The race to build a quantum computer capable of outperforming even the most powerful conventional machines is hitting a surprising roadblock: noise. While recent experiments hint at the possibility of “quantum advantage,” new research reveals that the very imperfections plaguing today’s quantum hardware dramatically simplify the task for classical computers attempting to simulate them. A team led by Thomas Schuster at Caltech has discovered that noise effectively limits the computational space, allowing classical algorithms to mimic quantum processes with far less power than previously thought – potentially confining true quantum supremacy to a narrow “Goldilocks zone” of qubit numbers and error rates. Understanding these limitations is crucial as scientists strive to build genuinely powerful and scalable quantum computers.

Quantum Advantage and Current Limitations

The pursuit of quantum advantage – demonstrating a quantum computer’s ability to outperform classical computers – faces significant hurdles due to inherent noise in current systems. Recent research highlights that achieving this advantage isn’t simply a matter of increasing qubit count, but rather operating within a constrained “Goldilocks zone.” Noise effectively “kills off” computational paths within a quantum circuit, allowing classical algorithms to simulate the quantum process by focusing only on the remaining, dominant paths. Google’s 2019 experiment with 53 superconducting qubits, while a landmark attempt, suffered from a high error rate – a 99.8% noise level and only 0.2% fidelity – illustrating this challenge. While quantum error-correction offers a potential solution, it demands substantial qubit scaling beyond current capabilities. Consequently, researchers are revisiting classical simulation algorithms, leveraging the impact of noise to define the boundaries within which a noisy, uncorrected quantum computer might genuinely achieve computational superiority.

Noise’s Impact on Quantum Computation

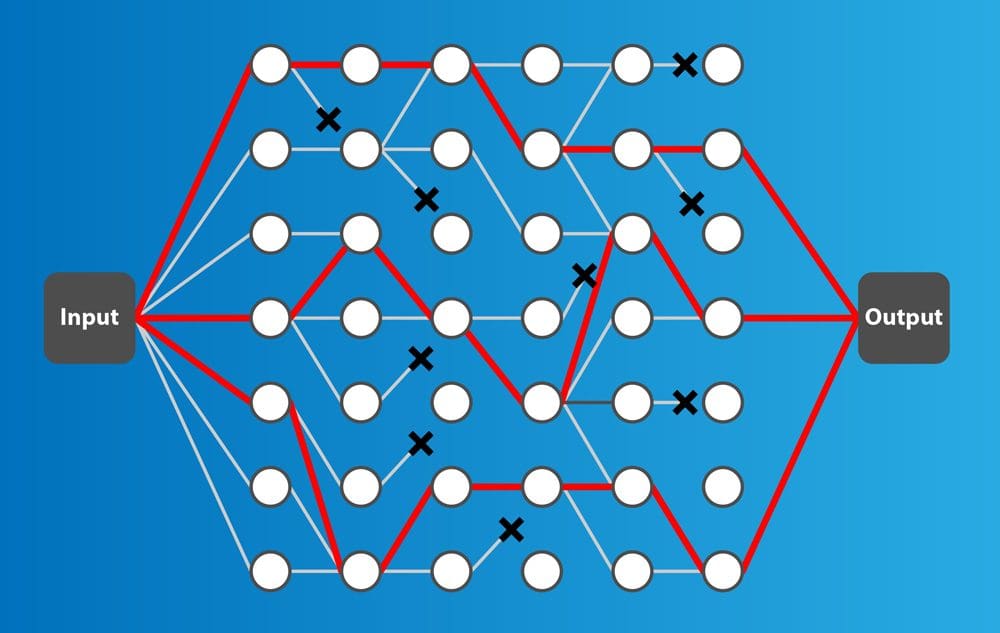

Noise presents a fundamental obstacle to achieving quantum advantage, significantly limiting the scope of computations current quantum computers can outperform classical ones. Research revisiting classical simulation algorithms reveals that uncorrected noise effectively “kills off” certain computational pathways – known as Pauli paths – within a quantum circuit. This reduction in viable paths allows classical algorithms to simulate the quantum computation by focusing only on the remaining, prominent paths, dramatically reducing the computational burden. As demonstrated by analyses of experiments like Google’s 2019 53-qubit processor (which achieved a fidelity of only 0.2% amidst 99.8% noise), high error rates curtail the complexity quantum systems can reliably handle. Consequently, achieving quantum advantage without robust error correction may be confined to a narrow “Goldilocks zone”—a specific range of qubit numbers where quantum effects aren’t overwhelmed by noise, yet aren’t so complex as to defeat classical simulation. Understanding these constraints is critical as researchers strive to demonstrate practical quantum computation.

Pauli Paths and Classical Simulation

The feasibility of achieving quantum advantage is increasingly understood through the lens of “Pauli paths” and their impact on classical simulation. Quantum computations can be visualized as evolving along multiple trajectories—these Pauli paths—starting from input states and culminating in measurable outputs. However, noise within current quantum computers doesn’t impact all paths equally; instead, it effectively “kills off” many, reducing the computational landscape. This selective elimination is crucial because it directly constrains the complexity a classical algorithm needs to simulate the quantum computation. Researchers are revisiting classical simulation algorithms based on Feynman path integrals, recognizing that only a subset of these Pauli paths – those surviving the noise – need to be computed to accurately reproduce the quantum circuit’s output. Consequently, the potential for quantum advantage may be limited by this reduction in necessary computations, existing within a “Goldilocks zone” where the remaining paths are complex enough to be challenging for classical computers, but not so numerous as to negate any advantage.

Qubit Scaling and Error Correction

Current limitations in quantum computing stem from the delicate balance between qubit scaling and the pervasive issue of error correction. While achieving “quantum advantage” – outperforming classical computers – is a primary goal, noisy qubits significantly restrict experimental possibilities. Research indicates a “Goldilocks zone” exists; too few qubits lack the complexity for advantage, while too many, without correction, become easily simulated by classical algorithms. Google’s 2019 experiment with 53 superconducting qubits, though groundbreaking, demonstrated high error rates – a 99.8% noise level and 0.2% fidelity – highlighting the challenge. Though quantum error correction offers a solution, it demands a substantial increase in qubit count, exceeding current capabilities. Consequently, researchers are revisiting classical simulation algorithms, leveraging Feynman path integrals to understand if quantum advantage is attainable without fully correcting for errors, and to define the boundaries within which near-term quantum devices can genuinely outperform their classical counterparts.