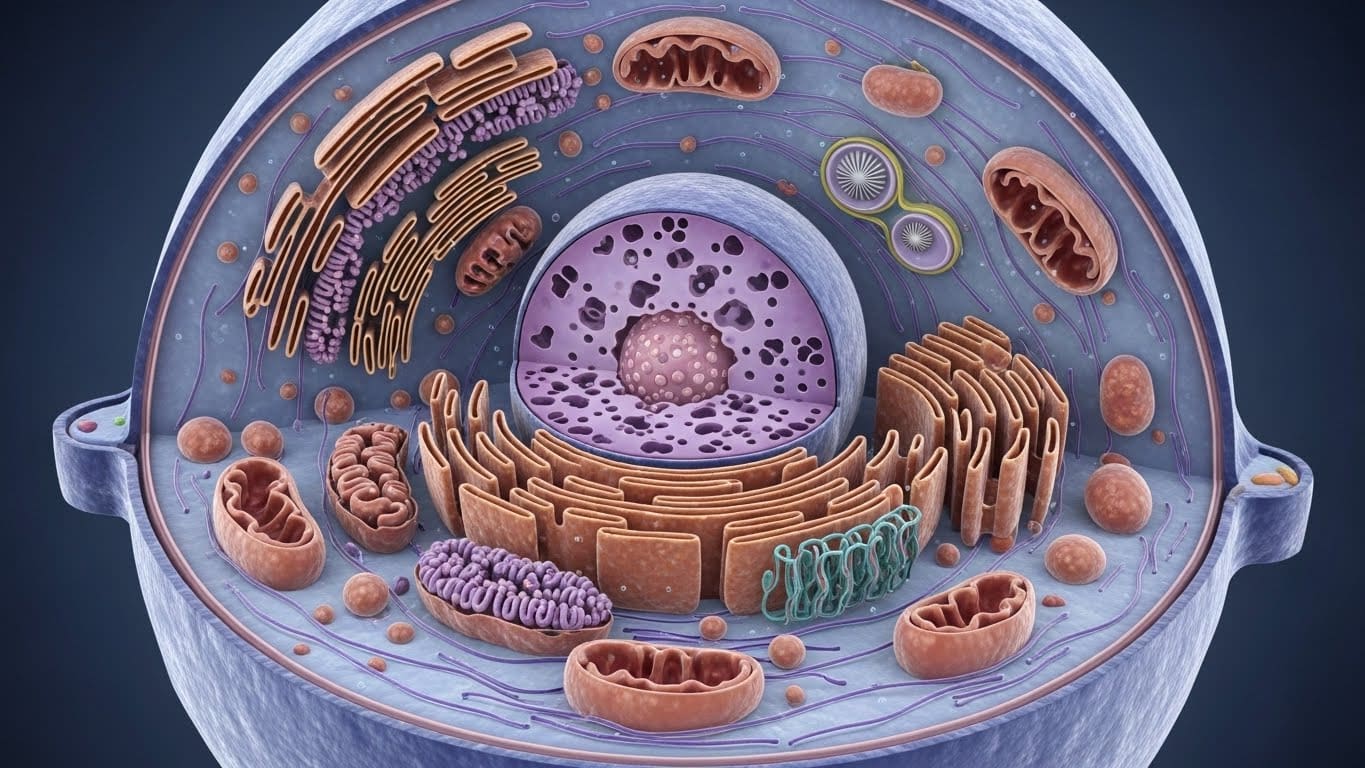

The Cytoplasm as a Condensate: A New View of Cellular Organization

For decades, the cytoplasm of a cell was viewed as a homogenous soup of molecules. However, recent research, heavily influenced by non-equilibrium principles, reveals a far more complex picture. The cytoplasm is now understood to be a highly organized, dynamic environment filled with membraneless organelles formed through a process called liquid-liquid phase separation. These condensates, akin to oil droplets in water, concentrate specific molecules, creating microenvironments that enhance reaction rates and regulate cellular processes. These condensates aren’t static structures; they are constantly forming, dissolving, and rearranging in response to cellular signals, driven by fluctuations and energy dissipation. This dynamic organization allows cells to rapidly adapt to changing conditions and perform complex tasks with remarkable efficiency.

Active Matter and the Self-Propelled World of Microorganisms

Non-equilibrium statistical mechanics isn’t limited to passive systems; it also provides a framework for understanding “active matter”, systems that consume energy to drive their own motion. Microorganisms, like bacteria and algae, are prime examples of active matter. They don’t simply respond to external forces; they actively generate forces, creating collective behaviors that defy traditional physics. These organisms can self-organize into swirling patterns, form biofilms, and even exhibit collective decision-making. This behavior is driven by the interplay between individual motility, hydrodynamic interactions, and energy dissipation. Understanding the principles governing active matter is crucial for developing new materials with self-propelling capabilities and for controlling microbial communities.

The Physics of Development: Shaping Form from Chaos

The development of an organism from a single cell is a breathtaking example of self-organization. How does a seemingly homogenous zygote give rise to the intricate complexity of a fully formed organism? Non-equilibrium statistical mechanics provides a powerful framework for understanding this process. Development isn’t a pre-programmed sequence of events, but a dynamic process driven by fluctuations, energy gradients, and feedback loops. Pattern formation, such as the development of limbs or the segmentation of the body, can be explained by reaction-diffusion systems, mathematical models that describe how interacting chemicals create spatial patterns. These patterns aren’t imposed from the outside; they emerge spontaneously from the interplay of local interactions and energy dissipation.

The Role of Noise in Gene Expression: Beyond Deterministic Models

Traditionally, gene expression was viewed as a deterministic process, where genes are transcribed and translated into proteins with predictable accuracy. However, recent research reveals that gene expression is inherently noisy. Fluctuations in the number of mRNA molecules, ribosomes, and other cellular components lead to significant variations in protein levels, even among genetically identical cells. This noise isn’t simply a nuisance; it can be beneficial. It allows cells to explore different phenotypes, increasing their adaptability and resilience. Furthermore, noise can act as a switch, triggering different developmental pathways or enabling cells to respond to subtle environmental cues. David Deutsch, the Oxford physicist who pioneered quantum computing theory, has even suggested that quantum fluctuations may play a role in the initial stages of gene expression.

Metabolic Networks as Dissipative Engines

Metabolism, the sum of all chemical reactions that occur within an organism, is a prime example of a non-equilibrium process. Living cells constantly consume energy to maintain their metabolic pathways, driving reactions that would otherwise be thermodynamically unfavorable. Metabolic networks aren’t simply linear pathways; they are complex, interconnected webs of reactions that exhibit emergent properties. These networks are optimized to minimize energy dissipation and maximize the production of essential biomolecules. Understanding the principles governing metabolic networks is crucial for developing new therapies for metabolic diseases and for engineering synthetic metabolic pathways.

While non-equilibrium statistical mechanics provides a powerful framework for understanding biological systems, it also highlights the inherent limits of predictability. Many biological systems exhibit chaotic behavior, meaning that small changes in initial conditions can lead to dramatically different outcomes. This sensitivity to initial conditions makes it impossible to predict the long-term behavior of these systems with perfect accuracy. However, even in chaotic systems, there are underlying patterns and constraints. Non-equilibrium statistical mechanics allows us to identify these patterns and understand the system’s statistical properties, even if we cannot predict its exact trajectory. Gil Kalai, the Hebrew University mathematician known for quantum computing skepticism, often points out the inherent unpredictability of complex systems, emphasizing the need for probabilistic models rather than deterministic predictions.

The principles of non-equilibrium statistical mechanics aren’t limited to biology. They are relevant to a wide range of physical phenomena, from the formation of galaxies to the dynamics of climate change. The universe itself is a far-from-equilibrium system, constantly evolving and dissipating energy. Understanding the principles governing non-equilibrium systems is crucial for unraveling the mysteries of the cosmos and for addressing some of the most pressing challenges facing humanity. The study of non-equilibrium statistical mechanics is not just a quest to understand life; it’s a quest to understand the fundamental laws that govern the universe itself.