The double-slit experiment is a pivotal demonstration of quantum mechanics, illustrating the wave-particle duality inherent in quantum theory. First performed by Thomas Young in 1803 with light, the experiment revealed an interference pattern typical of waves. When repeated with electrons, it showed that particles like electrons exhibit wavelike behavior when unobserved. This phenomenon challenges classical notions of reality, as particles appear to exist in multiple states simultaneously until measured.

The act of observation fundamentally alters particle behavior, transitioning from a wavelike interference pattern to a particle distribution. This paradox is encapsulated in the Copenhagen interpretation, which posits that quantum systems do not possess definite properties until measured. The experiment also highlights the nonlocal nature of quantum mechanics, suggesting that particles somehow know about both slits simultaneously, even when they appear to pass through one slit at a time.

The broader impact of the double-slit experiment extends beyond theoretical physics into practical applications and philosophical interpretations. It underscores the probabilistic nature of quantum mechanics, influencing technological advancements in quantum computing and cryptography. The principles observed in the experiment are foundational to quantum mechanics, particularly concepts like superposition and entanglement, which have been experimentally validated and continue to shape our understanding of reality.

Young’s Original Discovery With Light

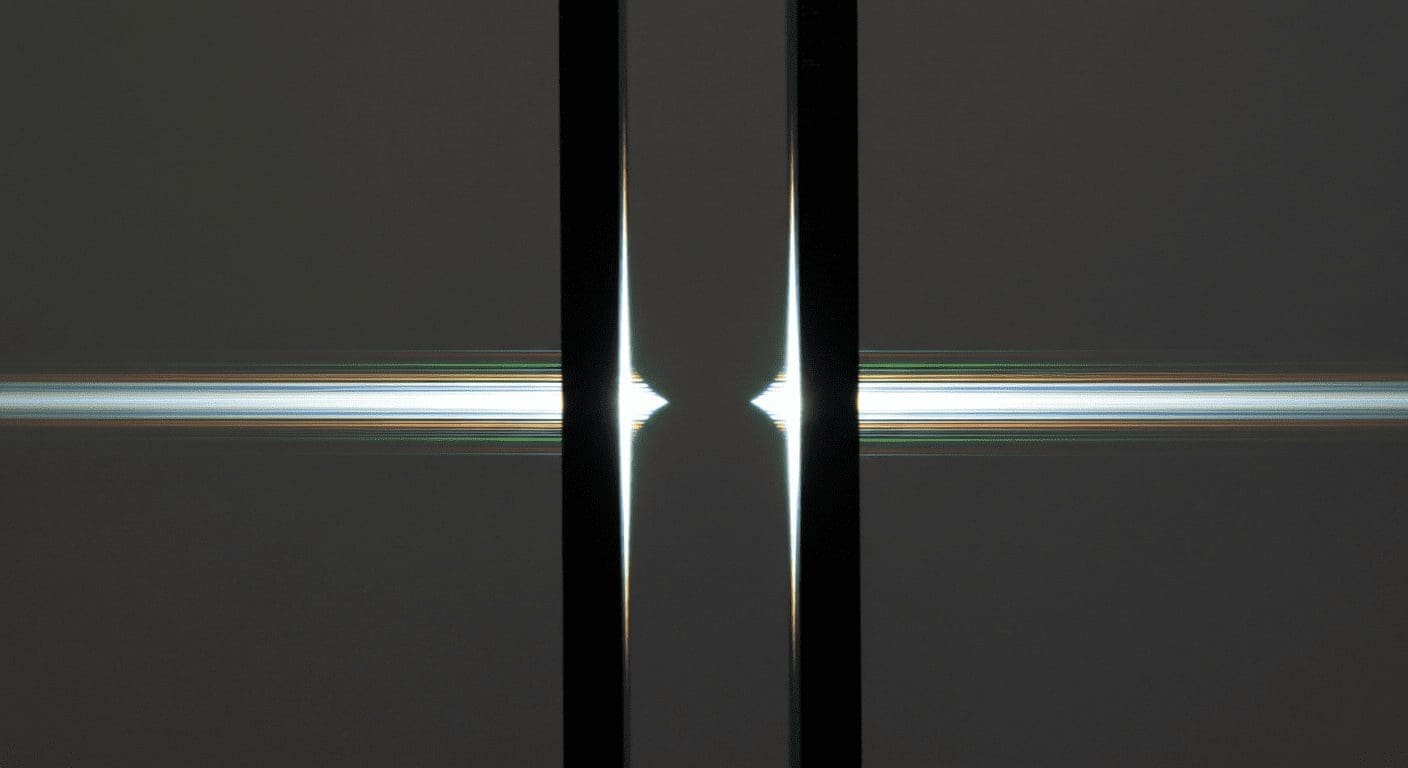

The double-slit experiment, first conducted by Thomas Young in 1803, demonstrated that light exhibits wave-like behavior. When light passes through two slits, it creates an interference pattern on a screen, characterized by alternating bright and dark bands. This observation was pivotal in supporting the wave theory of light over the particle theory prevalent at the time. Young’s experiment provided compelling evidence for the wave nature of light, as the interference pattern could only be explained by waves interfering with each other.

In the 20th century, the double-slit experiment was revisited using electrons, revealing a startling quantum phenomenon. When electrons were fired one at a time through the slits, they still produced an interference pattern, suggesting that particles exhibit wave-like properties. This discovery led to the concept of wave-particle duality, where quantum entities can behave as both waves and particles depending on the experimental setup. The quantum version of the experiment demonstrated that even single particles could interfere with themselves, challenging classical notions of particle behavior.

The significance of the double-slit experiment lies in its profound implications for our understanding of reality at the quantum level. It highlights the probabilistic nature of quantum mechanics, where particles do not have definite positions until measured. This experiment has been instrumental in shaping interpretations of quantum theory, such as the Copenhagen interpretation and the pilot-wave theory, each offering different explanations for the observed phenomena.

The experiment’s influence extends beyond quantum mechanics into broader scientific discourse. It underscores the importance of experimental evidence in challenging existing paradigms and driving theoretical advancements. The double-slit experiment remains a cornerstone in physics education, illustrating fundamental principles of wave-particle duality and the probabilistic nature of quantum systems.

The Quantum Revolution It Sparked

The Double-Slit Experiment is a pivotal demonstration in quantum physics that reveals the wave-particle duality of matter and light. Conducted initially by Thomas Young in 1803 using light, the experiment showed an interference pattern when light passed through two slits, indicating wave-like behavior. Later, in the 20th century, similar experiments with electrons confirmed this dual nature, where particles also produced interference patterns, behaving like waves until observed.

This experiment challenges classical physics by showing that quantum entities can exhibit both wave and particle properties depending on measurement conditions. The observer effect is a key outcome: measuring which slit an electron passes through collapses the wave function, causing it to behave as a particle rather than a wave. This phenomenon underscores the fundamental role of observation in quantum mechanics.

These findings have profound implications. They led to the development of quantum mechanics and concepts like superposition and entanglement. Superposition allows particles to exist in multiple states simultaneously until measured, while entanglement connects particles across distances, influencing each other instantaneously.

Technological advancements such as semiconductors, MRI machines, and quantum computing rely on our understanding of wave-particle duality. Quantum computing, for instance, leverages superposition and entanglement to perform complex calculations more efficiently than classical computers.

The Double-Slit Experiment fundamentally altered our understanding of reality at the quantum level, highlighting that particles lack definite properties until measured. This insight drives technological innovation and theoretical exploration in fields like quantum cryptography and computing.

Electron And Molecule Versions Of The Experiment

The double-slit experiment has been pivotal in understanding wave-particle duality, particularly when applied to electrons and molecules. When electrons are fired at a screen with two slits, they produce an interference pattern indicative of waves. However, observing which slit each electron passes through collapses this pattern into one resembling particles. This phenomenon was first demonstrated with light, showing its dual nature, and later replicated with electrons, challenging classical notions of particle behavior.

Experiments using larger molecules, such as buckyballs and even more complex structures, have revealed similar interference patterns. These findings suggest that wave-like properties are not confined to microscopic particles but can extend to macroscopic objects under specific conditions. The ability of these molecules to exhibit both wave and particle characteristics underscores the universality of quantum principles across different scales.

The implications of these experiments are profound. They challenge our everyday perceptions of reality, where objects are neatly categorized as either waves or particles. Instead, quantum mechanics introduces a more nuanced view where entities can embody properties of both, depending on the context and observational setup. This has led to deeper explorations into the nature of matter and energy at fundamental levels.

Key references supporting these findings include works by Richard Feynman, who extensively discussed the double-slit experiment in his lectures on quantum electrodynamics. Additionally, studies published in reputable journals like Nature and Physical Review Letters detail experiments with larger molecules, confirming the persistence of wave-particle duality across various scales.

These experiments not only validate the principles of quantum mechanics but also pave the way for further research into the behavior of matter at different levels. They highlight the importance of experimental evidence in shaping our understanding of the physical world and underscore the need for continuous exploration to uncover the mysteries of quantum phenomena.

The Measurement Problem Explained

In the early 20th century, the double-slit experiment was revisited in the context of quantum mechanics. When electrons were used instead of light, the experiment revealed that particles also exhibit wave-like behavior, producing interference patterns similar to those observed with light. This discovery demonstrated the principle of wave-particle duality, where quantum entities can behave as both waves and particles depending on the experimental setup.

The double-slit experiment became a cornerstone in understanding the measurement problem in quantum mechanics. When detectors were placed at the slits to observe which slit the particle passed through, the interference pattern disappeared, and the particles behaved like classical objects, producing two distinct clusters of points corresponding to the slits. This result suggested that the act of measurement fundamentally alters the system, implying a deep connection between observation and the state of the system.

The experiment also highlighted the non-local nature of quantum mechanics. The interference pattern observed in the double-slit experiment could not be explained by classical locality, where effects are only produced by nearby causes. Instead, it implied that particles somehow “know” about both slits simultaneously, even when they appear to pass through one slit at a time.

The implications of the double-slit experiment have been extensively debated and analyzed in the context of various interpretations of quantum mechanics, such as the Copenhagen interpretation, pilot-wave theory, and many-worlds interpretation. Each interpretation attempts to explain the strange results of the experiment while adhering to the mathematical framework of quantum mechanics.

Quantum Eraser And Delayed Choice Variations

The Double-Slit Experiment is a cornerstone of quantum physics, illustrating the wave-particle duality of particles. When particles pass through two slits, they create an interference pattern characteristic of waves. However, measuring which slit each particle traverses collapses this pattern into two clusters, akin to classical particles.

The Quantum Eraser experiment extends this concept by erasing path information after the fact. By using entangled photons or similar methods, researchers can erase which slit a particle passed through, potentially restoring the interference pattern. This suggests that a particle’s behavior is influenced by future measurements, challenging classical notions of causality.

The Delayed Choice experiment introduces a temporal aspect, delaying the measurement decision until after the particle has passed through the slits. This setup tests whether the act of measurement affects the particle’s past state, implying that reality may not be predetermined but shaped by observation.

These experiments have been replicated and are widely accepted in the physics community as evidence supporting quantum mechanics. They challenge classical interpretations and suggest that reality is indeterminate until measured. While some propose alternative theories like many-worlds or pilot-wave theory, the consensus leans towards quantum mechanics’ explanations.

Feynman’s lectures highlight the experiment’s role in demonstrating quantum weirdness, emphasizing that no classical explanation suffices. Aspect’s experiments with entangled photons further support quantum mechanics by confirming Bell’s inequalities, reinforcing the non-local nature of quantum phenomena.

In conclusion, these experiments underscore the fundamental strangeness of quantum reality, where particles’ states are not fixed until measured, and future measurements can influence past outcomes, reshaping our understanding of causality and reality.

Implications For Modern Physics

The double-slit experiment stands as a cornerstone in the realm of quantum mechanics, illustrating the enigmatic wave-particle duality. Conducted initially by Thomas Young in 1803 with light, the experiment revealed an interference pattern characteristic of waves. Subsequent iterations using electrons corroborated this phenomenon, demonstrating that particles like electrons exhibit wave-like behavior when unobserved.

This experiment’s profound implication lies in its challenge to classical notions of reality. The act of observation fundamentally alters particle behavior, transitioning from a wave-like interference pattern to a particle distribution. This paradox is encapsulated in the Copenhagen interpretation, which posits that quantum systems do not possess definite properties until measured.

The principles observed in the double-slit experiment are foundational to quantum mechanics, particularly the concepts of superposition and entanglement. Superposition refers to a particle’s ability to exist in multiple states simultaneously, while entanglement describes particles’ interconnected states regardless of distance. These principles have been experimentally validated, notably in Aspect et al.’s 1982 work on quantum entanglement.

The double-slit experiment’s broader impact extends beyond theoretical physics into practical applications and philosophical interpretations. It underscores the probabilistic nature of quantum mechanics, influencing technological advancements such as quantum computing and cryptography. Moreover, it has sparked debates among physicists regarding the interpretation of quantum phenomena, with the Copenhagen interpretation being a focal point alongside other perspectives.

In summary, the double-slit experiment is pivotal in illustrating wave-particle duality and challenging classical physics. Its implications are integral to understanding quantum mechanics’ principles and have far-reaching effects on theoretical and applied sciences.