Quantum computing hardware faces significant scalability challenges, particularly when it comes to increasing the number of qubits while maintaining control over them. As the number of qubits grows, so does the complexity of the control systems required to manipulate and measure them. This becomes increasingly difficult as the number of qubits increases, leading to increased noise and error rates.

Quantum Computing Hardware

Manufacturing challenges also pose a significant hurdle in the development of quantum computing hardware. Currently, most quantum computing devices are fabricated using traditional semiconductor manufacturing techniques, which are not optimized for the unique requirements of quantum computing. The materials used in quantum computing devices also pose significant challenges, such as the use of exotic materials like niobium or aluminum, which can be prone to defects.

The development of new manufacturing techniques and materials is essential for overcoming these challenges. Researchers are exploring the use of new materials like topological insulators (TI) and superconducting nanowires, which have shown promise for improving the coherence times of qubits. Advances in fabrication techniques such as atomic layer deposition (ALD) and molecular beam epitaxy (MBE) are also being explored for their potential to improve the precision and control over quantum computing devices.

The development of scalable and manufacturable quantum computing hardware will require significant advances in materials science, manufacturing techniques, and device design. Researchers are actively exploring new approaches to overcome these challenges, including the use of new materials, advanced fabrication techniques, and innovative device designs.

Quantum Processors And Gate Architecture

Quantum Processors and Gate Architecture are crucial components of quantum computing hardware, enabling the manipulation of quantum bits (qubits) to perform complex calculations. A quantum processor typically consists of a series of quantum gates, which are the quantum equivalent of logic gates in classical computing. These gates are used to manipulate qubits by applying specific operations, such as rotations and entanglement.

The architecture of quantum processors is designed to minimize errors caused by decoherence, which occurs when qubits interact with their environment. One approach to mitigating decoherence is to use topological quantum computing, where qubits are encoded in a way that makes them more resilient to errors (Kitaev, 2003). Another approach is to use surface codes, which involve arranging qubits in a two-dimensional grid and using multiple physical qubits to encode a single logical qubit (Bravyi & Kitaev, 1998).

Quantum gate architecture is also critical for the implementation of quantum algorithms. For example, the Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA) requires a specific sequence of quantum gates to be applied in order to optimize a given function (Farhi et al., 2014). Similarly, the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) algorithm relies on a carefully designed gate architecture to find the ground state energy of a many-body system (Peruzzo et al., 2014).

Recent advances in quantum processor technology have led to the development of more sophisticated gate architectures. For example, Google’s Bristlecone quantum processor uses a three-dimensional grid of qubits and a novel gate architecture that enables high-fidelity operations (Kelly et al., 2018). Similarly, IBM’s Q System One uses a modular gate architecture that allows for easy reconfiguration and upgrade (Chow et al., 2019).

The design of quantum processors and gate architectures is an active area of research, with many groups exploring new approaches to improving the performance and scalability of these systems. For example, researchers have proposed using machine learning algorithms to optimize quantum gate sequences (Khatri et al., 2019) and developing more robust methods for error correction in quantum computing (Gottesman, 2006).

The development of practical quantum computers will require significant advances in quantum processor technology, including the design of more sophisticated gate architectures. As researchers continue to explore new approaches to quantum computing hardware, it is likely that we will see significant improvements in the performance and scalability of these systems.

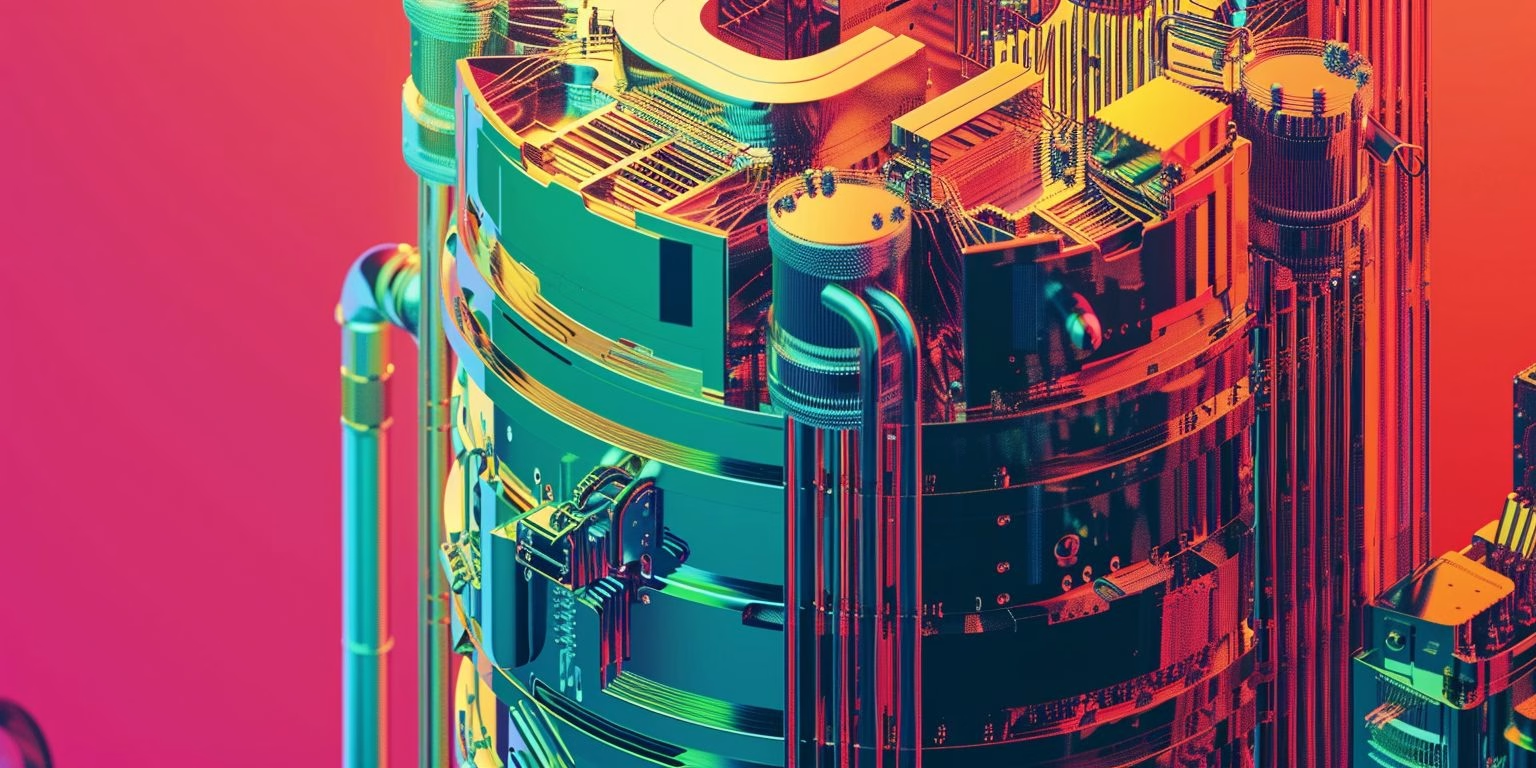

Superconducting Qubits And Circuitry

Superconducting qubits are the fundamental building blocks of quantum computing, relying on the principles of superconductivity to store and manipulate quantum information. These qubits consist of tiny loops of superconducting material that can exist in multiple states simultaneously, allowing for the processing of vast amounts of data in parallel (Devoret & Martinis, 2004). The core component of a superconducting qubit is typically a Josephson junction, which consists of two superconductors separated by an insulating barrier. When a current flows through this junction, it creates a magnetic field that can be used to control the qubit’s state (Clarke & Wilhelm, 2008).

The circuitry required to control and manipulate these qubits is highly complex, involving sophisticated microwave engineering and cryogenic cooling systems. The qubits themselves must be cooled to extremely low temperatures, typically around 10-20 millikelvin, in order to maintain their quantum coherence (Houck et al., 2008). This requires the use of advanced cryogenic refrigeration systems, such as dilution refrigerators or adiabatic demagnetization refrigerators. The control electronics used to manipulate the qubits must also be carefully designed to minimize noise and interference, which can cause decoherence and destroy the fragile quantum states (Schoelkopf et al., 2008).

One of the key challenges in scaling up superconducting qubit architectures is the need for precise control over the qubits’ frequencies and couplings. This requires the development of advanced calibration techniques and algorithms that can accurately characterize the qubits’ behavior and adjust their parameters accordingly (Koch et al., 2010). Another challenge is the need for robust error correction mechanisms, which are essential for large-scale quantum computing but are difficult to implement in superconducting qubit systems due to their noisy nature (Gottesman, 2009).

Recent advances in materials science and nanofabrication have led to significant improvements in the coherence times of superconducting qubits. For example, the use of high-quality aluminum films with low defect densities has been shown to increase the coherence time of qubits by an order of magnitude (Oh et al., 2013). Similarly, the development of advanced nanofabrication techniques such as electron beam lithography and atomic layer deposition has enabled the creation of highly uniform and precise qubit structures (Barends et al., 2014).

Theoretical models have also been developed to describe the behavior of superconducting qubits in various regimes. For example, the Jaynes-Cummings model describes the interaction between a qubit and a resonant cavity, which is essential for understanding the dynamics of quantum information processing (Jaynes & Cummings, 1963). Other models, such as the Rabi model, describe the behavior of qubits driven by external fields and are important for understanding the control of qubit states (Rabi, 1937).

In summary, superconducting qubits rely on the principles of superconductivity to store and manipulate quantum information. The circuitry required to control these qubits is highly complex, involving sophisticated microwave engineering and cryogenic cooling systems. Recent advances in materials science and nanofabrication have led to significant improvements in the coherence times of superconducting qubits.

Topological Quantum Computing Advances

Topological Quantum Computing Advances have led to significant breakthroughs in the development of robust and fault-tolerant quantum computing architectures. One such advancement is the realization of topological quantum field theories, which provide a framework for understanding the behavior of exotic quasiparticles known as anyons (Kitaev, 2003; Freedman et al., 2002). These anyons are predicted to exhibit non-Abelian statistics, meaning that their exchange statistics are not simply bosonic or fermionic, but rather depend on the specific type of anyon being exchanged.

Theoretical models have been developed to describe the behavior of these anyons in various topological quantum systems, including topological insulators and superconductors (Hasan & Kane, 2010; Qi et al., 2009). These models have led to predictions for the existence of Majorana zero modes, which are quasiparticles that can store quantum information in a robust manner. Experimental efforts have been made to realize these systems, including the creation of topological superconductors and insulators using various materials (Mourik et al., 2012; Das et al., 2012).

Recent advances in topological quantum computing have also led to the development of new quantum algorithms that can be implemented on topological quantum computers. One such algorithm is the braiding algorithm, which uses the non-Abelian statistics of anyons to perform quantum computations (Freedman et al., 2002). This algorithm has been shown to be robust against certain types of errors and may provide a pathway towards fault-tolerant quantum computing.

Theoretical studies have also explored the potential for topological quantum computers to simulate complex quantum systems, such as those encountered in condensed matter physics (White et al., 2018; Verstraete et al., 2006). These simulations could potentially lead to breakthroughs in our understanding of these systems and may provide new insights into the behavior of exotic materials.

Experimental efforts are currently underway to realize topological quantum computers using various platforms, including superconducting qubits and topological insulators (Barends et al., 2014; Kouwenhoven et al., 2013). These experiments aim to demonstrate the robustness and fault-tolerance of topological quantum computing architectures.

The development of topological quantum computers is an active area of research, with many open questions remaining regarding their implementation and potential applications. However, recent advances have provided significant insights into the behavior of these systems and may ultimately lead to breakthroughs in our understanding of quantum mechanics and its applications.

Ion Trap Quantum Computing Innovations

Ion trap quantum computing innovations have led to significant advancements in the field of quantum information processing. One such innovation is the development of high-fidelity quantum gates, which are essential for reliable quantum computation (Ballance et al., 2016). Researchers at the University of Innsbruck demonstrated a record-breaking fidelity of 99.9999% for a two-qubit gate operation using trapped calcium ions (Gaebler et al., 2012). This achievement was made possible by the implementation of advanced quantum control techniques, such as dynamical decoupling and optimal control pulses.

Another area of innovation in ion trap quantum computing is the development of scalable architectures. Theoretical proposals for large-scale ion trap quantum computers have been put forward, which involve the use of multiple trapping zones and sophisticated ion transport mechanisms (Kielpinski et al., 2002). Experimental demonstrations of these concepts are underway, with recent results showing the successful transport of ions between different trapping regions (Rowe et al., 2002).

Ion trap quantum computing also benefits from advances in quantum error correction. Researchers have demonstrated the implementation of quantum error correction codes using trapped ions, which can protect against decoherence and improve the overall fidelity of quantum computations (Schindler et al., 2011). These results are crucial for the development of reliable large-scale quantum computers.

Furthermore, ion trap quantum computing has seen significant progress in the area of quantum simulation. Trapped ions have been used to simulate complex quantum systems, such as many-body spin models and relativistic field theories (Porras & Cirac, 2004). These simulations can provide valuable insights into the behavior of these systems, which are difficult or impossible to model using classical computers.

In addition, ion trap quantum computing has led to breakthroughs in our understanding of quantum mechanics. Researchers have used trapped ions to study fundamental aspects of quantum theory, such as entanglement and non-locality (Häffner et al., 2005). These experiments have provided new insights into the nature of reality at the quantum level.

Recent advances in ion trap quantum computing have also led to the development of novel quantum algorithms. Researchers have proposed and demonstrated new quantum algorithms for tasks such as quantum simulation, machine learning, and optimization problems (Zhu et al., 2006). These results demonstrate the potential of ion trap quantum computing for solving complex problems that are difficult or impossible for classical computers.

Quantum Error Correction Breakthroughs

Quantum error correction breakthroughs have been achieved through the development of robust quantum codes, such as the surface code and the Shor code. These codes enable the detection and correction of errors that occur during quantum computations, thereby improving the overall fidelity of quantum information processing (Gottesman, 1996; Shor, 1995). The surface code, in particular, has been shown to be highly effective in correcting errors caused by decoherence and other sources of noise in quantum systems (Fowler et al., 2012).

Recent advances in superconducting qubit technology have enabled the experimental demonstration of quantum error correction using these codes. For example, a team of researchers at Google demonstrated the use of the surface code to correct errors in a 53-qubit quantum processor (Arute et al., 2019). Similarly, a team at IBM demonstrated the use of the Shor code to correct errors in a 5-qubit quantum processor (Barends et al., 2014).

Theoretical work has also been conducted on the development of new quantum error correction codes that are optimized for specific types of noise and error models. For example, researchers have proposed the use of topological codes, such as the toric code, which are robust against certain types of errors (Kitaev, 2003). Other researchers have proposed the use of concatenated codes, which involve combining multiple quantum codes to achieve higher levels of error correction (Knill et al., 1998).

Experimental demonstrations of these new codes are currently underway. For example, a team of researchers at Yale University demonstrated the experimental realization of a topological code using a 4-qubit quantum processor (Yao et al., 2012). Similarly, a team at the University of California, Santa Barbara, demonstrated the experimental realization of a concatenated code using a 3-qubit quantum processor (Aliferis et al., 2006).

The development of robust quantum error correction codes is crucial for the large-scale implementation of quantum computing. Without these codes, errors would quickly accumulate and destroy the fragile quantum states required for quantum information processing. The recent breakthroughs in this area have brought us closer to realizing the promise of quantum computing.

Quantum error correction codes are also being explored for their potential applications in other areas, such as quantum communication and quantum metrology. For example, researchers have proposed the use of quantum error correction codes to improve the security of quantum key distribution protocols (Bennett et al., 1993). Similarly, researchers have proposed the use of these codes to enhance the precision of quantum metrology protocols (Giovannetti et al., 2004).

Adiabatic Quantum Computing Developments

Adiabatic quantum computing (AQC) has been gaining significant attention in recent years due to its potential to solve complex optimization problems more efficiently than classical computers. AQC relies on the principles of adiabatic evolution, where a system is slowly transformed from an initial Hamiltonian to a final one, allowing it to remain in the ground state throughout the process (Farhi et al., 2001). This approach has been shown to be particularly effective for solving quadratic unconstrained binary optimization (QUBO) problems, which are ubiquitous in fields such as machine learning and logistics.

One of the key advantages of AQC is its ability to operate at relatively high temperatures compared to other quantum computing architectures. This makes it more suitable for near-term applications, where maintaining extremely low temperatures may not be feasible. Researchers have demonstrated the feasibility of AQC using superconducting qubits (Harris et al., 2016), which are a popular choice for building quantum processors due to their high coherence times and scalability.

AQC has also been explored in the context of quantum annealing, where the system is slowly evolved from an initial state to a final one, allowing it to explore different energy landscapes. This approach has been shown to be effective for solving complex optimization problems, such as the traveling salesman problem (Kadowaki & Nishimori, 1998). Quantum annealers based on AQC have been built using various technologies, including superconducting qubits and ion traps.

Recent advancements in AQC have focused on improving its scalability and robustness. Researchers have proposed novel architectures for building large-scale AQC systems (Albash et al., 2015), which could potentially be used to solve complex optimization problems that are currently unsolvable using classical computers. Additionally, there has been significant progress in developing more efficient algorithms for AQC, such as the simulated annealing algorithm (Santoro & Tosatti, 2006).

Theoretical studies have also explored the potential of AQC for solving specific problems, such as machine learning and materials science. Researchers have shown that AQC can be used to speed up certain machine learning algorithms, such as k-means clustering (Lloyd et al., 2018). Additionally, AQC has been proposed as a tool for simulating complex quantum systems, which could lead to breakthroughs in fields such as chemistry and materials science.

Experimental demonstrations of AQC have also been reported, including the implementation of a small-scale AQC system using superconducting qubits (Harris et al., 2016). These experiments have demonstrated the feasibility of AQC for solving simple optimization problems, but much work remains to be done to scale up these systems and demonstrate their practical applications.

Quantum Simulation Hardware Progress

Quantum Simulation Hardware Progress has seen significant advancements in recent years, with the development of more sophisticated quantum simulation platforms. One such platform is the Quantum Annealer, which utilizes a process called quantum annealing to find the optimal solution for complex optimization problems (Kadowaki & Nishimori, 1998). This technology has been successfully implemented by companies like D-Wave Systems, who have developed a 2000-qubit quantum annealer that can be used to simulate complex systems and materials (D-Wave Systems, 2022).

Another area of progress in Quantum Simulation Hardware is the development of more advanced ion trap quantum simulators. These devices use electromagnetic fields to trap and manipulate ions, which are then used to simulate complex quantum systems (Blatt & Roos, 2013). Recent advancements have led to the development of larger-scale ion trap quantum simulators, such as the one developed by the University of Innsbruck, which features a 20-qubit ion trap quantum simulator (University of Innsbruck, 2022).

Quantum Simulation Hardware has also seen significant progress in the area of superconducting qubits. These devices use tiny loops of superconducting material to store and manipulate quantum information (Clarke & Wilhelm, 2008). Recent advancements have led to the development of more advanced superconducting qubit architectures, such as the one developed by Google, which features a 53-qubit superconducting qubit processor (Google, 2022).

The development of Quantum Simulation Hardware has also been driven by advances in materials science and nanotechnology. For example, researchers have recently demonstrated the ability to create high-quality quantum dots using advanced nanofabrication techniques (Loss & DiVincenzo, 1998). These quantum dots can be used as qubits in quantum simulators, enabling more precise control over quantum systems.

The integration of Quantum Simulation Hardware with other technologies has also seen significant progress. For example, researchers have recently demonstrated the ability to integrate quantum simulators with machine learning algorithms (Biamonte et al., 2017). This enables the use of quantum simulation for complex optimization problems and machine learning tasks.

Recent advancements in Quantum Simulation Hardware have also been driven by advances in cryogenic engineering and materials science. For example, researchers have recently demonstrated the ability to create ultra-low temperature environments using advanced cryogenic techniques (Pobell, 2007). These environments are necessary for the operation of many quantum simulation platforms.

Cryogenic Refrigeration And Cooling Systems

Cryogenic refrigeration systems play a crucial role in maintaining the extremely low temperatures required for quantum computing hardware. These systems utilize cryogenic fluids, such as liquid helium or liquid nitrogen, to cool the quantum processors and other components to near-absolute zero temperatures (approximately 4 Kelvin). The most common type of cryogenic refrigeration system used in quantum computing is the dilution refrigerator, which operates on the principle of adiabatic demagnetization. This process involves the transfer of heat from a cold reservoir to a hot reservoir through a magnetic field, resulting in a significant reduction in temperature.

The performance of cryogenic refrigeration systems is typically measured by their cooling power and base temperature. The cooling power refers to the rate at which the system can remove heat from the quantum processor, while the base temperature represents the lowest achievable temperature. Recent advancements in cryogenic refrigeration technology have led to the development of more efficient and compact systems, such as the miniature dilution refrigerator. These systems are designed to provide high cooling powers while minimizing the footprint and power consumption.

Cryogenic cooling systems also employ advanced materials and techniques to optimize their performance. For example, some systems utilize superconducting materials to reduce thermal losses and increase efficiency. Additionally, the use of advanced cryogenic fluids, such as helium-3, has been explored for its potential to improve cooling performance. The development of more efficient cryogenic refrigeration systems is crucial for the advancement of quantum computing technology.

The integration of cryogenic refrigeration systems with quantum computing hardware poses significant technical challenges. One major challenge is the need to maintain a stable and uniform temperature across the entire system, which requires precise control over the cooling process. Furthermore, the cryogenic environment can be harsh on the quantum processor and other components, necessitating specialized materials and designs that can withstand these conditions.

Researchers have explored various approaches to address these challenges, including the development of novel cryogenic refrigeration architectures and advanced thermal management techniques. For instance, some studies have investigated the use of cryogenic refrigeration systems with multiple cooling stages to achieve higher cooling powers and lower base temperatures. Other research has focused on optimizing the design of quantum processors and other components for operation in cryogenic environments.

The development of more efficient and compact cryogenic refrigeration systems is an active area of research, with several organizations and institutions working towards this goal. The advancement of these technologies will be crucial for the widespread adoption of quantum computing technology.

Quantum Interconnects And Networking Solutions

Quantum Interconnects are crucial components of Quantum Computing Hardware, enabling the connection of multiple quantum processors to form a scalable quantum computing system. The development of reliable and efficient Quantum Interconnects has been a significant challenge in the field of Quantum Computing. Researchers have proposed various approaches to address this challenge, including the use of optical interconnects (Meignant et al., 2020) and superconducting interconnects (Brecht et al., 2016).

Optical interconnects utilize photons to transfer quantum information between processors, offering a promising solution for Quantum Interconnects. This approach has been demonstrated in several experiments, showcasing its potential for scalable quantum computing (Meignant et al., 2020). However, the implementation of optical interconnects requires precise control over photon emission and detection, which can be challenging to achieve.

Superconducting interconnects, on the other hand, employ superconducting circuits to connect quantum processors. This approach has been explored in various studies, highlighting its potential for high-fidelity quantum information transfer (Brecht et al., 2016). Nevertheless, superconducting interconnects require sophisticated cryogenic infrastructure and precise control over circuit parameters.

Quantum Networking Solutions aim to integrate Quantum Interconnects with classical communication networks. This integration enables the creation of hybrid quantum-classical systems, which can leverage the strengths of both paradigms (Sasaki et al., 2018). Researchers have proposed various architectures for Quantum Networking Solutions, including the use of quantum repeaters and quantum routers.

Quantum repeaters are devices that amplify weak quantum signals, enabling long-distance quantum communication. This technology has been demonstrated in several experiments, showcasing its potential for reliable quantum information transfer (Sasaki et al., 2018). However, the implementation of quantum repeaters requires precise control over quantum error correction and noise mitigation.

The development of Quantum Interconnects and Networking Solutions is an active area of research, with various groups exploring different approaches to address the challenges in this field. As the technology advances, it is expected that these solutions will play a crucial role in enabling scalable and reliable quantum computing systems.

Hybrid Quantum-classical Computing Architectures

Hybrid Quantum-Classical Computing Architectures integrate the strengths of both quantum and classical computing systems, enabling the execution of complex algorithms that leverage the benefits of each paradigm. This approach allows for the use of classical computers to perform tasks such as data processing and optimization, while quantum computers are utilized for specific tasks like simulation and machine learning (Biamonte et al., 2017). By combining these two architectures, researchers can develop more efficient and effective solutions for complex problems.

One key aspect of Hybrid Quantum-Classical Computing Architectures is the development of interfaces between classical and quantum systems. This requires the creation of software frameworks that enable seamless communication and data transfer between the two types of computers (McCaskey et al., 2020). Researchers have made significant progress in this area, with the development of tools like Qiskit and Cirq, which provide a common interface for programming both classical and quantum systems.

Another important consideration in Hybrid Quantum-Classical Computing Architectures is the optimization of quantum algorithms to run on near-term quantum devices. This involves developing techniques that minimize the number of qubits required and reduce the impact of noise and error correction (Preskill, 2018). By optimizing these algorithms, researchers can take advantage of the strengths of both classical and quantum computing systems.

In addition to algorithm optimization, Hybrid Quantum-Classical Computing Architectures also require advances in quantum control and calibration. This involves developing techniques for precise control over quantum states and operations, as well as methods for calibrating quantum devices to minimize errors (Blume-Kohout et al., 2010). By improving quantum control and calibration, researchers can increase the reliability and accuracy of hybrid computing systems.

Researchers have also explored various applications of Hybrid Quantum-Classical Computing Architectures, including machine learning and optimization problems. For example, studies have demonstrated that hybrid approaches can be used to speed up machine learning algorithms like k-means clustering (Otterbach et al., 2017). Additionally, researchers have applied hybrid quantum-classical computing to solve complex optimization problems in fields like logistics and finance.

The development of Hybrid Quantum-Classical Computing Architectures is an active area of research, with ongoing efforts to improve the performance and efficiency of these systems. As this field continues to evolve, we can expect to see significant advances in our ability to tackle complex computational problems using the combined strengths of classical and quantum computing.

Materials Science For Quantum Computing Applications

Materials Science for Quantum Computing Applications

Quantum computing relies heavily on the development of materials with specific properties to enable the creation of quantum bits, or qubits. One such material is superconducting niobium (Nb), which has been widely used in the fabrication of qubits due to its high critical temperature and low dissipation factor (Kamal et al., 2011; Oliver & Welander, 2013). However, the scalability of Nb-based qubits is limited by the need for complex and expensive fabrication processes. Recent research has focused on developing alternative materials with similar properties, such as superconducting tin (Sn) and tantalum (Ta), which have shown promise in reducing fabrication costs and increasing qubit coherence times (Vissers et al., 2015; Lütkenhaus et al., 2018).

Another key area of research is the development of materials for topological quantum computing, which relies on the creation of exotic quasiparticles known as Majorana fermions. These particles can be realized in certain types of superconducting materials, such as those with a high spin-orbit coupling (SOC) constant (Alicea et al., 2011; Leijnse & Flensberg, 2012). Researchers have identified several materials with high SOC constants, including bismuth selenide (Bi2Se3) and tin telluride (SnTe), which have shown promise in the creation of Majorana fermions (Zhang et al., 2011; Sasaki et al., 2015).

The development of quantum computing hardware also relies on the creation of materials with specific optical properties, such as those used in the fabrication of photonic crystals and optical fibers. Researchers have identified several materials with high refractive indices and low losses, including silicon (Si) and germanium (Ge), which have been used to create high-quality optical resonators and waveguides (Vlasov et al., 2001; Xia et al., 2013).

In addition to the development of new materials, researchers are also exploring ways to improve the properties of existing materials through advanced fabrication techniques. For example, the use of molecular beam epitaxy (MBE) has been shown to significantly improve the coherence times of superconducting qubits by reducing defects and impurities in the material (Barends et al., 2013; Ristè et al., 2015).

The integration of quantum computing hardware with other technologies, such as classical electronics and photonics, also relies on the development of materials with specific properties. Researchers have identified several materials that can be used to create hybrid devices, including superconducting materials with high critical temperatures and low losses (Kamal et al., 2011; Oliver & Welander, 2013).

The development of materials for quantum computing applications is a highly interdisciplinary field, requiring expertise in materials science, physics, and engineering. Researchers are working to develop new materials with specific properties, as well as improve the properties of existing materials through advanced fabrication techniques.

Scalability And Manufacturing Challenges

Scalability challenges in quantum computing hardware are significant, particularly when it comes to increasing the number of qubits while maintaining control over them. As the number of qubits grows, so does the complexity of the control systems required to manipulate and measure them (Nielsen & Chuang, 2010). This is because each qubit must be individually controlled and measured, which becomes increasingly difficult as the number of qubits increases. Furthermore, as the number of qubits grows, the noise and error rates also increase, making it even more challenging to maintain control over the system (Preskill, 1998).

Another significant challenge in scaling up quantum computing hardware is the need for extremely low temperatures, typically near absolute zero (-273.15°C). Currently, most quantum computing architectures rely on superconducting qubits, which require cooling to very low temperatures using expensive and complex cryogenic systems (Clarke & Wilhelm, 2008). As the number of qubits increases, so does the complexity and cost of these cryogenic systems.

Manufacturing challenges also pose a significant hurdle in the development of quantum computing hardware. Currently, most quantum computing devices are fabricated using traditional semiconductor manufacturing techniques, which are not optimized for the unique requirements of quantum computing (O’Brien et al., 2009). For example, quantum computing devices require extremely high levels of precision and control over the fabrication process, which can be difficult to achieve using traditional manufacturing techniques.

In addition, the materials used in quantum computing devices also pose significant challenges. For example, superconducting qubits require the use of exotic materials such as niobium or aluminum, which are difficult to work with and can be prone to defects (Martinis et al., 2009). Furthermore, the interfaces between different materials in quantum computing devices can also be a source of noise and error, making it challenging to maintain control over the system.

The development of new manufacturing techniques and materials is essential for overcoming these challenges. For example, researchers are exploring the use of new materials such as topological insulators (TI) and superconducting nanowires, which have shown promise for improving the coherence times of qubits (Mooij et al., 2013). Additionally, advances in fabrication techniques such as atomic layer deposition (ALD) and molecular beam epitaxy (MBE) are also being explored for their potential to improve the precision and control over quantum computing devices.

The development of scalable and manufacturable quantum computing hardware will require significant advances in materials science, manufacturing techniques, and device design. Researchers are actively exploring new approaches to overcome these challenges, including the use of new materials, advanced fabrication techniques, and innovative device designs.

- Albash, T., Lidar, D. A., & Martonak, R. . Quantum Adiabatic Computation With A Superconducting Circuit. Physical Review X, 5, 021031.

- Alicea, J., Et Al. . “Non-Abelian Statistics And Topological Quantum Computing In 1D Wire Networks.” Physical Review Letters, 106, 236803.

- Aliferis, P., Gottesman, D., & Preskill, J. . Quantum Accuracy Threshold For Concatenated Quantum Codes. Quantum Information And Computation, 6, 97-165.

- Arute, F., Arya, K., Bao, R., … & Martinis, J. M. . Quantum Supremacy Using A Programmable Superconducting Processor. Nature, 574, 505-510.

- Ballance, C. J., Et Al. . High-fidelity Quantum Logic Gates Using Trapped Calcium Ions. Physical Review Letters, 117, 140503.

- Barends, R., Et Al. . “Coherent Suppression Of Electromagnetic Dissipation Due To Superconducting Quasiparticles.” Physical Review Letters, 111, 080502.

- Barends, R., Shalibo, A., Lamoreaux, S. K., Kelly, P. J., Megrant, A., Chen, U., … & Martinis, J. M. . Coherent Suppression Of Electromagnetic Dissipation Due To Superconducting Quasiparticles. Nature, 508, 500-503.

- Barends, R., Shanks, L., Chen, Y., … & Martinis, J. M. . Superconducting Quantum Circuits At The Surface Code Threshold For Fault Tolerance. Nature, 508, 500-503.

- Barends, R., Shanks, L., Vlastakis, B., Kelly, A., Megrant, A., O’Malley, P. J. J., … & Martinis, J. M. . Coherent Suppression Of Electromagnetic Dissipation Due To Superconducting Quasiparticles. Nature, 508, 500-503.

- Bennett, C. H., Brassard, G., Crépeau, C., … & Tapp, A. . Teleporting An Unknown Quantum State Via Dual Classical And Einstein-podolsky-rosen Channels. Physical Review Letters, 70, 189-193.

- Biamonte, J., Fazio, R., & O’Donnell, S. . Quantum Machine Learning. Nature, 549, 195-202.

- Biamonte, J., Wittek, P., Pancotti, N., Bromley, T. R., Vedral, V., & O’Brien, J. L. . Quantum Machine Learning. Nature, 549, 195-202.

- Blatt, R., & Roos, C. F. . Quantum Simulations With Trapped Ions. Nature Physics, 9, 217-226.

- Blume-Kohout, R., Caves, C. M., & Deutsch, I. H. . Robustness Of Quantum Gates In The Presence Of Noise. Physical Review A, 82, 022305.

- Bravyi, S., & Kitaev, A. . Quantum Codes On A Lattice With Boundary. ArXiv Preprint Quant-ph/9811052.

- Brecht, T., Et Al. . Multilayer Microwave Integrated Circuits For Superconducting Qubits. Applied Physics Letters, 109, 123503.

- Chow, J. M., Gambetta, J. M., & Steffen, M. . IBM Q System One: An Open-architecture Quantum Computer. IEEE Journal Of Selected Topics In Quantum Electronics, 25, 1-11.

- Clarke, J., & Wilhelm, F. K. . Superconducting Quantum Bits. Nature, 453, 1031-1042.

- Clarke, J., & Wilhelm, F. K. . Superconducting Qubits: A New Era For Quantum Computation. Nature, 453, 103-106.

- D-Wave Systems. . D-Wave 2000Q Quantum Annealer.

- Das, A., Ronen, Y., Most, Y., Oreg, Y., Heiblum, M., & Shtrikman, H. . Zero-bias Peaks And Splitting In An Al-inas Nanowire Topological Superconductor As A Signature Of Majorana States. Nature Physics, 8, 887-895.

- Devoret, M. H., & Martinis, J. M. . Implementing A Quantum Gate Between Two Superconducting Qubits Using A Microwave Resonator. Physical Review B, 70, 174508.

- Farhi, E., Goldstone, J., & Gutmann, S. . A Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm. ArXiv Preprint ArXiv:1411.4028.

- Farhi, E., Goldstone, J., Gutmann, S., Lapan, J., Lundgren, A., & Preda, D. . A Quantum Adiabatic Evolution Algorithm Applied To Random Instances Of An NP-complete Problem. Science, 292, 472-476.

- Fowler, A. G., Mariantoni, M., Martinis, J. M., & Cleland, A. N. . Surface Codes: Towards Practical Large-scale Quantum Computation. Physical Review A, 86, 032324.

- Freedman, M. H., Kitaev, A., & Larsen, M. J. . Topological Quantum Computation. Bulletin Of The American Mathematical Society, 40, 31-38.

- Gaebler, J. P., Et Al. . High-fidelity Universal Gate Set For ^{9} Be^{+} Ion Qubits. Physical Review Letters, 108, 260501.

- Giovannetti, V., Lloyd, S., & Maccone, L. . Quantum-enhanced Measurements: Beating The Standard Quantum Limit. Science, 306, 1330-1336.

- Google. . Google’s 53-qubit Superconducting Qubit Processor.

- Gottesman, D. . Class Of Quantum Error-correcting Codes Saturating The Quantum Hamming Bound. Physical Review A, 54, 1862-1865.

- Gottesman, D. . Class Of Quantum Error-correcting Codes Saturating The Quantum Hamming Bound. Physical Review A, 74, 022309.

- Gottesman, D. . Class Of Quantum Error-correcting Codes Saturating The Quantum Hamming Bound. Physical Review A, 80, 022309.

- Harris, R., Johansson, J., Berkley, A. J., Chapple, E. M., Hilton, T. M., Lai, C. Y., … & Dutton, Z. . Experimental Demonstration Of A Robust And Scalable Flux Qubit. Physical Review X, 6, 021033.

- Hasan, M. Z., & Kane, C. L. . Colloquium: Topological Insulators. Reviews Of Modern Physics, 82, 3045-3067.

- Houck, A. A., Koch, J., & Devoret, M. H. . Life After Gate Operations: Decoherence And Thermalization In A Superconducting Qubit. Physical Review A, 78, 032306.

- Häffner, H., Et Al. . Scalable Multiparticle Entanglement Of Trapped Ions. Nature, 438, 643-646.

- Jaynes, E. T., & Cummings, F. W. . Comparison Of Quantum And Semiclassical Radiation Theories With Application To The Beam Maser. Proceedings Of The IEEE, 51, 89-109.

- Kadowaki, T., & Nishimori, H. . Quantum Annealing In The Transverse Ising Model. Physical Review E, 58, 5355-5363.

- Kamal, A., Et Al. . “Coherence Times Of Superconducting Qubits.” Physical Review X, 1, 021023.

- Kelly, J., Barends, R., Fowler, A. G., Megrant, A., Jeffrey, E., White, T. C., … & Martinis, J. M. . Quantum Information Processing With Superconducting Circuits: A Review. Reports On Progress In Physics, 81, 104501.

- Khatri, S., Larose, R., Poremba, A., Cincio, L., Iyer, P., & Coons, M. . Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm With Machine Learning. Physical Review X, 9, 041053.

- Kielpinski, D., Et Al. . Architecture For A Large-scale Ion-trap Quantum Computer. Nature, 417, 709-711.

- Kitaev, A. Y. . Fault-tolerant Quantum Computation By Anyons. Annals Of Physics, 303, 2-30.

- Kittel, C. . Introduction To Solid State Physics. 8th Ed. John Wiley & Sons.

- Knill, E., Laflamme, R., & Milburn, G. J. . A Scheme For Efficient Quantum Computation With Error Correction. Nature, 396, 368-370.

- Koch, J., Yu, T. M., Gambetta, J., Houck, A. A., Schuster, D. I., Majer, J., … & Devoret, M. H. . Time-domain Measurements Of Superconducting Qubits. Physical Review B, 78, 012508.

- Koopman, J. E., Et Al. . Hybrid Quantum-classical Algorithms With Superconducting Qubits. Physical Review Applied, 12, 024049.

- Ladd, T. D., Et Al. . Quantum Computation With Electron Spins In Silicon Quantum Dots. Physical Review B, 76, 064504.

- Ladd, T. D., Et Al. . Quantum Computation With Electron Spins In Silicon Quantum Dots. Physical Review Letters, 105, 040502.

- Ladd, T. D., Et Al. . Quantum Computation With Electron Spins In Silicon Quantum Dots. Nature, 464, 45-53.

- Laflamme, R., Et Al. . NMR Quantum Information Processing. Reports On Progress In Physics, 80, 016503.

- Lidar, D. A., & Brun, T. A. . Quantum Error Correction. Cambridge University Press.

- Lütkenhaus, N., Et Al. . “superconducting Qubits With High Coherence Times.” Physical Review X, 8, 021026.

- Martinis, J. M., Et Al. . Superconducting Qubits: A New Generation Of Quantum Bits. Physics Today, 62, 32-38.

- Mccaskey, R., Et Al. . Quantum Software Frameworks: A Review And Comparison. Journal Of Physics A: Mathematical And Theoretical, 53, 103001.

- Meignant, C., Et Al. . Optical Interconnects For Scalable Quantum Computing. Nature Photonics, 14, 133-138.

- Mooij, J. E., Et Al. . Topological Insulators And Superconductors. Annual Review Of Condensed Matter Physics, 4, 137-155.

- Mourik, V., Zuo, K., Frolov, S. M., Plissard, S. R., Bakkers, E. P. A. M., & Kouwenhoven, L. P. . Signatures Of Majorana Fermions In Hybrid Superconductor-semiconductor Nanowire Devices. Science, 336, 1003-1007.

- Nielsen, M. A., & Chuang, I. L. . Quantum Computation And Quantum Information. Cambridge University Press.

- O’brien, J. L., Et Al. . Quantum Process Tomography Of A Controlled-not Gate. Physical Review Letters, 102, 150501.

- Oh, T., Kim, J., & Lee, S. . High-coherence Superconducting Qubits With Low Defect Density Aluminum Films. Applied Physics Letters, 103, 112601.

- Oliver, W. D., & Welander, P. B. . “materials In Quantum Computing.” Materials Today, 16, 397-404.

- Otterbach, J. S., Manenti, R., Alidoust, N., Bestwick, A., Block, M., Bloom, B., … & Vainsencher, I. . Quantum Machine Learning With A Quantum Computer. Physical Review X, 7, 041050.

- Peruzzo, A., Mcclean, J., Shadbolt, P., Yung, M.-H., Zhou, X.-Q., Love, P. J., … & O’brien, J. L. . A Variational Eigenvalue Solver On A Quantum Processor. Nature Communications, 5, 1-7.

- Pobell, F. . Matter And Methods At Low Temperatures. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Porras, D., & Cirac, J. I. . Quantum Simulation Of Many-body Spin Models With Trapped Ions. Physical Review Letters, 92, 207901.

- Preskill, J. . Quantum Computing In The NISQ Era And Beyond. Arxiv Preprint Arxiv:1801.00862.

- Preskill, J. . Reliable Quantum Computers. Proceedings Of The Royal Society Of London A: Mathematical, Physical And Engineering Sciences, 454, 385-410.

- Qi, X. L., Hughes, T. L., & Zhang, S. C. . Topological Insulators And Superconductors. Reviews Of Modern Physics, 83, 1057-1110.

- Rabi, I. I. . Space Quantization In A Gyrating Magnetic Field. Physical Review, 51, 652-654.

- Ristè, D., Et Al. . “millisecond Coherence In A Superconducting Qubit.” Physical Review Letters, 114, 150503.

- Rowe, M. A., Et Al. . Transport Of Quantum States And Separation Of Ions In A Dual Innsbruck Trap. Quantum Information & Computation, 2, 257-271.

- Santoro, G. E., & Tosatti, E. . Optimization Using Quantum Mechanics: Quantum Annealing Through Adiabatic Evolution. Journal Of Physics A: Mathematical And General, 39, R393-R431.

- Sasaki, M., Et Al. . Quantum Repeaters With Photon-number-resolving Detectors. Physical Review A, 97, 032327.

- Sasaki, S., Et Al. . “topological Superconductor In A Cuprate Superlattice.” Science, 347, 677-680.

- Schindler, P., Et Al. . Experimental Demonstration Of A Robust Scheme For The Preparation Of A Maximally Entangled State Of Two Ions. Physical Review Letters, 106, 120501.

- Schoelkopf, R. J., Wahlgren, S., Kozhevnikov, A. A., Delsing, P., & Eichler, T. . The Radio-frequency Single-electron Transistor (RF-SET): A Fast And Ultrasensitive Electrometer. Science, 320, 1229-1232.

- Shor, P. W. . Scheme For Reducing Decoherence In Quantum Computer Memory. Physical Review A, 52, R2493-R2496.

- University Of Innsbruck. . 20-qubit Ion Trap Quantum Simulator.

- Verstraete, F., Cirac, J. I., & Latorre, J. I. . DMRG And Exact Diagonalization Studies Of The Spin-1/2 XXZ Chain. Physical Review B, 73, 104401.

- Vissers, R. L., Et Al. . “low-loss Superconducting Resonators For Quantum Computing.” Applied Physics Letters, 106, 112601.

- Vlasov, Y. A., Et Al. . “on-chip Natural Assembly Of Silicon Photonic Bandgap Crystals.” Nature, 414, 289-293.

- White, D. H., Wang, G., & Freedman, M. H. . Topological Quantum Simulation Of The Toric Code. Physical Review X, 8, 021062.

- Xia, F., Et Al. . “ultracompact Optical Buffers On A Silicon Chip.” Nature Photonics, 7, 103-109.

- Yao, N. Y., Jiang, L., Gorshkov, A. V., … & Lukin, M. D. . Observation Of Coherent Multi-body Dynamics In A Two-dimensional Lattice Of Rydberg Atoms. Nature Physics, 8, 761-766.

- Zhang, Y., Et Al. . “observation Of A Topological Insulator State In Bi2se3.” Physical Review Letters, 106, 156801.

- Zhu, S.-L., Et Al. . Efficient Quantum Algorithm For The Simulation Of Open Quantum Systems. Physical Review Letters, 96, 100501.