All standard computers rely on classical bits for storage. Quantum Computers employ qubits – or quantum bits instead of those classical bits. Before we move on to understanding the qubit, we’ll briefly examine the classical bit and how to manipulate it, then move on to the quantum bit or qubit.

Introduction to The Qubit

Binary representation: The Classical Bit.

The words and text you view now are stored as binary representations of 0 and 1. Everything, whether a letter, number, or image, is represented at the most fundamental level of a string of 0s and 1s. So, for example, the number 5 can be represented as 101 and the number 1 as 001. Such a binary scheme can store 8 states because, for each bit, there are 2 possible states: 0 or 1. That means there are 2 x 2 x 2 = 8 states, 2^3 states. More generally, we can specify the number of states as 2^n, where n is the number of bits. If you wanted to store every alphabet letter, you need 26 states; the nearest factor of 2 that stores this number of states is 32. So this means we need 5 bits, giving us 2^5 = 32 possible states with six spare states. Typical schemes such as ASCII use 8 bits, and each unit of 8 bits describes a character.

Why use binary? Why not an analog representation?

There are many reasons to use binary states, even though it may initially seem very odd. Namely, the representation of data is then unquestionable. A letter cannot change easily. You can imagine an analog computer could store letters with voltages; imagine the eight-state can above; we could store using eight different voltages. Such schemes exist, but the issue with analog states is how to deal with them smartly. Analog computers must perform addition with analog representations. What does bit stand for? Just for completeness, the bit stands for binary digit. A shortened version, Simple!

For example, suppose we store two different numbers in an analog representation. In that case, there will always be some precision limit by which adding the numbers together will lead to inaccuracies because we cannot use infinite voltages; we must scale representations. For example, if we store 23 and 42 with the voltages 0.23V and 0.42V, then if we add these together, we should get 0.65V, representing 65. But we have had to introduce some degree of rounding, and if our machine can only deal with 0.1 precision, we may only be able to store 0.2V and 0.4V, which means the sum of 0.2V and 0.4V gives 0.6V or 60 (approximating 65). Eventually, errors propagate by the build-up of minor deviations and limited precision, making calculations unreliable.

Example of binary addition

Using a binary representation (with a MAXIMUM of 2^8 = 256 states), we can do this addition without losing accuracy. For example:

| Binary | Decimal |

|---|---|

| 00010111 | 23 |

| + | + |

| 00101010 | 42 |

| = | = |

| 01000001 | 65 |

We represent the number (23,42,65) as binary. Note that we assume that the bits on the left are most significant. I’ll explain how this works with a simpler case. For example, take 65, all zeros, and two 1’s. The position of these is significant. Now, in binary, we count in powers of two. That means we have 8 bits from the leftmost position (0) 128. This makes sense because we should not have any amount of 128, as 65 is much smaller. However, move along to the next bit (left to right), and the bit represents 64. We should take this position (with a 1) as 64 is less than 65, the number we want to represent. We are just one away from summing to our target of 65. The rightmost bit represents 1, so let’s put a (1) there and sum. Hence, we get the representation 65 from 01000001.

| 128 | 64 | 32 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 2 | 1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2^7 | 2^6 | 2^5 | 2^4 | 2^3 | 2^2 | 2^1 | 2^0 |

| 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

An easy introduction to the world of Quantum Computing

Now you understand bits (hopefully) and how to do a simple operation with them, let’s move on to the differences and how a Qubit is different, how we work with them, and how to represent them. The most crucial part to remember regarding qubits or Quantum Bits (Qubits) is there are not just two states, as we saw in the binary case above. There are other attributes, as you would expect, but the uniqueness of quantum is that there are just 0 or 1. Qubits can be very complex, as can the mathematical tools used to represent and manipulate them. By giving you a taste of some of these simple operations, we hope to inspire you Quantumly.

The Qubit: Representing a Qubit

We need a form allowing our Qubit representation to take on many states. In reality, we cannot know precisely what these states represent because there are some limitations with the measurement of the Qubit. One of the tenets of the Quantum field is that measurements are essentially statistical and probabilistic. This means we could have a state, Q, that represents a 0 40% of the time and a 1 60% of the time. If we were to flip ten coins, we would expect tails 60% of the time and heads 40% of the time. But flipping an individual coin would not tell us about our distribution of states.

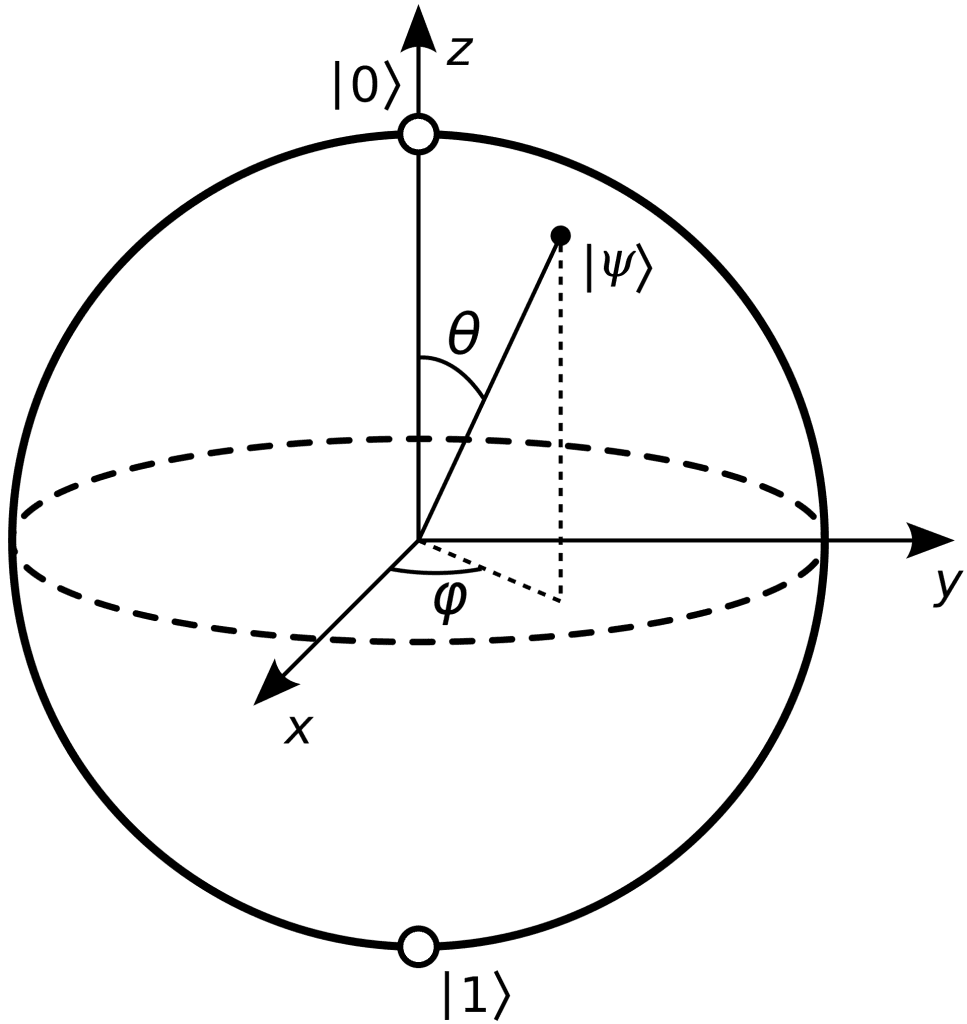

Mathematicians have a representation of the quantum state that adheres to this statistical representation. They also have very clever mathematical language, making writing down and manipulating these states easier. We’ll encounter a few of these states because interoperating between these schemes will be very useful. One of the key ways that we can visualize The Qubit is with something named the Bloch Sphere.

Matrix and Vector form of the Qubit

Mathematicians use Matrix forms, but you don’t need to understand much about them here to understand this example. As you saw earlier, we must have a probabilistic interpretation of 0 and 1. We can do this with a matrix or a simple column vector. One form of the column representation is fully 0, and the other is entirely 1.

Representing a zero state (0)

Representing a one state (1)

OK, so what? Well, if we had just two states, that would be boring, wouldn’t it? Quantum states can be in a mixed state. That means that we can have a blend of these two states. Let’s show that in vector form using two terms, alpha and beta. So now we have a blend of two states; you might call it a superposition of states, a mix of 0 and 1. But aha, we need to ensure that alpha and beta are constrained. Because we are dealing with probabilities, we know that the measurement of the qubit must be constrained to be within the range of 0 to 1.

We can now specify two co-coefficients that we can use to scale how much we want of state 0 and state 1. So, we can have a superposition of states—an essential concept in Quantum Mechanics.

Lets now create a combination of these two states

The constants alpha and beta can take values such that the total probability is never over 1 and maximally at 1. So if we wanted to have all in state 0, alpha would be equal to 1 () and beta equal to zero (

).

Measuring a Qubit

For a single qubit, we have the following constraint that

This means that we have constraints. Let’s see some examples of if we wanted to have a state as likely to be in state 0 as in state 1. This means that and an equal superposition of a single Qubit looks like

Multiple states of the Quantum Qubit

Before, we saw some simple ways we could combine two states. The many states our single qubit can take make quantum computing very powerful. But before we do anything else, we should note that matrix or vector notation can be cumbersome for writing down relations in the Quantum field, so bring on Dirac notation.

Dirac Notation (those bra and kets)

Paul Dirac, one of the kings of mathematics and Quantum, created notation to make dealing with Quantum states easier. He created the following (bra and ket’s)

The ket notation

This is a column vector, as we saw above; here it is again

and is denoted with an angled bracket as follows for a state fully in 0 and

for a state fully in 1. Kets are typically used for the state of the quantum system.

The bra notation

This is a row vector, basically the transpose of a column vector. Just for completeness but we won’t worry about it here.

Now, we can write our earlier expression of the equal superposition as

Measuring a Qubit State

If we were to measure the Qubit we had before in the equal superposition, here is what we might get. Note that we only measure a state each time. The state of our Qubit is either measured in state 0 or state 1, but for the limited number of measurements, we see an equal number of each state represented. Of course, six measurements is shallow, and we all know that low numbers in statistics can lead to issues. So, we might need 1000 measurements before we see the level of precision in measuring an equal superposition of states.

But we would see a 50/50 split between these two states on balance. This means we have a probability of being in state 0 as 0.5 and state 1 as 0.5. More formally, if we were to look at the Dirac or matrix notation, we would see that the measurement in state 0 or state 1 is

In summary, if we could run this stochastic experiment an infinite number of times, the equal superposition would yield state 0 with probability 0.50000000000… (you get the drift) and state 1 with probability 0.50000000000…