Quantum computing is a fundamentally different approach to processing information that exploits the principles of quantum mechanics to solve problems that are intractable for even the most powerful classical supercomputers. Rather than encoding data as binary digits (bits) that are strictly 0 or 1, quantum computers use quantum bits (qubits) that can exist in a superposition of both states simultaneously, enabling massively parallel computation on certain classes of problems. The field has moved from theoretical curiosity to an industry generating over $1 billion in annual revenue, backed by more than $54 billion in cumulative government investment worldwide and attracting multi-billion-dollar valuations for companies building the hardware and software that will define the next era of computing.

The pace of progress has accelerated dramatically. Google demonstrated exponential error suppression with its 105-qubit Willow chip, IBM delivered its Nighthawk processor capable of running circuits with 5,000 two-qubit gates, Microsoft unveiled Majorana 1 as a proof-of-concept for topological qubits, and researchers at Caltech assembled the largest neutral atom qubit array to date at 6,100 qubits. The number of peer-reviewed papers on quantum error correction surged from 36 in all of 2024 to 120 in the first ten months of 2025 alone. These are not incremental gains. The industry is approaching an inflection point where quantum computers begin to deliver measurable advantage over classical methods for commercially relevant problems.

This guide provides a comprehensive, technically grounded explanation of what quantum computing is, how it works, what it can and cannot do, and where the technology stands today. It is written for anyone who wants to understand the field properly, whether you are an investor evaluating quantum computing stocks, a technologist exploring the space, a student considering a career, or a business leader assessing the implications for your industry.

How Classical Computing Works and Why It Has Limits

To understand quantum computing, it helps to understand what it is replacing and why. Classical computers, the machines we use every day from smartphones to the world’s largest supercomputers, process information using transistors that represent data as binary digits. Each bit is either 0 or 1 at any given moment. Every operation a classical computer performs, from rendering a web page to simulating weather patterns, ultimately reduces to manipulating these binary values through logic gates that perform simple Boolean operations like AND, OR, and NOT.

This approach is spectacularly successful. Modern processors contain billions of transistors, clock speeds measure in gigahertz, and the accumulated effect of decades of engineering following Moore’s Law has given us machines of extraordinary capability. The world’s fastest supercomputer, El Capitan at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, achieves over two exaflops of peak performance. For the vast majority of computational tasks, classical computers are more than adequate, and they will remain so for the foreseeable future.

The limitations become apparent when you encounter problems where the number of possible solutions grows exponentially with the size of the input. Consider simulating the behaviour of a molecule. A relatively simple molecule like caffeine, with 24 atoms, requires tracking quantum interactions among its 238 electrons. The quantum state space of this system is so large that representing it precisely would require more classical bits than there are atoms in the observable universe. This is not a limitation of engineering. It is a fundamental mathematical barrier. No amount of additional transistors or faster clock speeds will overcome it, because the problem scales exponentially while classical resources scale linearly.

This is where quantum computing offers something genuinely different. By encoding information in quantum mechanical systems that naturally exhibit the same physics as the problems being simulated, quantum computers can represent and manipulate exponentially large state spaces using a number of qubits that grows only linearly with the size of the system. A quantum computer with a few hundred high-quality, error-corrected qubits could simulate molecular systems that no classical computer could ever touch.

Classical Computing vs Quantum Computing at a Glance

| Classical Computing | Quantum Computing | |

|---|---|---|

| Basic unit | Bit (0 or 1) | Qubit (superposition of 0 and 1) |

| Processing | Sequential logic gates | Quantum gates on superposed states |

| Parallelism | Simulated (multi-core, threading) | Inherent (exponential state space) |

| Error rates | Roughly one error per billion billion operations | Roughly one error per 100 to 1,000 operations (improving) |

| Operating temperature | Room temperature | Near absolute zero (15 mK) for superconducting; room temp for photonic |

| Maturity | Billions of transistors, decades of refinement | Hundreds to thousands of qubits, rapidly advancing |

| Best for | General-purpose computation, data processing, AI training | Molecular simulation, cryptography, optimisation, sampling |

| Energy per operation | Extremely low (picojoules) | High (dilution refrigerators draw ~25 kW) |

| Programming | C, Python, Java, etc. | Qiskit, Cirq, PennyLane (Python-based) |

| Commercial availability | Ubiquitous | Cloud access (IBM, AWS, Azure); on-premise systems $10M+ |

The Physics Behind Quantum Computing

Quantum computing rests on three fundamental principles of quantum mechanics that have no analogue in everyday experience. These are superposition, entanglement, and interference. Each is experimentally verified to extraordinary precision, and their exploitation is what gives quantum computers their potential computational advantage.

This section includes mathematical notation to provide precision for readers with a technical background. Each equation is followed by a plain-language explanation, so readers unfamiliar with the formalism can skip the notation without losing the thread.

Superposition is the principle that a quantum system can exist in multiple states simultaneously until it is measured. A classical bit is definitively 0 or 1. A qubit, by contrast, exists in a state described by a linear combination of the two computational basis states. This combination is written using two complex numbers called probability amplitudes, typically labelled alpha and beta.

The two amplitudes are not arbitrary. The squared magnitudes of alpha and beta represent the probabilities of finding the qubit in the zero state or the one state when measured, and those probabilities must sum to one. This normalisation constraint is expressed as follows.

When you measure the qubit, it collapses to one of the two basis states. The probability of each outcome is determined by the squared magnitude of the corresponding amplitude. Before measurement, the qubit genuinely is in both states at once. This is not uncertainty or ignorance about the true state. It is the actual physical reality, confirmed by nearly a century of experimental evidence. Geometrically, the state of a single qubit can be represented as a point on the Bloch sphere, parameterised by two angles: a polar angle theta running from zero to pi and an azimuthal angle phi running from zero to two pi.

Every possible single-qubit state maps to exactly one point on this sphere, with the north pole corresponding to the zero state and the south pole to the one state. The Bloch sphere is one of the most useful visualisations in quantum computing because it makes abstract quantum states geometrically intuitive.

The power of superposition becomes clear when you consider multiple qubits together. Two classical bits can represent one of four states at any moment: 00, 01, 10, or 11. Two qubits in superposition can represent all four states simultaneously. More generally, a system of n qubits can exist in a superposition of all possible states at once, with the total number of simultaneous states doubling for every additional qubit. The general state is a weighted sum over every basis state in the system.

The scaling is exponential. Three qubits can represent eight states. Ten qubits can represent 1,024 states. Fifty qubits can represent over one quadrillion states. With just 300 qubits in full superposition, the number of simultaneous states exceeds the estimated number of particles in the observable universe. This exponential scaling of the state space is the fundamental source of quantum computing’s potential advantage.

Entanglement is a correlation between quantum particles that has no classical equivalent. When two qubits become entangled, their quantum states become linked such that measuring one instantly determines the state of the other, regardless of the physical distance separating them. The simplest and most studied entangled state is the Bell state, in which two qubits share an equal superposition of both being in the zero state and both being in the one state.

Neither qubit in this state has a definite value on its own. But if you measure the first qubit and find it in the zero state, the second qubit is guaranteed to be in the zero state as well, and vice versa for the one state. This correlation is stronger than anything permitted by classical physics, a fact formalised by Bell’s inequality. Einstein famously called this “spooky action at a distance,” and it troubled him deeply, but decades of experimental tests (most notably the Bell test experiments that won the 2022 Nobel Prize in Physics for Alain Aspect, John Clauser, and Anton Zeilinger) have confirmed that entanglement is real and that no classical mechanism can explain it.

There are four maximally entangled two-qubit states, known collectively as the Bell basis. Together, they form the fundamental building blocks for quantum teleportation, superdense coding, and many quantum error correction protocols.

Any two-qubit quantum state can be expressed as a combination of these four Bell states, making them as foundational to quantum information theory as the single-qubit basis states are to single-qubit physics.

In quantum computing, entanglement is used to create correlations between qubits that enable computation across the entire quantum state space simultaneously. Without entanglement, each qubit would be independent, and you would gain no advantage over processing them classically one at a time. Entanglement is what ties the exponentially large state space together into a coherent computational resource. It is the essential ingredient that makes quantum algorithms work.

Interference is the mechanism by which quantum computations produce useful answers. Because probability amplitudes are complex numbers, they can add constructively (reinforcing each other) or destructively (cancelling each other out). If two computational paths lead to the same output state, their amplitudes combine. When those amplitudes share the same phase they reinforce, and when they have opposite phase they cancel. The probability of measuring a particular outcome depends on the squared magnitude of the combined amplitude. A quantum algorithm is essentially a carefully designed sequence of operations that manipulates these amplitudes so that the probability of measuring the correct answer is amplified while the probability of measuring wrong answers is suppressed. This is directly analogous to how waves interfere in physics, where peaks meeting peaks create larger peaks and peaks meeting troughs cancel out.

The combination of these three effects is what makes quantum computing powerful. Superposition allows a quantum computer to explore many possibilities simultaneously. Entanglement creates correlations across those possibilities that would be impossible to represent efficiently on a classical machine. Interference extracts the correct answer from the exponentially large space of possibilities. Remove any one of these three ingredients and the quantum advantage disappears.

How a Quantum Computer Actually Works

The abstract physics described above must be realised in physical hardware, and this is where quantum computing becomes an extraordinary engineering challenge. A quantum computer consists of several key components that work together to initialise qubits, apply quantum logic gates, and read out results.

At the core is the quantum processor, which contains the physical qubits. These are real physical systems, whether superconducting circuits cooled to temperatures colder than outer space, individual atoms trapped by laser beams, photons routed through optical circuits, or electrons confined in semiconductor quantum dots. Each approach has different strengths and weaknesses in terms of qubit quality, scalability, connectivity, and manufacturing feasibility.

Surrounding the processor is a classical control system that generates precisely timed microwave pulses, laser beams, or electrical signals to manipulate the qubits. The timing precision required is extraordinary, typically measured in nanoseconds for superconducting systems or microseconds for trapped ions. Any imprecision in these control signals introduces errors into the computation. The control electronics for a quantum computer can fill entire rooms, and reducing this overhead is one of the major engineering challenges the industry faces.

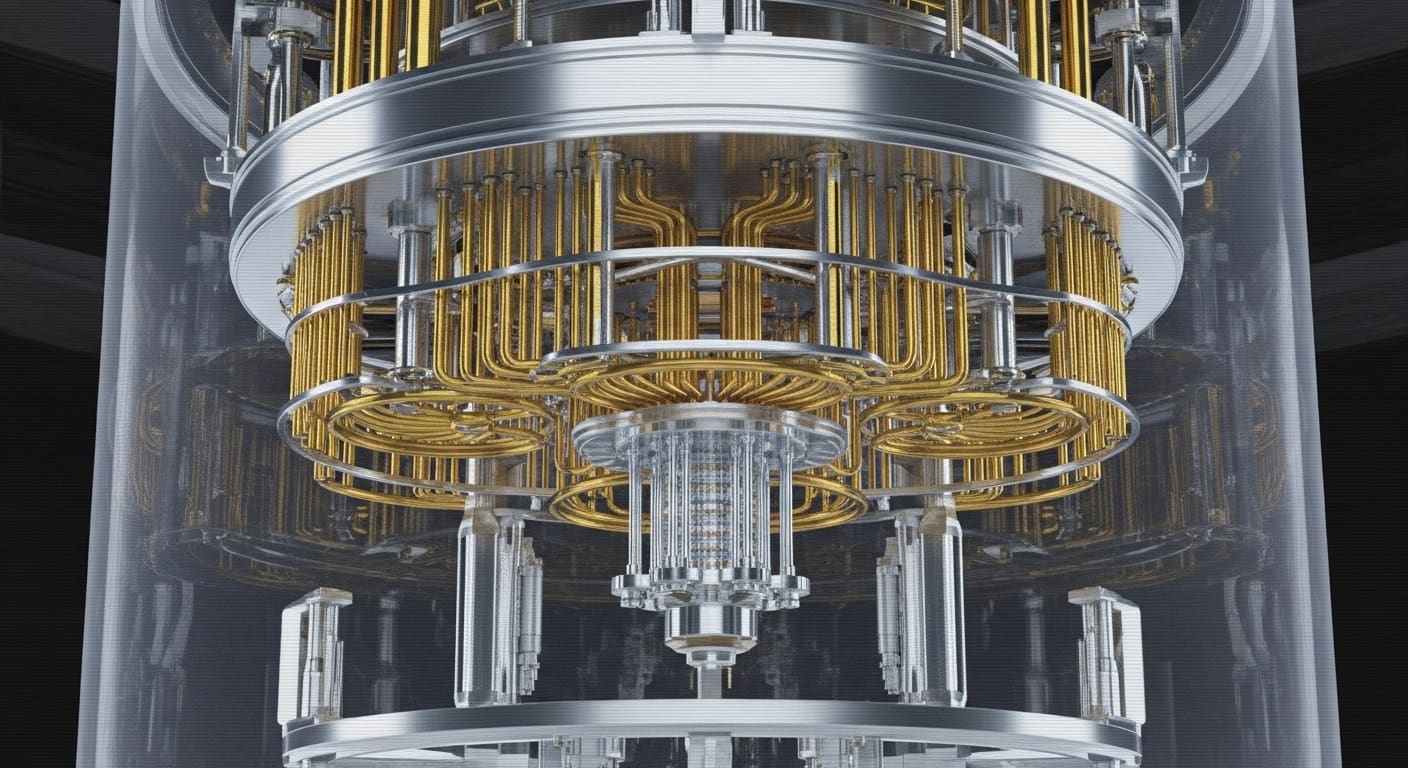

For superconducting quantum computers, which are the approach pursued by IBM, Google, and Rigetti, the processor must be cooled to approximately 15 millikelvin, roughly 0.015 degrees above absolute zero. This is achieved using a dilution refrigerator, a complex apparatus that uses a mixture of helium-3 and helium-4 isotopes to reach these extreme temperatures. The refrigerator is necessary because superconducting qubits are fabricated from materials (typically aluminium on silicon) that only exhibit the quantum behaviour needed for computation at these temperatures. Any thermal noise would destroy the delicate quantum states almost instantly.

A quantum computation proceeds in three phases. First, the qubits are initialised, typically to the zero state. Second, a sequence of quantum gates is applied to the qubits. These gates are the quantum equivalent of classical logic gates, but they operate on probability amplitudes rather than definite bit values and are represented mathematically as unitary matrices. The most important single-qubit gate is the Hadamard gate, which transforms a basis state into an equal superposition of the zero and one states.

The Pauli-X gate is the quantum equivalent of a classical NOT gate. It flips the zero state to the one state and vice versa, as shown by its matrix representation and its action on the zero state.

The CNOT (controlled-NOT) gate is the most important two-qubit gate. It flips the target qubit if and only if the control qubit is in the one state, and it is the primary mechanism for creating entanglement between qubits. Its four-by-four matrix acts on two qubits simultaneously.

Applying a Hadamard followed by a CNOT to two qubits produces the Bell state described earlier, demonstrating how entanglement is created in practice. Phase rotation gates adjust the relative phase between basis state components, and the combination of Hadamard, CNOT, and arbitrary single-qubit rotations is sufficient to implement any quantum computation, forming what is known as a universal gate set.

The full sequence of gates constitutes the quantum circuit, which is the quantum equivalent of a classical program. Third, the qubits are measured, collapsing the superposition and producing a classical bit string as output. Because the output is probabilistic, quantum circuits are typically run many times (thousands or tens of thousands of shots) and the results are aggregated statistically.

The software stack for quantum computing has matured considerably. Frameworks like Qiskit (developed by IBM), Cirq (developed by Google), and PennyLane (developed by Xanadu) allow developers to write quantum circuits in Python, compile them for specific hardware, and execute them either on simulators or on real quantum processors accessed through the cloud. Amazon Braket, Azure Quantum, and IBM Quantum all offer cloud-based access to quantum hardware, making it possible for anyone with an internet connection to run experiments on real quantum processors.

Types of Quantum Computers

There is no single way to build a quantum computer. Multiple physical approaches are being pursued simultaneously, each with distinct advantages and trade-offs. The field has not yet converged on a winner, and it is entirely possible that different approaches will prove optimal for different applications.

Superconducting qubits are the most mature approach and the one used by IBM, Google, and Rigetti. These qubits are fabricated using standard semiconductor manufacturing techniques, which is a significant advantage for eventual mass production. They offer fast gate speeds (typically tens of nanoseconds) but relatively short coherence times (typically hundreds of microseconds). IBM’s Nighthawk processor, delivered in late 2025, features 120 qubits with improved connectivity and supports circuits with up to 5,000 two-qubit gates. IBM’s roadmap targets fault-tolerant quantum error correction by 2029 and anticipates that verified quantum advantage will be confirmed by the end of 2026.

Trapped ion qubits are used by IonQ and Quantinuum (formed from the merger of Honeywell Quantum Solutions and Cambridge Quantum Computing). Individual atoms are held in place by electromagnetic fields in a vacuum chamber and manipulated using precisely targeted laser beams. Trapped ions offer the highest gate fidelities of any qubit technology, with Oxford Ionics reporting state preparation and measurement fidelity of 99.9993%. They also have much longer coherence times than superconducting qubits, measured in seconds rather than microseconds. The trade-off is slower gate speeds and challenges with scaling to large numbers of qubits in a single trap. Quantinuum’s system currently holds the record for quantum volume, a composite benchmark measuring the overall capability of a quantum computer.

Neutral atom qubits are a rapidly advancing approach pursued by QuEra, Pasqal, and Atom Computing. Individual atoms (not ions) are held in arrays created by focused laser beams called optical tweezers. The atoms can be physically moved and rearranged during computation, providing flexible connectivity between qubits. This approach has demonstrated exceptional scaling potential. Researchers at Caltech recently assembled an array of 6,100 neutral atom qubits with coherence times of 13 seconds, ten times longer than previous records. Both QuEra and Atom Computing expect to put 100,000 atoms in a single vacuum chamber within the next few years, providing a clear path toward the large qubit counts needed for fault-tolerant computation.

Photonic qubits are used by Xanadu and PsiQuantum. Information is encoded in individual photons and processed using optical circuits made from beam splitters, phase shifters, and photon detectors. Photonic systems operate at room temperature (a significant practical advantage) and are inherently compatible with existing telecommunications infrastructure, making them natural candidates for quantum networking. PsiQuantum has raised over $1 billion to build a large-scale photonic quantum computer and is developing its systems using standard silicon photonics manufacturing, which could enable mass production. The challenge with photonic approaches is that photons do not naturally interact with each other, making two-qubit gates difficult to implement deterministically.

Silicon spin qubits are being developed by Intel and Diraq. These qubits use the spin of individual electrons or atomic nuclei confined in semiconductor quantum dots, fabricated using technology similar to existing CMOS manufacturing processes. The potential advantage is enormous: if quantum processors can be manufactured in the same facilities that produce classical chips, the path to mass production and miniaturisation becomes much clearer. The challenge is that silicon spin qubits are extremely small, making precise control and readout technically demanding.

Topological qubits represent Microsoft’s long-term bet. In February 2025, Microsoft unveiled Majorana 1, an eight-qubit chip based on a novel class of materials called topoconductors that can create and control Majorana zero modes, exotic quasiparticles that store quantum information non-locally. The theory predicts that topological qubits should be inherently more resistant to errors than other approaches because the quantum information is distributed across the physical system rather than stored in a single fragile state. Microsoft claims the architecture can scale to a million qubits on a single chip. However, the scientific community has raised significant questions about Microsoft’s evidence, with independent researchers publishing critiques of the experimental protocols and questioning whether genuine Majorana zero modes have been conclusively demonstrated. DARPA has nevertheless selected Microsoft to advance to the final phase of its quantum benchmarking programme.

Quantum annealers are a specialised class of quantum computer built by D-Wave. Unlike the gate-based quantum computers described above, which can run arbitrary quantum algorithms, annealers are designed specifically for optimisation problems. They work by encoding a problem into an energy landscape and allowing the system to evolve toward the lowest energy state, which corresponds to the optimal solution. D-Wave’s latest systems feature over 5,000 qubits and have been used for logistics, scheduling, and machine learning applications. In early 2026, D-Wave announced a breakthrough in embedding cryogenic control directly on-chip for gate-model processors, signalling its intent to compete in the universal quantum computing space as well.

Qubit Technologies Compared

| Technology | Gate Speed | Coherence Time | Gate Fidelity | Max Qubits (2026) | Operating Temp | Key Players |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Superconducting | ~10-100 ns | ~100-500 μs | ~99.5-99.9% | ~1,000+ | 15 mK | IBM, Google, Rigetti |

| Trapped Ion | ~1-100 μs | seconds to minutes | ~99.9%+ | ~50-60 | Room temp (trap), UHV | IonQ, Quantinuum |

| Neutral Atom | ~1-10 μs | ~1-13 s | ~99.5% | ~6,100 | ~10 μK | QuEra, Pasqal, Atom Computing |

| Photonic | ~ps-ns | N/A (no memory) | ~99% (linear) | varies | Room temp | Xanadu, PsiQuantum |

| Silicon Spin | ~1-10 ns | ~ms-s | ~99%+ | ~10s | 15 mK | Intel, Diraq |

| Topological | projected fast | projected long | projected high | 8 (proof of concept) | 15 mK | Microsoft |

| Annealing | N/A (continuous) | ~20 μs | N/A | ~5,000+ | 15 mK | D-Wave |

What Quantum Computers Can Do

The potential applications of quantum computing span multiple industries, but it is important to be precise about where quantum computers offer a genuine advantage rather than simply being an alternative way to perform the same calculations a classical machine could handle.

Molecular simulation and drug discovery is widely considered the most natural application for quantum computing, because quantum computers are literally simulating quantum physics. Classical computers struggle to represent the quantum state of molecules beyond a certain size because the number of variables grows exponentially with the number of electrons. Quantum computers can represent these states naturally. This has direct applications in pharmaceutical research (simulating how drug candidates interact with target proteins), materials science (designing new catalysts, batteries, and superconductors), and agricultural chemistry (improving fertiliser production through better understanding of nitrogen fixation). Companies like Roche, Merck, BASF, and BMW are already partnering with quantum computing companies to explore these applications. The Quantum Navigator tracks hundreds of companies active in quantum chemistry and materials simulation.

Cryptography and cybersecurity is the application that generates the most public concern. Shor’s algorithm, published by mathematician Peter Shor in 1994, demonstrated that a sufficiently powerful quantum computer could factor large numbers exponentially faster than any known classical algorithm. The best known classical factoring algorithm (the general number field sieve) runs in sub-exponential time, while Shor’s algorithm runs in polynomial time, representing an exponential speedup. Since the security of widely used encryption protocols like RSA depends on the difficulty of factoring large numbers (the RSA-2048 standard uses a 2048-bit key, meaning the number to be factored has roughly 617 decimal digits), a fault-tolerant quantum computer could potentially break much of the encryption that secures the internet, financial systems, and government communications. This has spurred a global effort to develop and deploy post-quantum cryptography, with NIST publishing its first set of post-quantum encryption standards and governments worldwide mandating migration timelines. The “harvest now, decrypt later” threat, where adversaries collect encrypted data today with the intention of decrypting it once quantum computers become powerful enough, has made this an urgent priority even though fault-tolerant quantum computers capable of running Shor’s algorithm at scale are still years away.

Optimisation is a broad category encompassing financial portfolio optimisation, logistics and supply chain routing, network design, scheduling, and resource allocation. Many of these problems are NP-hard, meaning that the time required to find the optimal solution grows exponentially with the problem size on classical computers. Grover’s search algorithm provides a proven quadratic speedup for unstructured search problems, reducing the number of evaluations required from N to the square root of N. For a database with a billion entries, this means roughly 31,623 quantum evaluations instead of a billion classical checks. Quantum algorithms like the Quantum Approximate Optimisation Algorithm (QAOA) and variational quantum eigensolver (VQE) offer potential speedups for certain classes of optimisation problems, though the extent of quantum advantage for practical optimisation remains an active area of research.

Machine learning and artificial intelligence is an area of intense investigation where the overlap between quantum computing and AI is growing rapidly. Quantum approaches to machine learning include quantum kernel methods (using quantum computers to compute similarity measures between data points in high-dimensional spaces), quantum neural networks, and quantum-enhanced sampling for training generative models. While definitive quantum advantage for machine learning has not yet been demonstrated at practical scale, the theoretical potential is significant, and this crossover domain is attracting substantial investment from both the quantum and AI communities.

Financial modelling is one of the nearest-term commercial applications. Monte Carlo simulations, used extensively in finance for risk analysis, derivatives pricing, and portfolio optimisation, could see quadratic speedups from quantum algorithms. JPMorgan Chase recently achieved a milestone with the implementation of a quantum streaming algorithm that demonstrates theoretical exponential space advantage in real-time processing of large datasets. Goldman Sachs, HSBC, Barclays, and other major financial institutions maintain active quantum computing research programmes.

Energy and climate science presents another compelling set of use cases. Quantum computers could accelerate the discovery of new materials for more efficient solar cells, improve the design of catalysts for carbon capture, and optimise the management of complex energy grids that must balance intermittent renewable generation with demand in real time. The simulation of high-temperature superconductors, which could revolutionise energy transmission, is a problem that is fundamentally quantum mechanical in nature and is expected to be among the first to see meaningful quantum advantage.

Defence and national security applications drive a significant portion of government investment in quantum computing. These include signals intelligence, cryptanalysis, logistics optimisation for military operations, and quantum sensing applications such as submarine detection using quantum magnetometers and GPS-independent navigation using quantum inertial sensors. DARPA’s Quantum Benchmarking Initiative and the US Department of Energy’s Genesis Mission reflect the strategic importance governments attach to maintaining quantum computing leadership.

What Quantum Computers Cannot Do

Popular coverage of quantum computing frequently overstates its capabilities, and a clear understanding of the limitations is essential for anyone evaluating the technology seriously.

Quantum computers will not replace classical computers. They are not faster at running spreadsheets, rendering video, serving web pages, or executing the vast majority of everyday computational tasks. For problems that do not have the mathematical structure that quantum algorithms can exploit, a classical computer will always be more practical, more reliable, and vastly cheaper. The correct mental model is that quantum computers are specialised accelerators for specific problem types, analogous to how GPUs accelerated graphics and then machine learning without replacing CPUs for general computation.

Quantum computers do not try all possible solutions simultaneously, despite this being a common misconception. Superposition allows a quantum computer to represent many states at once, but measuring the system collapses it to a single answer. The art of quantum algorithm design lies in using interference to amplify the probability of the correct answer. Without a cleverly designed algorithm, a quantum computer gives you a random answer, not every answer.

Current quantum computers are noisy. Qubits are extraordinarily sensitive to environmental disturbances, and every operation introduces some probability of error. The error rates on today’s best hardware, while rapidly improving, are still orders of magnitude higher than classical computing. IBM’s current systems can reliably execute circuits with a few thousand operations; classical processors can execute trillions of operations without a single error. This noise limits the size and complexity of problems that current quantum computers can solve usefully.

Scaling quantum computers is enormously difficult. Adding more qubits is not like adding more RAM to a classical computer. Each additional qubit must maintain quantum coherence with all the others, and the control systems become exponentially more complex. This is why the industry’s focus has shifted from raw qubit counts to metrics like gate fidelity, coherence time, and circuit depth, which more accurately reflect a quantum computer’s practical capability.

The NISQ Era and the Road to Fault Tolerance

The current generation of quantum computers is described as Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) devices, a term coined by physicist John Preskill in 2018. NISQ machines have enough qubits to be interesting (hundreds to low thousands) but too many errors to run the deep circuits required by algorithms like Shor’s that promise the most dramatic advantages.

The central challenge facing the field is quantum error correction (QEC). The idea is to encode a single “logical qubit” using many physical qubits, distributing the quantum information across the group so that errors affecting individual physical qubits can be detected and corrected without destroying the computation. This is conceptually similar to classical error correction but far more demanding because of the no-cloning theorem (you cannot copy an arbitrary quantum state) and the fragility of quantum superposition. The threshold theorem proves that if the error rate per physical gate is below a certain threshold, then arbitrarily long quantum computations can be performed reliably by using enough physical qubits per logical qubit. For the surface code, one of the most studied QEC approaches, this threshold is approximately one percent, and the number of physical qubits required per logical qubit scales inversely with the physical error rate.

The progress in QEC has been remarkable. Google’s Willow chip demonstrated that as the size of error-correcting codes increases (from a three-by-three to a seven-by-seven lattice), the logical error rate decreases exponentially. Specifically, each increase in code distance roughly halved the logical error rate. This is a critical result that proves error correction actually works at the physical level.

IBM’s experimental Loon processor demonstrated all the key components needed for fault-tolerant quantum computing, including on-chip routing layers that connect distant qubits and real-time error decoding in under 480 nanoseconds. The diversity of QEC approaches has exploded, with surface codes, colour codes, qLDPC codes, bosonic cat qubit codes, and Floquet codes all being actively developed and tested on hardware.

Industry roadmaps converge on fault-tolerant quantum computing arriving around the end of the decade. IBM targets a fault-tolerant system by 2029 and expects verified quantum advantage to be confirmed by the wider community by end of 2026. Google’s roadmap aims for a useful, error-corrected quantum computer by 2029, building on the Willow results. Quantinuum’s Apollo programme targets universal fault tolerance by 2030. Microsoft, if its topological approach proves out, claims it could achieve fault tolerance with significantly fewer physical qubits per logical qubit than competing approaches due to the inherent error protection of topological states.

Between now and fault tolerance, the industry is pursuing hybrid quantum-classical computing, where quantum processors handle specific subroutines within larger classical workflows. This approach is already being deployed in chemistry simulation, optimisation, and machine learning, and it represents the most realistic path to near-term commercial value from quantum computing.

The Global Quantum Race

Quantum computing has become a matter of national strategic importance, and governments around the world are investing at a scale that reflects this. The competitive dynamics are reshaping the industry as much as the underlying technology.

The United States leads in private-sector investment and hosts the largest concentration of quantum hardware companies, including IBM, Google, IonQ, Rigetti, and PsiQuantum. Federal funding has been channelled through agencies including DARPA (which is running a rigorous Quantum Benchmarking Initiative aimed at procuring a commercially relevant quantum computer by 2033), the Department of Energy (which launched the Genesis Mission in late 2025 with ambitions comparable to the Manhattan Project), and the National Science Foundation. The US government has also driven urgency around post-quantum cryptography migration, with federal agencies required to begin transitioning away from RSA and other vulnerable encryption standards.

China has invested heavily in quantum technology, with particular strengths in quantum communications and quantum sensing. The country operates the world’s longest quantum communication network and has launched quantum satellites. Chinese research groups have published competitive results in photonic quantum computing and continue to produce a high volume of high-quality quantum research, though geopolitical tensions and export controls have created increasing barriers to international collaboration.

The European Union launched its Quantum Flagship programme in 2018 with an initial budget of EUR 1 billion over ten years and is preparing a Quantum Grand Challenge expected to launch in 2026. Individual European countries have added substantial national programmes on top of this. France committed EUR 1.8 billion to its national quantum strategy, Germany invested EUR 3 billion, and the Netherlands hosts a world-leading quantum ecosystem centred on TU Delft and the QuTech research centre. European companies including IQM (Finland), Pasqal (France), and ORCA Computing (UK) are competitive globally.

Japan announced a $7.4 billion national quantum programme, one of the largest single-year government outlays for quantum technology anywhere in the world. The country’s quantum strategy emphasises integration with its existing strengths in materials science, manufacturing, and high-performance computing.

The United Kingdom has established itself as a significant quantum nation despite its smaller scale, with the National Quantum Computing Centre (NQCC), strong university research programmes at Oxford, Cambridge, UCL, and Bristol, and a thriving startup ecosystem that includes Quantinuum (which retains its Cambridge research heritage), OQC, Riverlane, Phasecraft, Nu Quantum, and PQShield.

Cumulative government investment in quantum technologies worldwide now exceeds $54 billion. This is not speculative venture capital. It is strategic national investment reflecting a consensus among major governments that quantum technology will be critical to economic competitiveness, national security, and scientific leadership in the decades ahead. The scale of this commitment effectively guarantees that the field will continue to advance regardless of short-term fluctuations in private-sector enthusiasm. For investors, analysts, and business leaders looking to research the quantum market in depth, Quantum Navigator provides a searchable database of more than 940 quantum technology companies worldwide, with company profiles, funding data, technology classifications, and market intelligence across the full quantum ecosystem.

Key Companies Shaping the Industry

The quantum computing landscape includes a mix of technology giants, well-funded startups, and specialist companies across hardware, software, and applications. Quantum Zeitgeist’s Quantum Navigator tracks more than 940 companies operating in the quantum technology ecosystem. Here are some of the most significant players.

Among the technology giants, IBM operates one of the most comprehensive quantum programmes in the world, with a public roadmap extending to 2033, cloud-accessible quantum systems through IBM Quantum, and the open-source Qiskit software framework that has become the most widely used quantum development tool. Google Quantum AI made headlines with its Willow processor and continues to push the boundaries of error correction research. Microsoft has pursued a unique topological approach through its Majorana programme and offers access to third-party quantum hardware through Azure Quantum. Amazon Web Services provides access to quantum hardware from multiple vendors through Amazon Braket and is developing its own quantum processor based on cat qubits with the Ocelot chip unveiled in February 2025.

Among pure-play quantum hardware companies, IonQ (NYSE: IONQ) has the strongest balance sheet in the sector with approximately $1.6 billion in cash following a series of capital raises, and has published an accelerated roadmap targeting 2 million physical qubits by 2030. Quantinuum, formed from the merger of Honeywell Quantum Solutions and Cambridge Quantum, has achieved a $10 billion valuation and published a roadmap to fault-tolerant computing by 2030 through its Helios, Sol, and Apollo systems. Rigetti Computing (NASDAQ: RGTI) builds superconducting quantum processors and has partnered with AWS and other cloud providers. D-Wave (NYSE: QBTS) is the most commercially deployed quantum computing company, with its annealing systems used by organisations including Volkswagen, DENSO, and Lockheed Martin.

In the neutral atom space, QuEra and Pasqal have both delivered systems to national research centres and plan to scale to tens of thousands of qubits. PsiQuantum has raised over $1 billion for its photonic approach and is anticipated to pursue a public offering. Infleqtion (NYSE: INFQ), the neutral atom quantum company formerly known as ColdQuanta, completed its SPAC merger and begins trading on the New York Stock Exchange on February 17, 2026, becoming the first publicly listed neutral-atom quantum technology company. The full landscape is far broader than these headline names. For a comprehensive directory, Quantum Navigator provides detailed profiles of more than 940 companies across every segment of the quantum technology stack, from cryogenics manufacturers to quantum software platforms. For an analysis of how company roadmaps compare across modalities, see our guide to the quantum computing future.

How to Get Started with Quantum Computing

Access to quantum computing has never been easier. IBM Quantum offers free access to real quantum processors through its cloud platform, making it possible for anyone with a web browser to run quantum circuits on actual hardware. The free tier includes access to systems with up to 127 qubits and educational resources through the IBM Quantum Learning platform. Amazon Braket offers pay-per-use access to quantum hardware from IonQ, Rigetti, and Oxford Quantum Circuits, alongside fully managed quantum circuit simulation. Azure Quantum provides access to Quantinuum, IonQ, and others with free credits for new users.

For those wanting to learn the fundamentals, Qiskit provides an excellent open-source textbook that covers everything from basic quantum mechanics to advanced quantum algorithms with hands-on coding exercises. PennyLane, developed by Xanadu, is particularly strong for quantum machine learning. Cirq, developed by Google, is optimised for designing and simulating noisy intermediate-scale quantum circuits. All three frameworks are free, open source, and well documented.

Academic programmes in quantum computing have expanded rapidly. Leading universities including MIT, Stanford, Oxford, Cambridge, ETH Zurich, TU Delft, and the University of Waterloo offer dedicated quantum computing courses and degree programmes. Online platforms including Coursera, edX, and MIT OpenCourseWare offer quantum computing courses accessible to anyone. For a comprehensive guide to learning resources, educational pathways, and career opportunities, see our guide to learning quantum computing.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is quantum computing real?

Yes. Quantum computers are operational devices that can be accessed today through cloud platforms from IBM, Amazon, Google, Microsoft, and others. The underlying physics has been experimentally verified for nearly a century, and the engineering challenge of building practical quantum computers has made substantial progress. Over $54 billion in government funding has been committed globally, and the private sector has invested billions more.

When will quantum computers be available?

They are available now, through cloud access. Multiple companies offer access to real quantum hardware over the internet. On-premise quantum systems are also available for purchase, with companies including IBM, IQM, D-Wave, and others delivering systems to data centres, national labs, and research institutions. What is not yet available is a large-scale, fault-tolerant quantum computer capable of solving the most commercially impactful problems. Industry roadmaps target this capability by approximately 2029 to 2030.

Can quantum computers break encryption?

In theory, a sufficiently powerful fault-tolerant quantum computer running Shor’s algorithm could break the RSA and elliptic curve encryption that currently secures most internet communications. This is not possible with today’s quantum hardware, which lacks the qubit count and error correction needed to run Shor’s algorithm at the scale required to crack modern encryption keys. NIST has published new post-quantum cryptography standards designed to resist quantum attacks, and governments worldwide are mandating migration to these new standards. The timeline for when quantum computers might threaten current encryption is debated, with estimates ranging from the late 2020s to the mid 2030s.

How much does a quantum computer cost?

On-premise quantum systems typically cost between $10 million and $50 million or more, depending on the technology and capability. Cloud access is far more affordable, with pricing models that charge per quantum circuit execution (per shot) or per minute of processor time. Some providers offer free tiers for educational and research use. For a detailed breakdown, see our guide to quantum computer pricing.

Will quantum computers replace classical computers?

No. Quantum computers are specialised devices optimised for specific types of calculations, primarily simulation, optimisation, and certain classes of machine learning problems. For the vast majority of everyday computing tasks, classical computers will remain superior, cheaper, and more practical. The future of computing is hybrid, with quantum processors serving as accelerators for problems where they offer a genuine advantage, integrated within classical computing workflows.

What is quantum advantage?

Quantum advantage (sometimes called quantum supremacy) refers to a quantum computer solving a specific problem faster or more efficiently than any classical computer could. Google claimed quantum supremacy in 2019 with its Sycamore processor and reinforced the claim with Willow’s demonstration in late 2024. IBM anticipates that verified quantum advantage on commercially relevant problems will be confirmed by the wider scientific community by the end of 2026. It is important to note that quantum advantage has so far been demonstrated on carefully chosen problems that play to quantum strengths. Demonstrating advantage on problems of direct commercial value remains an active goal.

Which type of quantum computer is best?

There is no consensus on the best approach, and the answer may depend on the application. Superconducting qubits are the most mature and widely deployed. Trapped ions offer the highest fidelity. Neutral atoms show the most promising scaling characteristics. Photonic systems operate at room temperature and are naturally suited to networking. Topological qubits promise inherent error protection but remain in early experimental stages. Silicon spin qubits offer the most natural path to mass manufacturing. The field may ultimately support multiple platforms optimised for different use cases, much as classical computing uses CPUs, GPUs, TPUs, and FPGAs for different tasks.

How can I invest in quantum computing?

Several pure-play quantum computing companies are publicly traded, including IonQ (IONQ), Rigetti Computing (RGTI), D-Wave Quantum (QBTS), and Quantum Computing Inc (QUBT). Technology giants with significant quantum programmes include IBM, Alphabet (Google), Microsoft, and Amazon. Dedicated quantum ETFs such as the Defiance Quantum ETF (QTUM) offer diversified exposure. Several major private quantum companies, including Quantinuum, PsiQuantum, and Infleqtion, are expected to pursue public offerings in the coming years. For a comprehensive overview of quantum investment opportunities, see our guide to quantum computing stocks.

How many qubits does a quantum computer need to be useful?

This depends entirely on the application and the quality of the qubits. A few hundred high-fidelity logical (error-corrected) qubits could solve commercially valuable problems in chemistry and materials science that no classical computer can touch. For breaking RSA-2048 encryption, estimates suggest roughly one million physical qubits would be needed using current error correction schemes, though advances in QEC codes and hardware-level error protection could reduce this significantly. The industry is shifting away from raw qubit count as the primary metric and focusing instead on the total number of useful operations a quantum computer can perform before errors accumulate to unusable levels.

Is quantum computing just hype?

The underlying physics is real and has been experimentally verified for decades. The engineering challenges are genuine and significant, and some of the timelines promoted in corporate press releases are optimistic. However, the scale of investment (over $54 billion in government commitments alone), the breadth of companies pursuing multiple independent approaches, and the steady stream of demonstrated milestones in error correction, qubit quality, and system integration all indicate that this is a technology with real momentum rather than empty hype. The honest assessment is that quantum computing is further along than sceptics claim but not as close to transformative impact as some boosters suggest. The most productive stance is informed realism.

What programming language is used for quantum computing?

Most quantum computing frameworks use Python as the primary interface. Qiskit (IBM), Cirq (Google), PennyLane (Xanadu), and Amazon Braket SDK are all Python-based. The quantum circuits themselves are described using these frameworks’ APIs and compiled into hardware-specific instructions. IBM has also introduced a C++ interface to Qiskit to enable integration with high-performance computing environments. You do not need to understand quantum mechanics deeply to write quantum programmes, though understanding the basics of superposition and entanglement helps enormously in writing effective quantum algorithms.

Key Terms

For readers new to the field, here is a brief glossary of the most important terms used throughout this guide. For a complete reference covering over 100 quantum computing terms, see the Quantum Computing Glossary.

A qubit (quantum bit) is the fundamental unit of quantum information, analogous to a classical bit but capable of existing in a superposition of the zero and one states simultaneously. A logical qubit is a fault-tolerant qubit constructed from many physical qubits using error correction codes. Superposition is the quantum mechanical property allowing a qubit to exist in a combination of states simultaneously rather than being definitively zero or one. Entanglement is a quantum correlation between particles where measuring one instantly determines the state of another, regardless of distance. Decoherence is the process by which a qubit loses its quantum properties due to interaction with its environment, effectively introducing errors. Quantum error correction is the set of techniques used to protect quantum information from errors by encoding logical qubits across multiple physical qubits; the logical error rate decreases exponentially as the code distance increases, provided physical error rates are below a threshold of approximately one percent. Quantum advantage refers to a quantum computer outperforming all classical approaches on a specific problem. NISQ (Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum) describes the current generation of quantum computers, which have enough qubits to be useful for some tasks but too much noise for the most demanding algorithms. Fault tolerance is the ability of a quantum computer to continue accurate computation even in the presence of errors, achieved through quantum error correction when the physical error rate is below the required threshold.

Further Reading

Explore the full Quantum Zeitgeist guide series for deeper coverage of every aspect of the quantum computing landscape:

Quantum Computing Companies: The Definitive Directory | A searchable guide to every major player in the quantum ecosystem, from hardware manufacturers to software platforms, powered by the Quantum Navigator database of more than 940 companies.

Quantum Computing Stocks and Publicly Traded Companies | Comprehensive analysis of pure-play quantum stocks, big tech quantum exposure, pre-IPO companies to watch, and how to evaluate quantum investments.

Post-Quantum Cryptography: Complete Guide | Everything you need to know about the quantum threat to encryption, NIST standards, migration timelines, and the companies building quantum-safe security.

Quantum Computing Applications by Industry | Where quantum computing creates real value: drug discovery, finance, logistics, materials science, AI, energy, and defence.

Quantum Error Correction Explained | The central challenge of quantum computing, from surface codes to qLDPC, with the latest breakthrough results from Google, IBM, and Microsoft.

How Much Does a Quantum Computer Cost? | On-premise pricing, cloud access costs, free tiers, and total cost of ownership for quantum computing in 2026.

Quantum Computing vs Classical Computing | A detailed comparison of capabilities, limitations, and the hybrid future of computing.

Quantum Computing Glossary | Over 100 quantum computing terms defined and explained, from algorithmic qubits to variational quantum eigensolvers.

Quantum Computing Market Size and Investment Landscape | Funding data, government investment, public market performance, and market forecasts from the leading analysts.

Quantum Computing Roadmaps | Every major player’s plan: IBM, Google, Microsoft, Quantinuum, IonQ, and more, compared side by side.

Quantum Machine Learning | Where quantum meets AI: quantum kernel methods, quantum neural networks, tools, frameworks, and the companies pushing the frontier.

Learn Quantum Computing | The complete beginner’s guide: textbooks, online courses, hands-on tools, university programmes, and career paths.

Quantum Computing in the UK | Britain’s national quantum strategy, leading companies, university research, and how the UK competes globally.

Quantum Sensing | The quantum technology closest to commercial deployment: atomic clocks, magnetometers, gravimeters, and the companies building them.