Some technology observers liken the quest for usable quantum computers to the pursuit of efficient energy production through nuclear fusion. Both technologies are ethereal in their make-up, and we can’t easily notice the physical processes. Do the similarities end there? Or is there some fundamental relatedness to these technologies? Both promise so much but are not seemingly here in any real capacity one could argue.

Energy consumption has been a fundamental driver of human development, with demand rising significantly throughout history as societies evolved. Population growth has influenced the trajectory of energy use. Technological advancements and economic development have also played a crucial role. These factors have fueled the demand for more efficient and abundant energy sources.

The Future of Quantum Computing

Below is a historical overview of the global energy demand from early human civilizations.

- Pre-Industrial Era (Before 1800)

Energy demand was low, relying primarily on biomass (wood, peat) for heating, cooking, and manual labor. Human and animal power were the primary sources of energy for agriculture and transportation. - Industrial Revolution (1800–1900)

The advent of the steam engine and mechanized industry led to a surge in energy demand, with coal becoming the dominant energy source. Population growth and urbanization increased significantly, further driving energy consumption. - Early 20th Century (1900–1950)

Oil and natural gas emerged as major energy sources, especially with the rise of automobiles and industrial expansion. Electricity grids expanded, and population growth continued to raise global energy demand. - Post-World War II Boom (1950–1970)

The global economy experienced rapid industrialization and urbanization, leading to a massive increase in energy consumption, driven primarily by oil. Nuclear power emerged as a new energy source, while coal and oil continued to dominate. - Oil Crises and Diversification (1970–1990)

The 1970s oil crises led to energy diversification, with increased reliance on natural gas, nuclear power, and early investments in renewable energy. Energy efficiency and alternative technologies became priorities, though fossil fuels still dominated. - Modern Era (1990–Present)

Energy demand surged, particularly in developing countries like China and India. Fossil fuels remain dominant, but significant growth of renewables (wind, solar) began to reshape the energy landscape. The push for decarbonization, sustainability, and investments in cleaner technologies intensified.

Nuclear Fusion, The Future Technology That Never Arrives?

Nuclear fusion has long been heralded as the ultimate clean energy solution, capable of revolutionizing the way we power our world. Often described as the “holy grail” of energy, fusion is the process that fuels the stars, including our own Sun.

Nuclear fission splits heavy atoms to release energy. Unlike this, nuclear fusion combines light atomic nuclei, typically hydrogen isotopes. It works under extreme conditions of heat and pressure. The result is a release of vast amounts of energy, far exceeding what current nuclear fission reactors can produce. Additionally, it does not generate any long-lived radioactive waste.

Fusion is appealing because of its potential to provide virtually limitless energy. It uses abundant fuels like deuterium, found in seawater, and tritium, which can be bred from lithium. Theoretically, a small amount of these elements could power entire cities for years. Yet, despite decades of research, achieving controlled nuclear fusion remains an immense scientific challenge. It also presents engineering challenges. The process requires temperatures that exceed 100 million degrees Celsius to initiate the reaction.

Recent breakthroughs are bringing fusion energy closer to reality. Companies and governments around the world are racing to develop practical fusion reactors. If successful, nuclear fusion could provide a sustainable and safe energy future, powering the planet with clean, inexhaustible energy.

Two light atomic nuclei combine to form a heavier nucleus during nuclear fusion, releasing immense energy. This is the fundamental reaction powering stars, including our Sun. The possibility of harnessing fusion on Earth for energy has captivated scientists for decades. Diving into the physics governing atomic interactions is essential to understand how fusion works. One must also explore the conditions required for fusion to occur. Finally, it is crucial to understand the mechanisms used to achieve these conditions in a controlled environment.

The Physics of Fusion

At the atomic level, nuclei consist of protons and neutrons. Because of the protons, they carry a positive charge. Like charges repel each other. The nuclei of atoms repel each other with significant force. This is a phenomenon known as the Coulomb barrier. Suppose these nuclei are brought close enough together. In that case, the “strong nuclear” force can take over. It is much more powerful than the electrostatic repulsion at short distances. This force can bind the nuclei together.

Fusion happens when two light nuclei collide at high speeds. These nuclei are typically isotopes of hydrogen, deuterium, and tritium. When they overcome the Coulomb barrier and fuse, they form a heavier nucleus, usually helium. This process releases energy in the form of high-speed neutrons. Energy is released in fusion because the mass of the final product is slightly less. It is less than the sum of the masses of the original nuclei. This “missing mass” is converted into energy according to Einstein’s famous equation, E = mc².

Current Nuclear Fusion Research

The economics of nuclear fusion are attractive to many countries. Harnessing atomic fusion means an almost limitless and cheap supply. It would likely radically change our human relationship with just about everything. As we can see, humans have put more extensive energy demands on the planet.

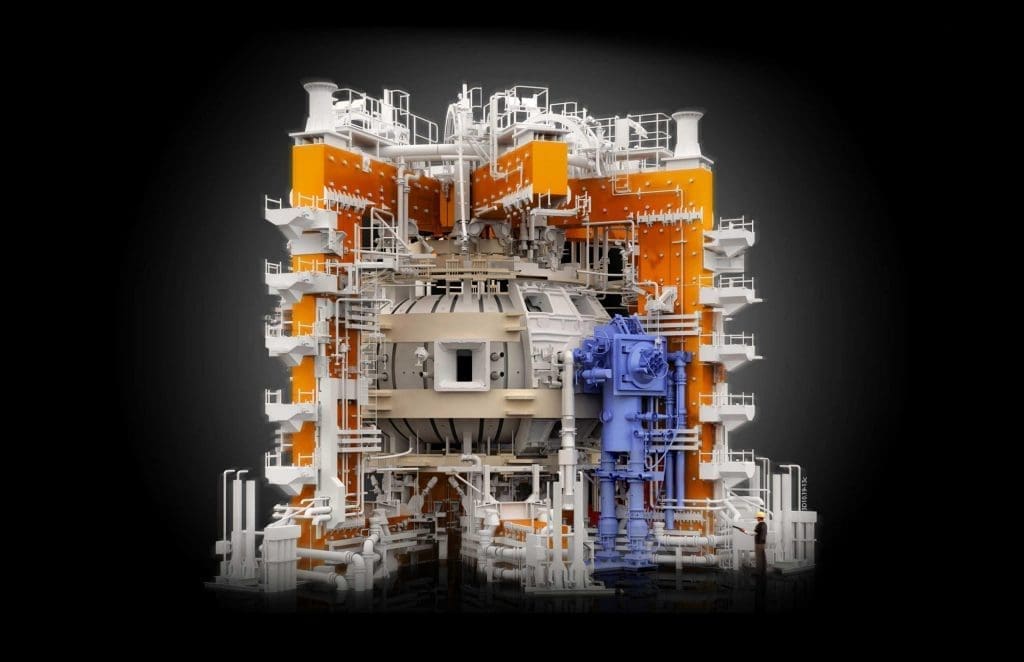

ITER (International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor)

ITER, based in southern France, is the world’s largest and most advanced fusion experiment. It uses the magnetic confinement technique through a tokamak reactor to show sustained fusion reactions that produce more energy than consumed.

ITER will use deuterium and tritium fuel, heated to 150 million degrees Celsius, in order to create fusion plasma. This international collaboration, involving 35 countries, is designed to pave the way for commercial fusion power plants.

ITER’s first plasma operation is expected in the early 2030s, and it is projected to generate 500 MW of fusion power from 50 MW of input energy.

National Ignition Facility (NIF)

The National Ignition Facility at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California is focused on inertial confinement fusion (ICF). NIF uses powerful lasers to compress and heat small deuterium-tritium fuel pellets to achieve the conditions necessary for fusion.

In 2022, NIF achieved a major milestone when it briefly produced more fusion energy than the energy delivered by the lasers, known as ignition. This marked a significant breakthrough in fusion research, though additional progress is needed to achieve sustained, practical energy production.

Joint European Torus (JET)

Located in the UK, the Joint European Torus (JET) is currently the largest operational fusion reactor and a key experimental facility for ITER. JET operates using magnetic confinement and achieved a record fusion energy output of 59 megajoules in 2021, using a deuterium-tritium fuel mix similar to what ITER will use.

JET is instrumental in testing plasma physics and materials under conditions close to those expected in ITER, helping refine fusion technologies for future reactors.

SPARC by Commonwealth Fusion Systems

Commonwealth Fusion Systems (CFS), a private company founded by MIT scientists, is working on a compact fusion reactor called SPARC. SPARC aims to use high-temperature superconducting magnets to confine plasma more efficiently than traditional tokamaks. This could make fusion reactors smaller, cheaper, and quicker to build. CFS plans to have SPARC operational by the mid-2020s, with the goal of demonstrating net energy gain from nuclear fusion, a major step toward commercial viability.

KSTAR (Korea Superconducting Tokamak Advanced Research)

KSTAR, located in South Korea, is a magnetic confinement tokamak experiment aiming to develop stable plasma confinement and advanced control technologies. In 2020, KSTAR set a world record by sustaining plasma at temperatures of 100 million degrees Celsius for 20 seconds. This achievement brings researchers closer to maintaining the ultra-high temperatures needed for sustained fusion reactions, and the team continues to push toward longer plasma confinement times. KSTAR’s research is crucial in advancing the technology needed for future fusion reactors.

Future Predictions of Nuclear Fusion

Nuclear fusion, long considered the ultimate clean energy solution, is approaching a potential breakthrough as significant progress has been made in recent years. Below are key predictions for the future of nuclear fusion and its role in the global energy landscape.

The timeline for achieving commercial nuclear fusion has been elusive for decades. However, experts are now more optimistic. Many predict that fusion reactors could become commercially viable by the 2050s.

Projects like ITER aim to demonstrate that net-positive energy production is feasible by the 2030s, with commercial-scale plants following in subsequent decades. These reactors will produce clean, safe, and virtually limitless energy, without the long-lived radioactive waste of nuclear fission.

Computing Demands And Trends

Our computing demands are analogous to our energy demands. Our ancestors had little recourse to computation. They used simple symbolism. This led to mathematics and the computing revolution of today. But just as the trend for energy consumption has risen rapidly, so has the computational need. Almost every human has some form of computational device: a phone, a calculator, or a computer.

Technologies like AI have ushered in an era of computation in which more computation is required. Consider the computations needed to buy something from an e-commerce online store. They are vast and unimaginable compared to only a century ago. But more than just transactions, we increasingly rely on computational power for almost every aspect of our lives.

The explosive growth of data in recent decades has been a primary driver of the rising demand for computational power. The advent of the internet, cloud computing, and the Internet of Things (IoT) has generated unprecedented amounts of data every second.

This data explosion has given rise to big data analytics, which requires advanced computing systems to process, store, and analyze vast datasets in real time.

Artificial Intelligence is part of that trend. We rely more and more on machines for decisions. Thanks to Gen AI, machines are even creating.

Quantum Computing

It’s important to know what quantum computing is and isn’t. Quantum computing is not a replacement for classical computing or AI. Yet, it does offer hope as a potential disruptive paradigm-shifting technology for certain types of computation.

As AI has pioneered specialist devices for specific calculations, Quantum Computing can compute certain algorithms more efficiently. Quantum Computation is not a panacea for the limits of classical computation like Moore’s Law. As developments progress in QC, further algorithms may be helpful in the growing Quantum Zoo and algorithms.

Nuclear Fusion vs. Quantum Computing

So, to answer the original question, will computing always be 50 years away, as nuclear fusion is always purported to be? We don’t think so. Let’s outline some thinking behind this answer that may not be immediately obvious.

Quantum is already here.

Unlike NF (Nuclear Fusion) which is showing the promise of very spurious sustainable fusion reactions, quantum computing is being done today in labs, private and public companies.

Quantum, like NF, needs scale. The number of available qubits right now is quite small. Companies such as IBM and other early quantum pioneers have already reached several thousand qubits (qubits are the building blocks of any quantum computer).

There are roadmaps continually showing progress, and there is a lot of confidence that scaling is possible, and companies have publicly committed to these roadmaps.

The Quantum Ecosystem is vast.

Unlike NF, the cost of entry is relatively much lower. You can even buy a small-scale quantum computer that sits on your desktop. You cannot do big science like NF without massive (i.e. billions) in funding.

Big science is crucial, but incremental improvements can accure from the vast cambrian explosion of quantum companies that range from tens of people to tens of thousands of staff.

There are hundreds of start-up quantum companies developing everything from control systems to providing consultancy in this nascent field. We’ve tracked these companies as they evolve and grow the quantum landscape.

Private vs. Public Funding.

To our knowledge, only government and university labs can afford research in NF. Contrast this with the rapid growth of small quantum computing companies. Many quantum tech companies are emerging to capture a share of the quantum market. NF requires massive budgets, space, cooperation, and risk.

Talent availability.

Many will argue that the 1950s were the heyday for nuclear power. It was the promised land. There were even nuclear-powered cars. The concept of nuclear-powered cars gained popularity during the 1950s and 1960s. Enthusiasm for atomic energy was at its peak during that time.

The Ford Nucleon was a futuristic car design introduced in 1958. It envisioned a small nuclear reactor in the car’s rear, providing it with a theoretical range of thousands of miles without refueling. However, due to insurmountable technical and safety concerns, the Nucleon never reached the conceptual stage.

Today, there isn’t the fascination with nuclear physics and science that there once was. The proposed atomic revolution never happened, and the bright kids, instead, today, have gone into AI, Data, and Quantum. Whilst nuclear physics is a part of the undergraduate syllabus of many physics degrees, it doesn’t have the same universality as the teaching of quantum mechanics, which underpins quantum computing.

Quantum Cloud vs. Massive Laboratory

If you want to learn QC, you can easily do so and also program a real quantum computer. IBM has offered public access to quantum computers since 2018. So, there is little barrier to playing, learning, and exploring quantum computing. Contrast this to NF. You can access a QC via the cloud.

Understanding and Comprehension. Quantum mechanics is on a firm foundation, not that NF isn’t. However, the principles that underpin critical principles of quantum computation, such as quantum mechanics, namely entanglement and supervision, can be explained quite clearly and easily. There are numerous tutorials on the web, as well as numerous textbooks.

So even if you never actually program a real world quantum computer, you can learn how one works and even simulation some basic gate operations.

The Future of Quantum Computing

The developments in Quantum Computing are too numerous to include in a single article. But here are some of the key metrics driving the field forward.

Quantum Error Correction

Current quantum computers are still in the experimental phase and heading towards commercialism. They are known as noisy intermediate-scale quantum devices, or NISQ. The goal is to achieve large-scale, fault-tolerant quantum computing. Quantum error correction is one of the primary challenges, as today’s quantum systems are highly susceptible to noise and errors.

As quantum computing advances, the focus is on improving logical qubits. Implementing effective quantum error correction (QEC) strategies has become paramount. Quantum systems are inherently susceptible to errors due to decoherence and noise. This susceptibility makes error correction critical for the practical deployment of quantum computers. Recent developments in both areas have shown promise in making quantum computing more robust and scalable.

Logical qubits are abstract representations of quantum bits (qubits) constructed using multiple physical qubits. The primary goal of logical qubits is to improve error rates and maintain quantum coherence over extended periods. This is essential for executing complex quantum algorithms. Physical qubits are subject to various error types, such as bit flips, phase flips, and depolarization. Logical qubits can correct these errors. They do this through redundancy and sophisticated encoding.

Quantum companies like Quera have been pioneering the development of logical qubits, which can lead to truly scalable Quantum Computers.

Scaling the Number of Qubits

Creating error-free or low-error qubits is crucial. Researchers must also increase the number of available qubits to be truly useful. Scaling the number of qubits is a critical challenge in developing practical quantum computers. Quantum algorithms need more qubits to solve complex problems. Thus, efficiently and reliably increasing qubit count is essential. This increase is vital for achieving quantum advantage over classical systems.

Companies such as PsiQuantum have made public their quest to reach one million qubits—that’s one million qubits—a gain of three orders of magnitude over the typical system today. It’s not an empty promise, either, with some of any quantum computing company’s most significant raises and investments. They are serious—very serious—about building utility-scale quantum computers.

New Metrics for Understanding Quantum Performance

There has been an evolution in measuring quantum computer performance. It began with a simple measure of qubit count. This method doesn’t consider the quality of those qubits or the way they are connected. Hence, more elaborate schemes have been formulated. Still, I think the pure qubit count will remain as it, by proxy, includes some implicit usability.

Quantum Volume (QV) is a comprehensive metric used to assess the performance and capability of a quantum computer. IBM introduced it in 2019 as a way to quantify the computational power of a quantum system. This metric considers various factors that affect performance. Traditional metrics may focus solely on the number of qubits. In contrast, quantum volume considers the interaction between qubit count, gate fidelity, connectivity, and error rates.

IBM introduced the Quantum V-Score performance metric. It assesses the capabilities of quantum computing systems, which particularly use quantum volume (QV) as a foundational measure. The Quantum V-Score extends the concept of quantum volume by providing a more granular and application-specific evaluation of quantum hardware. This metric helps users understand how well a quantum computer performs various tasks. It focuses particularly on real-world quantum algorithms and applications.

Quantum Computing Won’t Be Like Nuclear Fusion

We’ve outlined why Quantum Computing won’t be like the promise of Nuclear Fusion. Like Fusion, we know the science works for quantum computing, but it’s just a matter of scaling up. There are numerous points to consider. Many eyeballs are working on quantum computing. Compared to nuclear fusion, we feel more assured that there will be significant progress in quantum computing before nuclear fusion.