The period from 1970 to 2025 marks a significant evolution in quantum information science, building upon foundational work like Bell’s Theorem which experimentally verified the non-local nature of quantum mechanics and paved the way for quantum information processing. Initial theoretical explorations focused on the potential for quantum computation, recognizing that leveraging superposition and entanglement could enable solutions to problems intractable for classical computers. This era saw the development of early quantum algorithms, such as Shor’s algorithm for factoring large numbers and Grover’s algorithm for database searching, demonstrating a potential computational advantage. The realization of physical qubits, initially using techniques like nuclear magnetic resonance, marked the transition from theory to experimental implementation, though scalability and coherence remained substantial obstacles.

The early 21st century witnessed a diversification of qubit platforms, including superconducting circuits, trapped ions, and photonic systems, each offering unique advantages and disadvantages in terms of scalability, coherence, and connectivity. Progress in quantum error correction became crucial, as maintaining the fragile quantum states of qubits proved exceptionally challenging due to environmental noise and decoherence. Simultaneously, research expanded beyond computation to encompass quantum communication, with quantum key distribution (QKD) emerging as a promising method for provably secure communication. Quantum sensing also gained momentum, with the development of sensors capable of measuring physical quantities with unprecedented precision, opening avenues for applications in diverse fields like medical imaging and materials science.

Currently, the field is characterized by a convergence of disciplines, integrating quantum technologies with artificial intelligence, materials science, and advanced manufacturing techniques. The focus is shifting towards building more robust and scalable quantum systems, developing practical quantum algorithms, and exploring hybrid quantum-classical architectures. While a fault-tolerant, universal quantum computer remains a long-term goal, near-term applications in areas like materials discovery, drug design, and financial modeling are gaining traction. Continued investment and collaborative research are essential to overcome the remaining technical hurdles and unlock the full potential of quantum information science, promising a transformative impact on science, technology, and society.

Bell’s Theorem And Local Realism

Bell’s theorem, formulated by physicist John Stewart Bell in 1964, addresses the fundamental conflict between quantum mechanics and the principles of local realism. Local realism posits that physical properties of objects have definite values independent of measurement (realism) and that an object is only directly influenced by its immediate surroundings (locality). Bell demonstrated mathematically that if local realism were true, certain statistical correlations between measurements on entangled particles would be limited to a specific range, quantified by Bell’s inequalities. These inequalities provide a testable prediction; if experiments violate them, it implies that at least one of the assumptions – locality or realism – must be false. The theorem doesn’t dictate which assumption is incorrect, only that they cannot both be simultaneously true within the framework of quantum mechanics. This is a crucial point, as it challenges our classical intuitions about how the physical world operates.

The core of Bell’s theorem lies in the concept of entanglement, a uniquely quantum phenomenon where two or more particles become linked in such a way that they share the same fate, no matter how far apart they are. When measuring a property of one entangled particle, the corresponding property of the other particle is instantly known, even if separated by vast distances. This “spooky action at a distance,” as Einstein termed it, appears to violate the principle of locality, which states that information cannot travel faster than the speed of light. However, it’s important to note that entanglement doesn’t allow for faster-than-light communication; the outcome of a measurement on one particle is random, and there’s no way to control it to send a specific message. The correlations observed in entangled systems are statistical, meaning they only become apparent when analyzing the results of many measurements.

Numerous experiments, beginning with those conducted by John Clauser and Stuart Freedman in the 1970s and significantly refined by Alain Aspect and his team in the 1980s, have consistently demonstrated violations of Bell’s inequalities. These experiments involved measuring the polarization of entangled photons and comparing the correlations between the measurements. The results unequivocally showed that the observed correlations were stronger than those allowed by local realism, providing strong evidence that at least one of the assumptions underlying local realism is incorrect. Subsequent experiments have further solidified these findings, employing various entangled systems and experimental setups to rule out potential loopholes and ensure the validity of the results.

A critical aspect of interpreting these experimental results is understanding the concept of “hidden variables.” Proponents of local realism initially suggested that quantum mechanics might be incomplete and that there might be hidden variables – unobserved properties of particles – that determine their behavior and explain the observed correlations without violating locality. However, Bell’s theorem demonstrates that any local hidden variable theory must necessarily satisfy Bell’s inequalities. Since experiments have repeatedly violated these inequalities, it effectively rules out the possibility of a local hidden variable theory explaining quantum phenomena. This doesn’t necessarily mean that hidden variables don’t exist, but if they do, they must be non-local, meaning they can instantaneously influence distant particles.

The implications of Bell’s theorem extend beyond the foundations of quantum mechanics, impacting our understanding of the nature of reality itself. It challenges the classical worldview, where objects have definite properties independent of observation and interactions are limited by the speed of light. Quantum mechanics, as confirmed by Bell’s theorem, suggests that reality is fundamentally non-local and that the act of measurement plays a crucial role in determining the properties of physical systems. This has led to interpretations of quantum mechanics, such as the Many-Worlds Interpretation, which propose that every quantum measurement causes the universe to split into multiple branches, each representing a different possible outcome.

While Bell’s theorem doesn’t provide a complete picture of quantum reality, it has profoundly shaped our understanding of the quantum world. It has spurred further research into the foundations of quantum mechanics, leading to new theoretical developments and experimental tests. The theorem has also played a crucial role in the development of quantum technologies, such as quantum cryptography and quantum computing, where entanglement is a key resource. These technologies exploit the non-local correlations between entangled particles to achieve functionalities that are impossible with classical systems.

The ongoing debate surrounding the interpretation of Bell’s theorem highlights the deep philosophical implications of quantum mechanics. While the experimental evidence overwhelmingly supports the violation of Bell’s inequalities, the question of whether locality or realism is ultimately abandoned remains a subject of ongoing discussion. Some physicists argue that it is locality that must be sacrificed, while others suggest that realism is the more problematic assumption. Regardless of the ultimate answer, Bell’s theorem has irrevocably changed our understanding of the fundamental nature of reality and continues to inspire new research and debate in the field of quantum physics.

EPR Paradox And Quantum Entanglement

The EPR paradox, formulated in 1935 by Albert Einstein, Boris Podolsky, and Nathan Rosen, challenged the completeness of quantum mechanics by proposing a scenario where the properties of particles could be known with certainty without direct measurement, seemingly violating the Heisenberg uncertainty principle. Their argument centered on the idea of local realism – the assumption that objects have definite properties independent of observation (realism) and that any influence between objects must occur at or below the speed of light (locality). The paradox involved two entangled particles, where measuring a property of one instantaneously determines the corresponding property of the other, regardless of the distance separating them. Einstein, Podolsky, and Rosen posited that quantum mechanics must be incomplete because it didn’t account for these “hidden variables” that would predetermine the particles’ properties, thus eliminating the need for instantaneous action at a distance. This critique wasn’t a rejection of quantum mechanics’ predictive power, but rather a claim that it didn’t provide a complete description of physical reality, suggesting the existence of underlying, yet unknown, variables governing particle behavior.

Quantum entanglement, the core phenomenon underlying the EPR paradox, describes a situation where two or more particles become linked in such a way that they share the same fate, no matter how far apart they are. This interconnectedness isn’t due to any physical connection or signal passing between the particles; instead, it’s a fundamental property of quantum mechanics. When entangled particles are measured, the outcome of the measurement on one particle instantaneously influences the possible outcomes of the measurement on the other, a correlation stronger than any possible under classical physics. This instantaneous correlation doesn’t allow for faster-than-light communication, as the outcome of a single measurement is random; however, the correlations between many measurements can be demonstrated and verified. The entangled state is described by a single quantum wavefunction, meaning the particles are not independent entities but rather parts of a unified system.

The implications of entanglement and the EPR paradox were largely philosophical until John Stewart Bell formulated Bell’s theorem in 1964. Bell’s theorem mathematically demonstrated that if local realism were true, certain statistical inequalities (Bell’s inequalities) would hold for the correlations observed in measurements on entangled particles. Conversely, if quantum mechanics were correct and local realism false, these inequalities would be violated. This provided a testable prediction that could differentiate between the two viewpoints. Bell’s theorem didn’t disprove quantum mechanics; it simply showed that either quantum mechanics or local realism must be incorrect. The theorem shifted the debate from philosophical argument to experimental verification, opening the door for empirical tests of the foundations of quantum mechanics.

Numerous experiments, beginning with those conducted by John Clauser in the 1970s and culminating in the definitive experiments by Alain Aspect in the 1980s and subsequent refinements, have consistently demonstrated violations of Bell’s inequalities. These experiments involved measuring the polarization of entangled photons and showed that the correlations between the measurements were stronger than any possible under local realistic theories. Aspect’s experiments, in particular, addressed potential loopholes in earlier experiments by using rapidly switching polarizers and ensuring that the measurements were made before any signal could travel between the particles. These results strongly support the predictions of quantum mechanics and refute the assumption of local realism, indicating that entangled particles are indeed interconnected in a non-classical way.

The violation of Bell’s inequalities doesn’t imply that information is being transmitted faster than light. While the correlations between entangled particles are instantaneous, the outcome of any single measurement is random. This randomness prevents the use of entanglement for sending signals faster than light, as there’s no way to control the outcome of the measurement on one particle to transmit a specific message to the other. The correlations are only revealed when the results of many measurements are compared, and this comparison requires classical communication, which is limited by the speed of light. Therefore, entanglement doesn’t violate the principles of special relativity, but it does challenge our classical intuition about locality and independence.

Despite the experimental confirmation of quantum entanglement and the refutation of local realism, the interpretation of these results remains a subject of debate among physicists. The Copenhagen interpretation, the most widely accepted interpretation of quantum mechanics, suggests that physical properties are not definite until they are measured, and that the act of measurement collapses the wavefunction. However, other interpretations, such as the many-worlds interpretation, propose that every quantum measurement causes the universe to split into multiple branches, each representing a different possible outcome. These different interpretations offer different explanations for the non-classical behavior of entangled particles, but they all agree on the experimental predictions of quantum mechanics.

The principles of quantum entanglement are not merely theoretical curiosities; they are being actively explored for potential applications in quantum technologies. Quantum cryptography, for example, uses entanglement to create secure communication channels that are immune to eavesdropping. Quantum teleportation, while not involving the transfer of matter, uses entanglement to transfer quantum states between particles. And quantum computing, the most ambitious application, aims to harness the power of entanglement and superposition to solve problems that are intractable for classical computers. These emerging technologies promise to revolutionize fields such as communication, computation, and materials science, demonstrating the profound impact of quantum entanglement on our understanding of the universe and our ability to manipulate it.

Quantum Cryptography And Key Distribution

Quantum cryptography, specifically quantum key distribution (QKD), represents a departure from classical cryptographic methods by leveraging the principles of quantum mechanics to guarantee secure communication. Unlike traditional encryption algorithms that rely on computational complexity, QKD’s security is rooted in the laws of physics, specifically the Heisenberg uncertainty principle and the no-cloning theorem. The Heisenberg uncertainty principle dictates that certain pairs of physical properties, like position and momentum, cannot be known with perfect accuracy simultaneously, while the no-cloning theorem states that an unknown quantum state cannot be perfectly copied. These principles are fundamental to QKD protocols like BB84, which utilizes the polarization of single photons to encode and transmit a cryptographic key between two parties, often termed Alice and Bob. Any attempt by an eavesdropper (Eve) to intercept and measure the quantum state will inevitably disturb it, introducing detectable errors that alert Alice and Bob to the presence of an attack.

The BB84 protocol, proposed by Charles Bennett and Gilles Brassard in 1984, forms the cornerstone of many QKD implementations. It involves Alice randomly encoding bits as one of four polarization states of photons – horizontal, vertical, diagonal, and anti-diagonal. Bob randomly chooses a basis (rectilinear or diagonal) to measure each photon. After transmission, Alice and Bob publicly compare the bases they used for encoding and measuring, discarding the bits where their bases didn’t match. This process establishes a shared, secret key. The security of BB84 relies on the fact that any attempt to measure a quantum state inevitably disturbs it, and Eve cannot distinguish between the four polarization states without introducing errors detectable by Alice and Bob during a subsequent error correction phase. This error correction, alongside privacy amplification, removes any partial information Eve might have gained, ensuring a secure key.

Practical implementations of QKD face significant challenges, primarily related to photon loss and detector imperfections. Photon loss, due to absorption or scattering in the transmission medium (fiber optic cable or free space), limits the distance over which QKD can be effectively implemented. Detector imperfections, such as dark counts (false detections) and inefficiencies, can also introduce errors and compromise security. To mitigate these challenges, researchers are exploring various techniques, including the use of low-loss fibers, highly efficient detectors, and quantum repeaters. Quantum repeaters, analogous to classical repeaters, aim to extend the range of QKD by overcoming photon loss, but their development is complex and requires entanglement swapping and quantum memory. Current long-distance QKD systems often rely on trusted nodes, which are secure locations where the key is relayed, but these introduce a potential vulnerability.

Beyond BB84, several other QKD protocols have been developed, each with its own strengths and weaknesses. E91, proposed by Artur Ekert, utilizes entangled photons to establish a secure key, offering a different approach to security based on Bell’s theorem and the violation of Bell inequalities. Measurement-device-independent QKD (MDI-QKD) addresses the vulnerability of detector side-channels by removing the need for Alice and Bob to trust their measurement devices. Continuous-variable QKD (CV-QKD) utilizes continuous variables, such as the amplitude and phase of light, rather than discrete photon polarization states, offering potential advantages in terms of compatibility with existing telecommunication infrastructure. Each protocol presents unique engineering challenges and trade-offs in terms of key rate, distance, and security assumptions.

The integration of QKD with classical cryptographic techniques is crucial for building practical and robust communication systems. QKD is not intended to replace classical encryption algorithms entirely but rather to provide a secure method for distributing cryptographic keys. These keys can then be used with symmetric encryption algorithms, such as AES, to encrypt and decrypt the actual data being transmitted. This hybrid approach combines the security of QKD with the efficiency and scalability of classical cryptography. Furthermore, QKD can be integrated with quantum error correction codes to mitigate the effects of noise and imperfections in the quantum channel, enhancing the reliability and performance of the system.

The development of quantum networks, where multiple users can securely communicate using QKD, represents a significant step towards realizing the full potential of quantum cryptography. These networks require quantum switches and routers to direct quantum signals between users, as well as quantum memories to store and process quantum information. Building a large-scale quantum network is a complex undertaking, requiring significant advances in quantum technology and network infrastructure. Several research groups and companies are actively working on developing prototype quantum networks, demonstrating the feasibility of secure quantum communication over longer distances and with multiple users. The Chinese Micius satellite, launched in 2016, has been used to demonstrate QKD over intercontinental distances, showcasing the potential of satellite-based quantum communication.

The future of quantum cryptography extends beyond key distribution to encompass other quantum cryptographic primitives, such as quantum digital signatures and quantum secret sharing. Quantum digital signatures offer enhanced security compared to classical digital signatures, as they are resistant to forgery attacks even with unlimited computational power. Quantum secret sharing allows a secret to be divided among multiple parties, such that no single party can reconstruct the secret on their own, but they can collectively do so. These advanced quantum cryptographic primitives promise to further enhance the security and privacy of communication and data storage in the quantum era. The ongoing research and development in quantum cryptography are paving the way for a more secure and resilient communication infrastructure in the future.

Quantum Teleportation Principles Explored

Quantum teleportation, despite its name, does not involve the transfer of matter, but rather the instantaneous transfer of a quantum state from one location to another, leveraging the principles of quantum entanglement and classical communication. This process relies on a pre-shared entangled pair of particles – particles whose quantum states are linked regardless of the distance separating them. When a quantum state needs to be teleported, the sender performs a Bell state measurement on the particle carrying the unknown quantum state and one particle of the entangled pair. This measurement collapses the entanglement and yields classical information – two bits – which are then communicated to the receiver via a classical channel. The receiver, using this classical information, then performs a specific unitary transformation on their particle of the entangled pair, reconstructing the original quantum state. It is crucial to understand that the original quantum state is destroyed at the sender’s location during the Bell state measurement, adhering to the no-cloning theorem, which prohibits the creation of identical copies of an unknown quantum state.

The feasibility of quantum teleportation is fundamentally rooted in the principles of quantum entanglement, a phenomenon where two or more particles become linked in such a way that they share the same fate, no matter how far apart they are. This interconnectedness isn’t due to any physical connection, but rather a correlation in their quantum properties. When one particle is measured, the state of the other is instantly known, regardless of the distance separating them. This instantaneous correlation doesn’t violate special relativity, as it cannot be used to transmit information faster than light; the classical communication channel is still required to complete the teleportation process. The entangled state serves as a resource, enabling the transfer of quantum information, but the actual information transfer is limited by the speed of light due to the classical communication requirement. The creation of high-fidelity entangled pairs is a significant technological challenge in realizing practical quantum teleportation systems.

The Bell state measurement, a critical component of quantum teleportation, projects the two particles involved onto one of four maximally entangled states, known as Bell states. These states are specific superpositions of the two particles’ quantum properties, and the outcome of the measurement is probabilistic. The two bits of classical information obtained from the Bell state measurement specify which of the four Bell states was observed, and this information is essential for the receiver to correctly reconstruct the original quantum state. Without the classical communication of these two bits, the receiver cannot determine the appropriate unitary transformation to apply, and the teleportation process fails. The accuracy of the Bell state measurement directly impacts the fidelity of the teleported quantum state; any errors in the measurement will introduce errors in the reconstructed state.

The role of classical communication in quantum teleportation is often misunderstood. While quantum entanglement enables the instantaneous correlation between particles, it cannot be used to transmit information faster than light. The classical communication channel is necessary to convey the two bits of information resulting from the Bell state measurement, which are essential for the receiver to reconstruct the original quantum state. This classical communication is limited by the speed of light, effectively setting a limit on the speed of quantum teleportation. The bandwidth and reliability of the classical channel are crucial factors in determining the overall performance of a quantum teleportation system. Any errors or delays in the classical communication will directly impact the fidelity and speed of the teleportation process.

The no-cloning theorem, a fundamental principle of quantum mechanics, is central to understanding why quantum teleportation doesn’t violate the laws of physics. This theorem states that it is impossible to create an identical copy of an unknown quantum state. Quantum teleportation doesn’t create a copy of the original state; instead, it transfers the state from one location to another, destroying the original state in the process. This destruction of the original state is a direct consequence of the Bell state measurement, which collapses the quantum state. The no-cloning theorem ensures that quantum information cannot be duplicated, preserving the fundamental principles of quantum mechanics. Any attempt to violate the no-cloning theorem would lead to logical paradoxes and inconsistencies in the quantum framework.

Practical implementations of quantum teleportation face significant technological challenges, primarily related to maintaining the fragile quantum states of the particles involved. Quantum states are highly susceptible to decoherence, a process where interactions with the environment cause the quantum information to be lost. Maintaining coherence requires isolating the quantum particles from external disturbances, which is extremely difficult to achieve in practice. Furthermore, generating and distributing high-fidelity entangled pairs over long distances is a major hurdle. Current quantum teleportation experiments typically rely on optical fibers or free space, both of which introduce losses and decoherence. Developing more robust quantum communication channels and error correction techniques is crucial for realizing practical quantum teleportation systems.

Despite these challenges, quantum teleportation has been experimentally demonstrated over increasing distances, with recent experiments achieving teleportation over hundreds of kilometers using satellite-based quantum communication. These experiments represent significant progress towards realizing a quantum internet, a network that would enable secure communication and distributed quantum computing. While widespread adoption of quantum teleportation is still years away, the potential benefits are immense, ranging from secure communication networks to advanced quantum sensors and distributed quantum computers. Continued research and development in quantum communication and quantum technologies are essential for unlocking the full potential of quantum teleportation.

Early Quantum Computing Architectures

Early quantum computing architectures faced significant hurdles in translating the theoretical potential of quantum mechanics into functional hardware. Initial designs, largely conceptual in the 1980s and early 1990s, explored various physical systems as potential qubits – the quantum analogue of classical bits. These included trapped ions, superconducting circuits, and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) systems. The challenge wasn’t simply creating a quantum system, but maintaining quantum coherence – the delicate superposition and entanglement necessary for computation – for a sufficient duration to perform meaningful operations. Decoherence, caused by interactions with the environment, rapidly destroys this quantum state, limiting the complexity of calculations. Early architectures, like those based on NMR, suffered from scalability issues; while demonstrating quantum algorithms, they were limited to a small number of qubits due to signal attenuation and spectral crowding, hindering their practical application beyond proof-of-concept experiments.

Trapped ion systems emerged as a promising early architecture due to their relatively long coherence times and high fidelity control. Ions, individually suspended and controlled using electromagnetic fields, possess well-defined energy levels that can serve as qubit states. Early implementations, such as those pioneered by David Wineland’s group at NIST, utilized laser cooling and trapping techniques to isolate and manipulate ions. However, scaling these systems presented considerable engineering challenges. Entangling multiple ions required precise control of their collective motion, and maintaining stable traps for a large number of ions proved difficult. Furthermore, the need for individual addressing of each ion, often achieved through focused laser beams, introduced complexity and limited the connectivity between qubits, impacting the efficiency of quantum algorithms. The initial architectures were limited by the speed of laser control and the difficulty of creating complex ion arrangements.

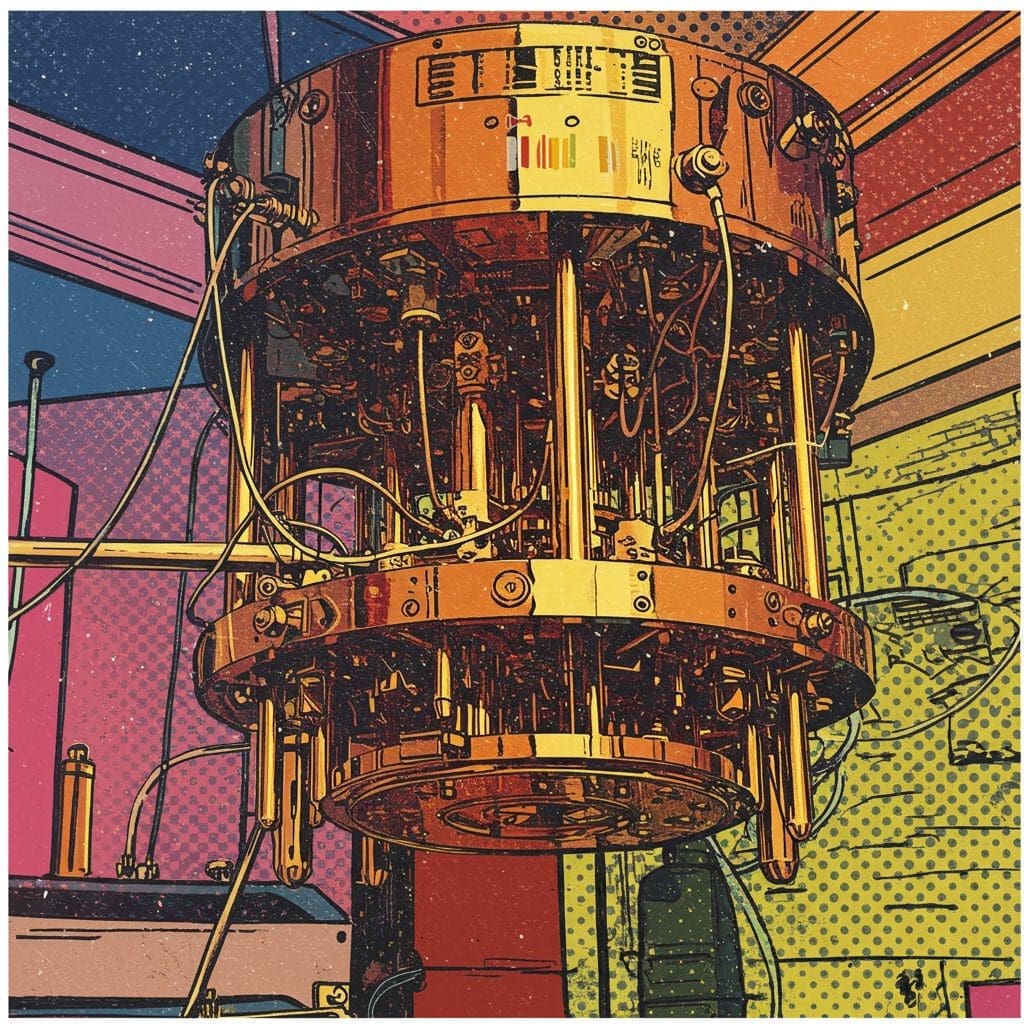

Superconducting circuits offered an alternative approach, leveraging the principles of Josephson junctions to create artificial atoms with quantized energy levels. These circuits, fabricated using microfabrication techniques, allowed for greater control over qubit parameters and potentially higher scalability compared to trapped ions. Early superconducting qubit designs, such as charge qubits and flux qubits, demonstrated the feasibility of creating and manipulating qubits on a chip. However, these early designs were also susceptible to decoherence, primarily due to the interaction of qubits with electromagnetic noise and defects in the superconducting materials. Achieving coherence times long enough for complex computations required careful shielding, filtering, and material purification. The initial designs also suffered from low fidelity control and limited connectivity between qubits, hindering their ability to implement complex quantum algorithms.

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) quantum computing, while demonstrating early success in implementing simple quantum algorithms, faced fundamental limitations that prevented it from becoming a viable large-scale architecture. NMR utilizes the nuclear spins of atoms as qubits, manipulating them using radio frequency pulses. Early NMR experiments successfully demonstrated the implementation of Deutsch’s algorithm and Grover’s algorithm with a few qubits. However, the signal strength decreases exponentially with the number of qubits, making it impractical to scale beyond a handful of qubits. The signal-to-noise ratio becomes exceedingly poor, rendering the computation unreliable. Furthermore, the need for precise control over the magnetic fields and the limited connectivity between nuclear spins posed significant challenges. The inherent limitations of NMR prevented it from becoming a competitive architecture for large-scale quantum computing.

Topological quantum computing, an approach gaining traction in the late 1990s and early 2000s, proposed a fundamentally different architecture aimed at overcoming the decoherence problem. This approach utilizes exotic states of matter known as anyons, which exhibit non-Abelian exchange statistics. The idea is to encode quantum information in the braiding of these anyons, creating qubits that are inherently protected from local perturbations. The braiding operations, representing quantum gates, are topologically protected, meaning they are robust against decoherence. However, realizing these anyonic states in physical systems proved to be extremely challenging. The search for suitable materials and the development of techniques to manipulate and control anyons remain active areas of research. Early theoretical proposals and limited experimental demonstrations highlighted the potential of this approach, but significant hurdles remain before it can become a practical architecture.

Variations on these early architectures also emerged, including quantum dots and cavity quantum electrodynamics. Quantum dots, semiconductor nanocrystals exhibiting quantum mechanical properties, offered potential for scalability and integration with existing microfabrication techniques. However, maintaining coherence in quantum dots proved challenging due to interactions with the surrounding environment and defects in the material. Cavity quantum electrodynamics utilized the interaction between atoms and photons confined within a resonant cavity to enhance quantum effects and create qubits. While demonstrating promising results in controlling individual atoms, scaling these systems to a large number of qubits presented significant engineering challenges. These alternative approaches, while offering unique advantages, faced similar hurdles in achieving the necessary coherence times and scalability for practical quantum computation.

The limitations of these early architectures spurred ongoing research into materials science, control systems, and error correction techniques. Error correction, a crucial aspect of quantum computing, aims to mitigate the effects of decoherence and other errors by encoding quantum information in a redundant manner. Early error correction codes, while theoretically promising, required a significant overhead in terms of the number of physical qubits needed to represent a single logical qubit. This overhead further exacerbated the scalability challenges faced by early quantum computing architectures. The development of more efficient error correction codes and fault-tolerant quantum computing techniques remains a critical area of research for realizing practical quantum computation.

Superconducting Qubits And Coherence Times

Superconducting qubits represent a prominent physical realization within the pursuit of scalable quantum computation, leveraging the macroscopic quantum phenomena exhibited by superconducting circuits. These qubits are typically fabricated using Josephson junctions, non-linear circuit elements enabling the creation of quantized energy levels that serve as the computational states |0⟩ and |1⟩. The performance of superconducting qubits is critically determined by their coherence times – the duration for which a qubit maintains quantum superposition and entanglement, essential for executing quantum algorithms. Several factors contribute to decoherence, including dielectric loss, flux noise, and cosmic ray interactions, all of which introduce unwanted interactions with the qubit environment and lead to the collapse of the quantum state. Minimizing these noise sources and optimizing qubit design are paramount to extending coherence times and improving the fidelity of quantum operations.

The coherence of superconducting qubits is often characterized by two primary time scales: T1 (energy relaxation time) and T2 (dephasing time). T1 represents the time it takes for a qubit to lose its excitation energy to the environment, effectively transitioning from the |1⟩ state to the |0⟩ state. T2, on the other hand, describes the loss of phase coherence between the |0⟩ and |1⟩ states, even without energy loss. While T1 is fundamentally limited by energy dissipation, T2 can be shorter due to various dephasing mechanisms, including fluctuations in the qubit’s energy levels caused by environmental noise. Achieving long T1 and T2 times is crucial for performing complex quantum computations, as the number of operations that can be reliably executed is directly proportional to these coherence parameters. Recent advancements in materials science and circuit design have led to significant improvements in both T1 and T2 times, paving the way for more powerful quantum processors.

Significant research focuses on mitigating decoherence through improved qubit design and materials. One approach involves utilizing materials with lower dielectric loss, reducing the dissipation of energy and extending T1 times. Another strategy involves shielding qubits from external electromagnetic noise, minimizing fluctuations in their energy levels and enhancing T2 times. Furthermore, advanced fabrication techniques are employed to create qubits with higher uniformity and reproducibility, reducing variations in their properties and improving their overall performance. Topological protection, a more advanced concept, aims to encode quantum information in non-local degrees of freedom, making it inherently robust against local perturbations and extending coherence times dramatically. While topological qubits remain a significant technological challenge, they represent a promising pathway towards fault-tolerant quantum computation.

The pursuit of longer coherence times is not solely limited to hardware improvements; sophisticated quantum error correction codes are also essential. These codes encode quantum information redundantly across multiple physical qubits, enabling the detection and correction of errors that inevitably occur during computation. While error correction introduces overhead in terms of qubit requirements, it is considered a necessary component for building scalable and reliable quantum computers. Different error correction codes have varying levels of complexity and performance, and the choice of code depends on the specific characteristics of the qubits and the expected error rates. Furthermore, the implementation of error correction requires precise control over qubit interactions and measurements, adding another layer of complexity to the overall system.

Recent advancements in superconducting qubit technology have demonstrated coherence times exceeding hundreds of microseconds, a substantial improvement over earlier generations of qubits. These improvements have been achieved through a combination of materials optimization, circuit design innovations, and advanced fabrication techniques. For example, utilizing high-purity aluminum and sapphire substrates has significantly reduced dielectric loss and extended T1 times. Furthermore, implementing 3D circuit architectures has enabled tighter integration of qubits and control circuitry, reducing signal delays and improving control fidelity. These advancements have enabled the demonstration of increasingly complex quantum algorithms and the exploration of new quantum computing paradigms.

Despite these significant advancements, maintaining coherence remains a major challenge in superconducting qubit technology. Environmental noise, such as cosmic rays and electromagnetic interference, continues to limit coherence times and introduce errors. Furthermore, imperfections in qubit fabrication and control circuitry can also contribute to decoherence. Addressing these challenges requires a multi-faceted approach, including improved shielding, advanced materials, and sophisticated control techniques. Moreover, developing new qubit designs that are inherently more robust to noise is an active area of research. Exploring alternative qubit modalities, such as transmons with optimized parameters or fluxonium qubits with enhanced coherence, may also offer promising pathways towards longer coherence times.

The interplay between coherence times and gate fidelities is crucial for achieving practical quantum computation. While long coherence times are essential for executing complex algorithms, high-fidelity quantum gates are necessary to minimize errors during each operation. Improving both coherence times and gate fidelities simultaneously is a significant technological challenge, as many optimization strategies for one parameter can negatively impact the other. For example, increasing qubit isolation to reduce noise can also decrease qubit coupling strength, hindering the implementation of two-qubit gates. Therefore, a holistic approach to qubit design and control is required, balancing the need for long coherence with the need for high-fidelity operations.

Trapped Ion Quantum Computing Advances

Trapped ion quantum computing represents a leading modality in the pursuit of scalable quantum computation, distinguished by its high fidelity and long coherence times. The fundamental principle involves confining individual ions—electrically charged atoms—using electromagnetic fields. These trapped ions serve as qubits, the quantum equivalent of classical bits, with their internal energy levels representing the 0 and 1 states. Manipulation of these qubits is achieved through precisely tuned laser pulses or microwave radiation, enabling the execution of quantum gates and algorithms. A key advantage of trapped ions lies in their natural uniformity; being identical particles, they exhibit consistent behavior, reducing sources of error in computations. Furthermore, the strong Coulomb interaction between ions facilitates entanglement, a crucial quantum phenomenon enabling complex computations beyond the capabilities of classical computers.

The architecture of trapped ion quantum computers varies, with two primary approaches: linear ion traps and microfabricated surface traps. Linear Paul traps utilize radiofrequency and static electric fields to confine ions in a linear chain, allowing for relatively long interaction times and straightforward control. However, scaling these systems to larger numbers of qubits presents challenges related to ion addressing and crosstalk. Microfabricated surface traps, on the other hand, offer greater scalability and integration potential, enabling the creation of two-dimensional arrays of qubits. These traps utilize intricate electrode patterns etched onto a chip to create localized potential wells for ion confinement. While fabrication complexities exist, surface traps offer a pathway towards building modular quantum processors with thousands or even millions of qubits. The choice of trap architecture depends on the specific application and desired level of scalability.

Quantum error correction is paramount in realizing fault-tolerant quantum computation, and trapped ion systems are well-suited for implementing various error correction codes. Due to the inherent fragility of quantum states, qubits are susceptible to decoherence and gate errors. Error correction codes encode quantum information across multiple physical qubits, creating redundancy that allows for the detection and correction of errors without destroying the encoded information. Trapped ion systems benefit from high-fidelity single-qubit and two-qubit gates, which are essential for implementing complex error correction protocols. Furthermore, the all-to-all connectivity afforded by Coulomb interactions between ions simplifies the implementation of certain error correction codes, such as surface codes, which are considered promising candidates for large-scale quantum computation.

Recent advancements in trapped ion technology have focused on improving qubit coherence times and gate fidelities. Coherence time refers to the duration for which a qubit maintains its quantum state before decoherence occurs. Extending coherence times is crucial for performing complex quantum algorithms that require numerous gate operations. Researchers have achieved significant progress by employing techniques such as sympathetic cooling, where ions of different species are co-trapped, and utilizing isotopic purification to reduce magnetic field noise. Gate fidelity, which measures the accuracy of quantum gate operations, has also been substantially improved through optimized laser pulse shaping and precise control of ion motion. These advancements have pushed the performance of trapped ion qubits closer to the threshold required for fault-tolerant quantum computation.

A significant challenge in scaling trapped ion quantum computers lies in the efficient control and addressing of individual qubits. As the number of qubits increases, the complexity of controlling each ion independently grows exponentially. Researchers are exploring various techniques to address this challenge, including segmented traps, where each qubit resides in a separate potential well, and individual ion addressing using focused laser beams or microwave radiation. Another approach involves utilizing photonic interconnects to distribute control signals and entanglement between different modules of a quantum processor. These modular architectures offer a pathway towards building large-scale quantum computers by connecting multiple smaller quantum processors.

Beyond hardware advancements, significant progress has been made in the development of quantum control software and algorithms tailored for trapped ion systems. Quantum compilers translate high-level quantum algorithms into sequences of gate operations that can be executed on a specific quantum processor. These compilers must account for the unique characteristics of trapped ion qubits, such as their limited connectivity and susceptibility to noise. Researchers are also developing novel quantum algorithms that are particularly well-suited for implementation on trapped ion systems, leveraging their strengths in areas such as quantum simulation and optimization. The integration of advanced software and algorithms is crucial for unlocking the full potential of trapped ion quantum computers.

The field of trapped ion quantum computing is rapidly evolving, with ongoing research focused on addressing the remaining challenges and realizing the promise of scalable quantum computation. Future directions include exploring new trap designs, developing more robust error correction codes, and improving the integration of quantum hardware and software. While significant hurdles remain, the progress made in recent years demonstrates the viability of trapped ion technology as a leading platform for building powerful quantum computers capable of solving problems beyond the reach of classical computers. The continued investment in research and development is expected to accelerate the pace of innovation and bring us closer to the era of practical quantum computation.

Photonic Quantum Computing Potential

Photonic quantum computing utilizes photons – fundamental particles of light – as qubits, the basic units of quantum information. This approach differs significantly from more established platforms like superconducting circuits or trapped ions, offering distinct advantages and challenges. The inherent properties of photons, such as their lack of charge and weak interaction with matter, minimize decoherence – the loss of quantum information due to environmental interactions. Maintaining coherence for extended periods is crucial for performing complex quantum computations, and photons naturally excel in this regard, potentially enabling larger and more reliable quantum systems. However, efficiently generating, manipulating, and detecting single photons remains a significant technological hurdle, requiring sophisticated optical components and precise control over light sources and detectors.

The creation of stable and scalable photonic qubits relies on various physical implementations. One prominent method involves encoding quantum information in the polarization of single photons, where horizontal and vertical polarization states represent the logical 0 and 1. Another approach utilizes time-bin encoding, where the qubit state is defined by the arrival time of a photon within a specific time window. Furthermore, spatial modes of light, such as different paths a photon can take through an optical circuit, can also serve as qubits. Each encoding scheme presents unique advantages and disadvantages in terms of ease of implementation, coherence time, and compatibility with quantum gates. The choice of encoding scheme significantly impacts the overall architecture and performance of a photonic quantum computer.

Quantum gates, the fundamental building blocks of quantum circuits, are implemented in photonic systems using optical elements that manipulate the quantum state of photons. Linear optical elements, such as beam splitters and waveplates, can perform certain quantum gates deterministically. However, creating universal quantum gates – gates capable of implementing any quantum computation – requires nonlinear optical interactions, which are inherently weak in most materials. Researchers are exploring various techniques to enhance nonlinear interactions, including using materials with high nonlinear optical coefficients, confining light in nanoscale structures, and utilizing squeezed states of light. The development of efficient and scalable quantum gates remains a central challenge in photonic quantum computing.

A key advantage of photonic quantum computing lies in its potential for room-temperature operation. Unlike superconducting qubits, which require extremely low temperatures to function, photons interact weakly with their environment and can maintain coherence at room temperature. This simplifies the engineering requirements and reduces the cost and complexity of building and operating a quantum computer. However, achieving high-fidelity quantum operations at room temperature requires precise control over the optical components and minimization of noise sources. Furthermore, the detectors used to measure the quantum state of photons must be highly sensitive and efficient, even at room temperature.

Scalability is a major consideration for any quantum computing platform, and photonic systems face unique challenges in this regard. Generating and manipulating large numbers of single photons requires complex optical circuits and precise alignment of optical components. Losses in optical elements and detectors can significantly reduce the fidelity of quantum computations. Researchers are exploring various architectures to address these challenges, including integrated photonic circuits, which combine multiple optical components on a single chip. Integrated photonics offers the potential to reduce the size, cost, and complexity of photonic quantum computers while improving their scalability and performance.

The development of efficient single-photon sources and detectors is crucial for realizing practical photonic quantum computers. Ideal single-photon sources should emit photons on demand, with high probability and indistinguishability. Various techniques are used to generate single photons, including spontaneous parametric down-conversion, quantum dots, and nitrogen-vacancy centers in diamond. Single-photon detectors must be highly sensitive, with low dark count rates and high detection efficiency. Superconducting nanowire single-photon detectors (SNSPDs) are currently the most widely used type of single-photon detector, offering high performance and sensitivity. However, SNSPDs require cryogenic cooling, adding to the complexity and cost of the system.

Beyond the technological hurdles, photonic quantum computing offers unique capabilities for specific applications. The natural compatibility of photons with optical fiber networks makes them well-suited for quantum communication and distributed quantum computing. Photonic quantum computers can also excel in simulating quantum systems, such as molecules and materials, due to their ability to efficiently represent and manipulate quantum states. Furthermore, the inherent parallelism of photonic circuits allows for the simultaneous processing of multiple quantum states, potentially leading to significant speedups for certain computational tasks. The development of specialized photonic quantum algorithms and architectures tailored to specific applications will be crucial for unlocking the full potential of this promising technology.

Quantum Error Correction Challenges

Quantum error correction (QEC) presents a formidable challenge to the realization of practical quantum computers, stemming from the inherent fragility of quantum information. Unlike classical bits, which are discrete and robust against minor disturbances, qubits leverage superposition and entanglement, making them exceptionally susceptible to noise and decoherence. These disturbances, originating from interactions with the environment, can introduce errors in quantum computations, rapidly destroying the delicate quantum states necessary for processing information. The no-cloning theorem prohibits simply copying qubits to detect and correct errors, necessitating innovative approaches that circumvent this fundamental limitation. Consequently, QEC schemes rely on encoding a single logical qubit – the unit of quantum information we want to protect – into multiple physical qubits, creating redundancy that allows for the detection and correction of errors without directly measuring the encoded quantum state, which would collapse the superposition.

The primary difficulty in QEC lies in the nature of quantum errors themselves. Classical bits experience bit-flip errors, where a 0 becomes a 1 or vice versa. Qubits, however, are susceptible to both bit-flip and phase-flip errors, and, crucially, arbitrary combinations of these, known as general errors. Correcting general errors requires more complex QEC codes and a significantly larger number of physical qubits per logical qubit. The earliest QEC codes, such as the Shor code, offered protection against arbitrary errors but demanded a substantial overhead – nine physical qubits to encode one logical qubit. Subsequent codes, like surface codes, have reduced this overhead, but still require thousands of physical qubits to achieve fault-tolerant quantum computation, where the error rate of the logical qubit is sufficiently low to allow for long and complex computations. The resource demands are not merely in qubit count, but also in the precision of quantum gates and the fidelity of qubit measurements.

A significant hurdle in implementing QEC is the threshold theorem. This theorem states that fault-tolerant quantum computation is possible only if the error rate of the physical qubits is below a certain threshold. Above this threshold, errors will accumulate faster than they can be corrected, rendering the computation unreliable. Determining this threshold is a complex task, dependent on the specific QEC code, the type of errors present in the system, and the architecture of the quantum computer. Current quantum hardware is still far from meeting these stringent requirements, with error rates often exceeding the threshold for many promising QEC codes. Furthermore, achieving the necessary precision in quantum gates and measurements is a considerable engineering challenge, requiring precise control over individual qubits and minimizing unwanted interactions with the environment.

The implementation of QEC also introduces significant overhead in terms of quantum resources and computational complexity. Encoding and decoding quantum information requires a network of quantum gates and measurements, adding to the overall runtime of the computation. Furthermore, the process of error detection and correction requires continuous monitoring of the qubits, which can introduce additional noise and decoherence. The complexity of QEC schemes scales rapidly with the number of qubits, making it challenging to implement them on large-scale quantum computers. Efficient decoding algorithms are crucial for minimizing the overhead associated with QEC, and ongoing research is focused on developing algorithms that can handle the complexity of decoding large codes in real-time.

Beyond the technical challenges of implementing QEC, there are also fundamental limitations imposed by the laws of physics. The no-communication theorem, a consequence of quantum mechanics, prohibits the use of entanglement for faster-than-light communication. This theorem also implies that it is impossible to perfectly correct all errors in a quantum system, as any attempt to do so would require accessing information about the system that is not available through local measurements. Consequently, QEC schemes can only reduce the error rate of a logical qubit, but cannot eliminate it entirely. The ultimate limit on the fidelity of a quantum computation is therefore determined by the fundamental laws of physics, as well as the practical limitations of the hardware and software used to implement it.

The development of topological quantum codes represents a promising avenue for overcoming some of the challenges associated with QEC. These codes, such as surface codes and color codes, encode quantum information in non-local degrees of freedom, making them more robust against local noise. The errors in topological codes are typically localized, meaning that they affect only a small number of qubits, and can be corrected without disturbing the encoded quantum information. However, implementing topological codes requires complex qubit connectivity and precise control over qubit interactions, posing significant engineering challenges. Furthermore, the decoding algorithms for topological codes can be computationally intensive, requiring significant resources to implement in real-time.

Recent research has focused on developing more efficient QEC codes and decoding algorithms, as well as exploring new hardware architectures that are better suited for implementing QEC. This includes investigating the use of error-biased quantum codes, which are designed to suppress certain types of errors, and developing fault-tolerant quantum gates that are less susceptible to noise. Furthermore, researchers are exploring the use of machine learning techniques to optimize QEC performance and develop adaptive decoding algorithms that can adjust to changing noise conditions. The pursuit of practical QEC remains a central challenge in the field of quantum computing, and continued progress in this area is essential for realizing the full potential of this transformative technology.

NISQ Era And Algorithm Development

The current phase of quantum computing is characterized as the Noisy Intermediate-Scale Quantum (NISQ) era, a period defined by quantum devices with a limited number of qubits—typically ranging from tens to a few hundred—and susceptible to significant errors stemming from environmental noise, imperfect control, and decoherence. This contrasts sharply with the theoretical ideal of fault-tolerant quantum computers requiring thousands of stable, error-corrected qubits for complex computations. The limitations of NISQ devices necessitate the development of algorithms specifically tailored to exploit the available quantum resources while mitigating the impact of noise. These algorithms often prioritize shallow circuit depths—minimizing the number of quantum gate operations—as error rates accumulate with each gate, rendering deep circuits unreliable. The focus is therefore on identifying computational tasks where even imperfect quantum computations can offer an advantage over classical algorithms, even if not a definitive exponential speedup.

Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs) represent a prominent algorithmic approach for the NISQ era. VQAs combine the strengths of quantum and classical computation by employing a hybrid approach. A quantum computer prepares a parameterized quantum state, and measurements are performed on this state to estimate expectation values of certain observables. These expectation values are then fed into a classical optimization algorithm, which adjusts the parameters of the quantum state to minimize or maximize the expectation value, effectively training the quantum circuit to solve a specific problem. This iterative process continues until a satisfactory solution is found. Examples of VQAs include the Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) for finding the ground state energy of molecules and the Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA) for solving combinatorial optimization problems. The effectiveness of VQAs relies heavily on the choice of ansatz—the parameterized quantum circuit—and the classical optimizer used for parameter updates.

The development of quantum algorithms for machine learning is another active area of research within the NISQ context. Quantum machine learning aims to leverage quantum computation to accelerate or improve classical machine learning algorithms. Several quantum algorithms have been proposed for tasks such as classification, regression, and clustering. Quantum Support Vector Machines (QSVMs) and quantum neural networks are examples of algorithms that attempt to exploit quantum phenomena like superposition and entanglement to enhance machine learning performance. However, demonstrating a practical quantum advantage in machine learning remains challenging, as the overhead associated with encoding classical data into quantum states and extracting results can often outweigh the potential speedups. Furthermore, the performance of quantum machine learning algorithms is highly sensitive to the quality of the quantum hardware and the choice of appropriate quantum feature maps.

Error mitigation techniques are crucial for extracting meaningful results from NISQ devices. These techniques do not correct errors in the strict sense but rather aim to reduce their impact on the final outcome. Several error mitigation strategies have been developed, including zero-noise extrapolation, probabilistic error cancellation, and symmetry verification. Zero-noise extrapolation involves running the quantum circuit with different levels of artificially added noise and then extrapolating the results to the zero-noise limit. Probabilistic error cancellation attempts to estimate and cancel out the effects of known error sources. Symmetry verification exploits known symmetries of the problem to identify and discard erroneous results. The effectiveness of error mitigation techniques depends on the specific error model and the characteristics of the quantum hardware.

The limitations of current quantum hardware also drive research into alternative quantum computing architectures beyond the superconducting qubit platform. Trapped ions, neutral atoms, photonic qubits, and topological qubits are all being actively explored as potential candidates for building scalable and fault-tolerant quantum computers. Each architecture has its own strengths and weaknesses in terms of qubit coherence, connectivity, and scalability. Trapped ions offer long coherence times and high fidelity gate operations but suffer from limited connectivity and scalability challenges. Photonic qubits offer room-temperature operation and high connectivity but require complex and efficient single-photon sources and detectors. Topological qubits, based on exotic states of matter, promise inherent robustness against decoherence but are still in the early stages of development.

The development of quantum compilers and software tools is essential for bridging the gap between high-level quantum algorithms and the physical constraints of NISQ hardware. Quantum compilers translate abstract quantum programs into a sequence of physical gate operations that can be executed on a specific quantum device. This process involves optimizing the circuit for minimal gate count, circuit depth, and qubit connectivity. Software tools also provide functionalities for quantum circuit simulation, error analysis, and performance benchmarking. The optimization of quantum compilers is a complex task, as it must account for the unique characteristics of each quantum hardware platform and the limitations of NISQ devices.

The exploration of quantum algorithms beyond those directly inspired by classical counterparts is gaining momentum. Algorithms tailored to the specific strengths of quantum computation, such as quantum simulation of many-body systems and quantum optimization problems with unique quantum constraints, are being investigated. Quantum annealing, while not a universal quantum algorithm, offers a potential advantage for solving certain optimization problems. Furthermore, the development of quantum algorithms for solving problems in areas such as materials science, drug discovery, and financial modeling is attracting significant research interest. The identification of novel quantum algorithms that can demonstrably outperform classical algorithms remains a key challenge in the field.

Quantum Machine Learning Applications

Quantum machine learning (QML) represents an emerging interdisciplinary field exploring the potential synergy between quantum computing and machine learning. Classical machine learning algorithms, while powerful, face limitations when dealing with exponentially large datasets or complex feature spaces. Quantum algorithms offer the possibility of accelerating certain machine learning tasks by leveraging quantum phenomena like superposition and entanglement. However, it’s crucial to understand that not all machine learning problems are suitable for quantum acceleration; the benefits are most pronounced for specific algorithms and data structures. The core idea revolves around encoding data into quantum states and utilizing quantum operations to perform computations that are intractable for classical computers, potentially leading to faster training times and improved model accuracy for certain tasks.

Several quantum algorithms have been adapted or designed specifically for machine learning applications. Quantum Support Vector Machines (QSVMs), for instance, utilize quantum feature maps to transform data into higher-dimensional quantum spaces, potentially enabling the identification of complex patterns that are difficult to discern classically. Quantum Principal Component Analysis (QPCA) offers a potential speedup in dimensionality reduction, a crucial step in many machine learning pipelines. Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) and Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA) are being explored for optimization problems inherent in training machine learning models, although their practical advantage remains an area of active research. It is important to note that the realization of these algorithms is heavily dependent on the development of fault-tolerant quantum computers, which are still years away from widespread availability.

The application of QML extends to various domains, including image recognition, natural language processing, and financial modeling. In image recognition, quantum convolutional neural networks (QCNNs) are being investigated as a potential alternative to classical CNNs, aiming to exploit quantum parallelism to accelerate feature extraction. In natural language processing, quantum algorithms could potentially improve tasks like sentiment analysis and machine translation by efficiently processing high-dimensional text data. Financial modeling could benefit from quantum algorithms for portfolio optimization and risk management, leveraging quantum speedups to analyze complex financial instruments and market data. However, the current limitations of quantum hardware and the need for specialized quantum algorithms pose significant challenges to the practical implementation of QML in these domains.

A key challenge in QML lies in the efficient encoding of classical data into quantum states. This process, known as quantum feature mapping, can be computationally expensive and may negate any potential speedup gained from quantum algorithms. Different encoding strategies exist, such as amplitude encoding, angle encoding, and basis encoding, each with its own trade-offs in terms of computational cost and expressiveness. The choice of encoding strategy depends on the specific data type and the quantum algorithm being used. Furthermore, the scalability of quantum feature mapping is a major concern, as the number of qubits required to encode a large dataset can quickly become prohibitive. Research is ongoing to develop more efficient and scalable quantum encoding techniques.

Hybrid quantum-classical algorithms represent a promising approach to overcome the limitations of current quantum hardware. These algorithms combine the strengths of both quantum and classical computation, offloading computationally intensive tasks to the quantum computer while relying on classical algorithms for pre- and post-processing. Variational Quantum Algorithms (VQAs), such as VQE and QAOA, fall into this category, utilizing a classical optimization loop to train a quantum circuit. This approach allows researchers to explore the potential benefits of QML even with noisy intermediate-scale quantum (NISQ) devices, which have limited qubit counts and coherence times. However, the performance of hybrid algorithms is highly sensitive to the choice of quantum circuit architecture and optimization parameters.

Despite the potential benefits, several practical hurdles remain before QML can become a mainstream technology. The development of fault-tolerant quantum computers is a major challenge, as maintaining the coherence of qubits is extremely difficult. Furthermore, the scarcity of quantum computing resources and the lack of standardized quantum programming languages and tools hinder the widespread adoption of QML. The need for specialized expertise in both quantum computing and machine learning also poses a barrier to entry. Addressing these challenges requires significant investment in quantum hardware, software, and education. The development of robust error correction techniques and the creation of user-friendly quantum programming tools are crucial steps towards realizing the full potential of QML.

The current landscape of QML is characterized by active research and experimentation. While the field is still in its early stages, significant progress is being made in developing new quantum algorithms, improving quantum hardware, and exploring potential applications. The focus is shifting from theoretical exploration to practical implementation, with researchers increasingly focusing on developing hybrid quantum-classical algorithms that can be run on NISQ devices. The long-term impact of QML remains uncertain, but the potential benefits are significant enough to warrant continued investment and research. The convergence of quantum computing and machine learning could revolutionize various fields, leading to breakthroughs in areas such as drug discovery, materials science, and artificial intelligence.

Topological Quantum Computing Concepts

Topological quantum computing represents a departure from conventional quantum computing approaches by leveraging the principles of topology to encode and manipulate quantum information. Unlike traditional qubits which are susceptible to environmental noise and decoherence due to their reliance on individual particle states, topological qubits are encoded in the non-local properties of exotic quasiparticles known as anyons. These anyons, existing in specifically engineered two-dimensional systems, acquire unique quantum states when exchanged – a process that alters the wavefunction of the system in a way that is robust against local perturbations. This inherent robustness stems from the fact that the information isn’t stored in the precise location of a particle, but in the topology of its trajectory around other particles, making it significantly less vulnerable to decoherence. The braiding of these anyons, analogous to weaving strands of hair, forms the basis for performing quantum computations, with different braiding patterns corresponding to different quantum gates.

The realization of topological quantum computing hinges on the existence and control of anyons, which are not bosons or fermions but obey different exchange statistics. Specifically, Majorana zero modes, a type of non-Abelian anyon, are considered prime candidates for building topological qubits. These modes emerge as quasiparticle excitations in certain superconducting materials and semiconductor nanowires with strong spin-orbit coupling and proximity to a conventional superconductor. The non-Abelian nature of Majorana zero modes is crucial; it means that exchanging two such modes doesn’t simply multiply the wavefunction by a phase factor (as with bosons or fermions), but rather performs a more complex transformation, allowing for the implementation of universal quantum gates. Creating and manipulating these modes requires precise control over material properties and external fields, presenting significant experimental challenges.

The physical implementation of topological qubits is not limited to Majorana zero modes; other types of anyons, such as parafermions, are also being investigated. Parafermions exhibit fractional exchange statistics and can be realized in various condensed matter systems, including fractional quantum Hall states and certain topological insulators. While Majorana zero modes have received considerable attention due to their relatively simple properties and potential for realization in hybrid superconducting circuits, parafermionic qubits offer the possibility of encoding more complex quantum information and performing more sophisticated quantum operations. The choice of which type of anyon to pursue depends on the specific material platform and the desired level of control and scalability.

A key advantage of topological quantum computing is its potential for fault tolerance. Because the information is encoded in the topology of the system, it is protected against local errors that would typically destroy quantum coherence in conventional qubits. This inherent robustness significantly reduces the need for complex error correction schemes, which are essential for building large-scale quantum computers. However, topological protection is not absolute. Non-local errors, such as those caused by cosmic rays or macroscopic defects in the material, can still affect the qubits. Therefore, some level of error correction may still be necessary, but it is expected to be much simpler and more efficient than that required for conventional qubits.

The fabrication of topological qubits presents substantial materials science and engineering challenges. Creating the necessary two-dimensional systems with the required level of purity and control over material properties is extremely difficult. Hybrid structures, combining different materials with complementary properties, are often used to engineer the desired topological states. For example, semiconductor nanowires with strong spin-orbit coupling can be proximity-coupled to a conventional superconductor to induce superconductivity and create Majorana zero modes. Precise control over the interface between these materials is crucial for achieving the desired topological properties. Furthermore, scaling up the number of qubits while maintaining their coherence and controllability is a major hurdle.

Despite the challenges, significant progress has been made in recent years. Researchers have demonstrated the creation and manipulation of Majorana zero modes in various experimental setups, including semiconductor nanowires, topological insulators, and superconducting circuits. While these demonstrations are still far from a fully functional quantum computer, they provide proof-of-principle evidence that topological qubits are feasible. Ongoing research focuses on improving the coherence and controllability of these qubits, as well as developing new materials and fabrication techniques to scale up the number of qubits. The development of robust control schemes and efficient readout mechanisms is also crucial for realizing a practical topological quantum computer.

The potential benefits of topological quantum computing extend beyond simply building more robust qubits. The unique properties of anyons could also enable the development of new quantum algorithms and protocols that are impossible to implement on conventional quantum computers. For example, topological quantum computation could be used to simulate complex quantum systems with greater efficiency and accuracy. Furthermore, the inherent fault tolerance of topological qubits could pave the way for building quantum computers that are capable of solving problems that are currently intractable for even the most powerful classical computers. This could have profound implications for fields such as materials science, drug discovery, and artificial intelligence.

Quantum Sensing And Metrology Gains

Quantum sensing and metrology represent a significant advancement beyond classical measurement techniques, leveraging quantum mechanical phenomena to achieve sensitivities unattainable by conventional methods. These gains stem from the ability of quantum systems to exist in superposition and exhibit entanglement, properties that allow for the precise measurement of physical quantities like magnetic fields, electric fields, gravity, time, and temperature. Classical sensors are fundamentally limited by the standard quantum limit (SQL), which arises from the inherent uncertainty in measuring conjugate variables; quantum sensors, however, can surpass this limit by exploiting quantum correlations and reducing measurement noise. This improvement isn’t merely incremental; it represents a potential paradigm shift in fields ranging from medical diagnostics to materials science and fundamental physics research, enabling the detection of previously undetectable signals and the characterization of systems with unprecedented precision.

The enhancement in sensitivity offered by quantum sensors is directly linked to the concept of entanglement and squeezing. Entanglement, a uniquely quantum phenomenon, creates correlations between particles such that the state of one instantaneously influences the state of another, regardless of the distance separating them. This correlation can be harnessed to reduce the noise in measurements, effectively amplifying the signal. Quantum squeezing, a technique used to manipulate quantum states, reduces the uncertainty in one variable at the expense of increased uncertainty in its conjugate variable, allowing for more precise measurements of the chosen variable. Nitrogen-vacancy (NV) centers in diamond are a prime example; these defects act as sensitive magnetometers, with their spin states manipulated and read out using microwave and optical techniques, achieving sensitivities orders of magnitude greater than classical magnetometers. This is achieved by carefully controlling the quantum state of the NV center and minimizing decoherence, the loss of quantum information due to interactions with the environment.