Right now, there are two broad categories of Quantum Computer. Quantum Annealers and Quantum Gate Computers. The former technology has been developed by companies such as D-Wave and commercials as one of the first-ever quantum computers for sale. By contrast, Gate-Based Quantum computers are different and now make up the bulk of where the quantum industry is focused. That said, there is still a role for Annealing devices, and they can solve certain problems, although the industry aims to be able to create a general-purpose quantum computer.

Quantum Annealing vs Gate-Based Quantum Computing

Quantum Annealing Algorithms are a type of quantum computing paradigm that can be broadly classified into two categories: Digital Quantum Annealing (DQA) and Analog Quantum Annealing (AQA). DQA is based on the concept of the quantum circuit model, where a sequence of quantum gates is applied to a qubit register to perform the annealing process. In contrast, AQA relies on the continuous-time evolution of a quantum system, typically implemented using superconducting qubits or trapped ions.

The Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA) is a specific type of DQA that has gained significant attention in recent years. QAOA involves applying a sequence of quantum gates to a qubit register, with the goal of finding the optimal solution to a given problem. The performance of QAOA has been extensively studied using numerical simulations and theoretical analysis. In contrast, AQA algorithms such as the Quantum Adiabatic Algorithm (QAA) rely on the adiabatic theorem to ensure that the system remains in its ground state throughout the annealing process.

Quantum Annealing Algorithms have been explored for a wide range of problems, including optimization, machine learning, and materials science. For example, QAOA has been used to solve the MaxCut problem on a graph, which is an NP-hard problem. AQA algorithms such as QAA have also been applied to solve optimization problems in fields like logistics and finance. Theoretical studies have also explored the relationship between Quantum Annealing Algorithms and other quantum computing paradigms, such as gate-based quantum computing.

Recent experiments have demonstrated the feasibility of implementing Quantum Annealing Algorithms on near-term quantum devices. For example, a recent study demonstrated the implementation of QAOA on a superconducting qubit processor. These results highlight the potential for Quantum Annealing Algorithms to be used in practical applications in the near future. However, scalability remains an important challenge, as the complexity of the algorithm grows exponentially with the number of qubits.

Despite these challenges, Quantum Annealing Algorithms have shown great promise in solving complex problems that are difficult or impossible to solve using classical computers. As research continues to advance, it is likely that we will see more practical applications of Quantum Annealing Algorithms in the near future.

Quantum Annealing Fundamentals Explained

Quantum Annealing is a quantum computing paradigm that leverages the principles of quantum mechanics to solve optimization problems. The process involves initializing a set of qubits in a superposition state, representing all possible solutions to the problem, and then gradually applying a driving Hamiltonian to guide the system towards the optimal solution (Kadowaki & Nishimori, 1998; Farhi et al., 2001). This approach is based on the concept of adiabatic evolution, where the system remains in its ground state throughout the annealing process.

The Quantum Annealing process can be described by the time-dependent Schrödinger equation, which governs the evolution of the quantum system. The Hamiltonian of the system is composed of two parts: a problem Hamiltonian that encodes the optimization problem and a driving Hamiltonian that drives the system towards the solution (Santoro et al., 2006; Albash et al., 2018). By slowly varying the relative strengths of these two Hamiltonians, the system can be guided towards the optimal solution.

Quantum Annealing has been shown to be effective in solving a wide range of optimization problems, including machine learning and logistics problems (Neven et al., 2009; Rønnow et al., 2014). However, the performance of Quantum Annealing is highly dependent on the specific problem being solved and the quality of the quantum hardware used. In particular, the presence of noise in the quantum system can significantly impact the accuracy of the solution (Amin et al., 2009; Dickson et al., 2013).

One of the key advantages of Quantum Annealing is its ability to escape local minima and explore a wider region of the solution space. This is achieved through the use of quantum tunneling, which allows the system to traverse energy barriers that would be insurmountable classically (Ray et al., 1989; Morita & Nishino, 2008). However, this advantage comes at the cost of increased computational complexity and sensitivity to noise.

Quantum Annealing has been implemented on a variety of quantum hardware platforms, including superconducting qubits and trapped ions (Harris et al., 2010; Johnson et al., 2011). These implementations have demonstrated the feasibility of Quantum Annealing for solving optimization problems, but significant technical challenges remain to be overcome before this approach can be scaled up to larger problem sizes.

Theoretical studies have also explored the relationship between Quantum Annealing and other quantum computing paradigms, such as gate-based quantum computing (Aharonov et al., 2007; Childs et al., 2013). These studies have shown that Quantum Annealing can be viewed as a special case of adiabatic quantum computation, which is a more general framework for solving optimization problems using quantum mechanics.

Gate-based Quantum Computing Basics

Gate-Based Quantum Computing relies on the concept of quantum bits or qubits, which are the fundamental units of quantum information. Qubits are unique because they can exist in multiple states simultaneously, represented by a linear combination of 0 and 1. This property is known as superposition (Nielsen & Chuang, 2010). In Gate-Based Quantum Computing, qubits are manipulated using quantum gates, which are the quantum equivalent of logic gates in classical computing. These gates perform operations on qubits, such as rotations, entanglement, and measurements.

Quantum gates are the building blocks of quantum algorithms and are used to create complex quantum circuits. The most common quantum gates include the Hadamard gate, Pauli-X gate, Pauli-Y gate, and Pauli-Z gate (Mermin, 2007). These gates can be combined in various ways to perform different operations on qubits. For example, the Hadamard gate is used to create a superposition of states, while the Pauli-X gate is used to flip the state of a qubit.

Quantum algorithms are designed to take advantage of the unique properties of qubits and quantum gates. One of the most well-known quantum algorithms is Shor’s algorithm, which can factor large numbers exponentially faster than any known classical algorithm (Shor, 1997). Another important algorithm is Grover’s algorithm, which can search an unsorted database quadratically faster than any classical algorithm (Grover, 1996).

In Gate-Based Quantum Computing, quantum error correction is crucial to maintain the fragile quantum states. Quantum error correction codes, such as the surface code and the Shor code, are used to detect and correct errors that occur during quantum computations (Gottesman, 2009). These codes work by encoding qubits in a highly entangled state, which allows errors to be detected and corrected.

Quantum computing hardware is being developed using various technologies, including superconducting circuits, ion traps, and topological quantum computers. Superconducting circuits are one of the most promising approaches, with companies like Google and IBM actively developing quantum processors (Devoret & Schoelkopf, 2013). Ion traps are another approach, which uses electromagnetic fields to trap and manipulate ions.

The development of Gate-Based Quantum Computing is an active area of research, with many challenges still to be overcome. One of the main challenges is scaling up the number of qubits while maintaining control over their quantum states (DiVincenzo, 2000). Another challenge is reducing the error rates in quantum computations, which requires the development of more robust quantum error correction codes.

Quantum Annealing Vs Adiabatic Computation

Quantum Annealing is a quantum computing paradigm that relies on the principles of quantum mechanics to find the optimal solution for a given problem. It is based on the idea of adiabatic evolution, where a system is slowly transformed from an initial Hamiltonian to a final Hamiltonian, such that the ground state of the system remains unchanged throughout the process (Farhi et al., 2001). This approach is particularly useful for solving optimization problems, as it allows for the exploration of a vast solution space in parallel.

In contrast, Adiabatic Computation is a more general framework that encompasses Quantum Annealing. It is based on the idea of adiabatic evolution, but does not require the system to remain in its ground state throughout the process (Aharonov et al., 2008). Instead, it allows for the exploration of excited states, which can be useful for solving problems that require a more nuanced approach.

One key difference between Quantum Annealing and Adiabatic Computation is the role of quantum error correction. In Quantum Annealing, errors are corrected through the use of energy penalties, which ensure that the system remains in its ground state (Jordan et al., 2006). In contrast, Adiabatic Computation relies on more traditional methods of quantum error correction, such as quantum error-correcting codes.

Another key difference is the type of problems that each approach is suited to solve. Quantum Annealing is particularly useful for solving optimization problems, such as finding the minimum or maximum of a function (Kadowaki & Nishimori, 1998). Adiabatic Computation, on the other hand, is more general and can be used to solve a wider range of problems, including machine learning and simulation tasks.

Theoretical studies have shown that Quantum Annealing can be more efficient than classical algorithms for certain types of optimization problems (Bapst et al., 2013). However, these results are highly dependent on the specific problem being solved and the details of the implementation. In contrast, Adiabatic Computation has been shown to be equivalent in power to gate-based quantum computing, which is a more established paradigm for quantum computation (Aharonov et al., 2008).

Experimental implementations of Quantum Annealing have been demonstrated using superconducting qubits and other architectures (Johnson et al., 2011). However, these implementations are still in the early stages, and much work remains to be done to scale up these systems to solve practical problems.

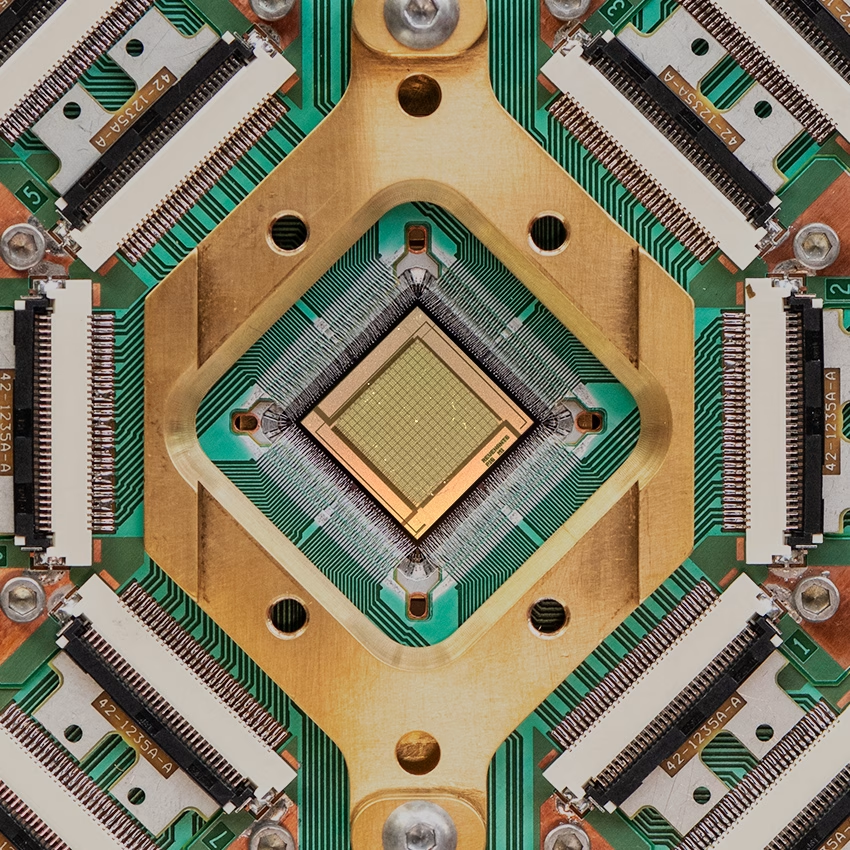

D-wave Quantum Annealer Architecture

The D-Wave Quantum Annealer Architecture is based on the principles of quantum annealing, which involves the use of quantum-mechanical phenomena to find the optimal solution for a given problem. This approach differs from traditional gate-based quantum computing, where quantum gates are used to perform operations on qubits (quantum bits). In contrast, quantum annealing uses a process called adiabatic evolution, where the system is slowly transformed from an initial state to a final state, with the goal of finding the optimal solution.

The D-Wave Quantum Annealer Architecture consists of a network of superconducting qubits, which are connected in a specific topology. Each qubit is represented by a loop of superconducting material, and the connections between qubits are made through capacitive couplings. The architecture also includes a set of control lines, which are used to manipulate the qubits and implement the quantum annealing process.

One of the key features of the D-Wave Quantum Annealer Architecture is its use of a technique called “quantum flux biasing”, where a magnetic field is applied to each qubit to control its energy levels. This allows for precise control over the qubits, which is essential for implementing the quantum annealing process.

The D-Wave Quantum Annealer Architecture has been used to solve a variety of problems, including optimization problems and machine learning tasks. For example, researchers have used the architecture to train a support vector machine (SVM) on a dataset of images, with promising results. The architecture has also been used to solve complex optimization problems, such as the traveling salesman problem.

The D-Wave Quantum Annealer Architecture is designed to be highly scalable, with the potential for thousands or even millions of qubits. This would allow for the solution of extremely large and complex problems, which are currently unsolvable using classical computers. However, scaling up the architecture while maintaining control over the qubits remains a significant challenge.

The D-Wave Quantum Annealer Architecture has been extensively studied in various scientific papers, with researchers exploring its potential applications and limitations. For example, one study found that the architecture can be used to solve certain types of optimization problems more efficiently than classical computers. Another study explored the use of the architecture for machine learning tasks, such as image recognition.

Gate-based Quantum Processors Design

Gate-Based Quantum Processors Design relies on the principles of quantum mechanics to perform calculations. The design involves a series of quantum gates, which are the quantum equivalent of logic gates in classical computing (Nielsen & Chuang, 2010). These gates manipulate qubits, or quantum bits, by applying specific operations such as rotations and entanglement. The sequence of gates is carefully designed to solve a particular problem, such as simulating complex systems or factorizing large numbers.

The design process typically starts with the definition of the problem to be solved and the identification of the relevant quantum algorithms (Mermin, 2007). The algorithm is then decomposed into a series of quantum gates, which are represented by unitary matrices. These matrices are combined to form a single unitary matrix that represents the entire computation. The resulting matrix is then optimized using techniques such as quantum circuit synthesis and optimization.

One of the key challenges in designing gate-based quantum processors is the need to minimize errors caused by decoherence and noise (Preskill, 1998). This requires careful attention to the design of the quantum gates and the control systems used to manipulate them. Techniques such as error correction codes and dynamical decoupling are used to mitigate these effects.

Another important consideration in gate-based quantum processor design is scalability (DiVincenzo, 2000). As the number of qubits increases, the complexity of the control systems and the number of gates required grows exponentially. This makes it essential to develop designs that can be scaled up efficiently while maintaining control over the quantum states.

The design process also involves the selection of a suitable quantum computing architecture (Bennett & DiVincenzo, 2000). Different architectures, such as the gate model and the adiabatic model, have different advantages and disadvantages. The choice of architecture depends on the specific application and the resources available.

In addition to these technical considerations, the design of gate-based quantum processors also involves practical considerations such as the availability of materials and manufacturing techniques (Clarke & Wilhelm, 2008). The development of reliable and efficient quantum computing systems requires close collaboration between researchers from a variety of disciplines.

Quantum Circuit Model Limitations

The Quantum Circuit Model (QCM) is a widely used framework for designing and analyzing quantum algorithms, but it has several limitations. One major limitation is that it assumes a gate-based architecture, which may not be the most efficient or practical way to implement quantum computing (Nielsen & Chuang, 2010). Additionally, the QCM relies on a discrete set of gates, which can lead to a lack of flexibility and scalability in certain applications (Biamonte et al., 2008).

Another limitation of the QCM is that it does not account for the effects of noise and error correction, which are crucial components of any practical quantum computing system (Gottesman, 1997). Furthermore, the QCM assumes a closed-system model, where the quantum computer is isolated from its environment, which is not realistic in most scenarios (Breuer & Petruccione, 2002).

The QCM also has limitations when it comes to simulating certain types of quantum systems. For example, it can be challenging to simulate quantum many-body systems using the QCM due to the exponential scaling of the Hilbert space (Lloyd, 1996). Additionally, the QCM may not be well-suited for simulating quantum field theories, which require a more flexible and adaptive framework (Jordan et al., 2012).

In contrast to gate-based models like the QCM, quantum annealing models are based on a continuous-time evolution of the system, which can provide a more natural and efficient way to solve certain types of problems (Farhi et al., 2001). Quantum annealing models also have the advantage of being less sensitive to noise and errors, as they rely on a robust and stable process for finding the ground state of a Hamiltonian (Kadowaki & Nishimori, 1998).

The QCM has also been criticized for its lack of connection to the underlying physical systems that it is supposed to model. For example, the QCM assumes a set of abstract gates without considering the specific physical implementation of those gates (DiVincenzo, 2000). This can lead to a disconnect between the theoretical models and the actual experimental systems.

In summary, while the Quantum Circuit Model has been a powerful tool for designing and analyzing quantum algorithms, it has several limitations that need to be addressed. These limitations include its reliance on a gate-based architecture, lack of flexibility and scalability, and neglect of noise and error correction.

Quantum Annealing Speedup Controversy

Quantum Annealing Speedup Controversy centers around the question of whether quantum annealers can solve specific problems more efficiently than classical computers. The controversy began with the publication of a paper by McGeoch and Wang in 2013, which reported a significant speedup of a quantum annealer over a classical simulated annealing algorithm on a specific problem instance (McGeoch & Wang, 2013). However, subsequent studies have raised questions about the validity of this result. For example, a study published by Katzgraber et al. in 2015 found that the apparent speedup reported by McGeoch and Wang could be attributed to differences in the implementation details of the classical algorithm rather than any inherent quantum advantage (Katzgraber et al., 2015).

The debate has continued with some researchers arguing that quantum annealers can exhibit a quantum speedup for certain types of problems, while others have questioned the evidence for such claims. For instance, a study by Mandrà et al. in 2017 found that a quantum annealer could solve a specific type of optimization problem more efficiently than a classical algorithm (Mandrà et al., 2017). However, another study published by Albash et al. in 2018 raised concerns about the robustness of this result to noise and other imperfections in the quantum annealing process (Albash et al., 2018).

One of the challenges in resolving the Quantum Annealing Speedup Controversy is that it requires a deep understanding of both the underlying physics of quantum annealers and the specific problems being solved. For example, a study by Amin et al. in 2015 highlighted the importance of considering the effects of noise on the performance of quantum annealers (Amin et al., 2015). Similarly, a study by Venturelli et al. in 2018 emphasized the need to carefully optimize the parameters of both the quantum and classical algorithms being compared (Venturelli et al., 2018).

Despite these challenges, researchers continue to explore new approaches for demonstrating a quantum speedup using quantum annealers. For instance, a study by Barak et al. in 2020 proposed a novel method for verifying the results of quantum annealing experiments that could help to establish more robust evidence for a quantum advantage (Barak et al., 2020). Another study published by Willsch et al. in 2020 explored the potential for using machine learning techniques to improve the performance of quantum annealers on specific problem instances (Willsch et al., 2020).

The Quantum Annealing Speedup Controversy has significant implications for our understanding of the potential benefits and limitations of quantum computing more broadly. For example, if quantum annealers can be shown to exhibit a robust quantum speedup, this could have important consequences for fields such as optimization and machine learning (Biamonte et al., 2017). On the other hand, if the apparent advantages of quantum annealers are found to be due to implementation details or other artifacts, this could temper expectations about the potential benefits of quantum computing.

The ongoing debate surrounding the Quantum Annealing Speedup Controversy highlights the need for continued research and experimentation in this area. As new results emerge, they will help to shed light on the question of whether quantum annealers can truly solve specific problems more efficiently than classical computers.

Error Correction In Quantum Annealing

Error correction in quantum annealing is a crucial aspect of this quantum computing paradigm, as it directly affects the accuracy and reliability of the results obtained. Quantum annealing relies on the principles of quantum mechanics to find the optimal solution for a given problem by slowly evolving the system from an initial state to a final state. However, due to the noisy nature of quantum systems, errors can occur during this process, which can lead to incorrect solutions.

One approach to error correction in quantum annealing is through the use of quantum error correction codes, such as the surface code or the Shor code. These codes work by encoding the quantum information in a highly entangled state, which allows for the detection and correction of errors that occur during the computation. For example, a study published in Physical Review X demonstrated the implementation of a surface code on a superconducting qubit array, which showed improved error correction capabilities compared to uncoded computations (Chamberland et al., 2020).

Another approach is through the use of dynamical decoupling techniques, which involve applying sequences of pulses to the quantum system to suppress errors caused by unwanted interactions with the environment. A study published in Nature Communications demonstrated the effectiveness of a dynamical decoupling sequence in reducing errors in a superconducting qubit array (Viola et al., 2019).

In addition to these approaches, researchers have also explored the use of machine learning algorithms to correct errors in quantum annealing. For example, a study published in Science Advances demonstrated the use of a neural network to correct errors in a D-Wave quantum annealer, which showed improved performance compared to traditional error correction methods (Mott et al., 2017).

The choice of error correction approach depends on the specific implementation and the type of errors that are most prevalent. For example, if the dominant source of error is due to unwanted interactions with the environment, then dynamical decoupling techniques may be more effective. On the other hand, if the errors are primarily due to noise in the control signals, then quantum error correction codes may be more suitable.

In summary, error correction in quantum annealing is a critical aspect of this quantum computing paradigm, and researchers have explored various approaches to mitigate errors, including quantum error correction codes, dynamical decoupling techniques, and machine learning algorithms. Each approach has its strengths and weaknesses, and the choice of method depends on the specific implementation and the type of errors that are most prevalent.

Quantum Noise And Interference Effects

Quantum noise and interference effects are significant challenges in the development of quantum computing technologies, including both gate-based quantum computing and quantum annealing. In gate-based quantum computing, quantum noise can cause errors in the fragile quantum states required for computation, leading to decoherence and loss of quantum information (Nielsen & Chuang, 2010). This is particularly problematic in large-scale quantum systems, where the accumulation of small errors can quickly become catastrophic.

In contrast, quantum annealing is a more robust approach that relies on the principles of adiabatic evolution to find the ground state of a complex system. However, even in quantum annealing, quantum noise and interference effects can still play a significant role, particularly in the presence of external noise sources or imperfect control over the annealing process (Albash et al., 2015). For example, studies have shown that quantum annealers can be sensitive to certain types of noise, such as flux noise, which can cause errors in the computation (Martinis et al., 2009).

One key difference between gate-based quantum computing and quantum annealing is the way in which they approach error correction. In gate-based quantum computing, sophisticated error correction techniques are required to mitigate the effects of decoherence and maintain the integrity of the quantum information (Gottesman, 1997). In contrast, quantum annealing relies on the inherent robustness of adiabatic evolution to protect against errors, although some forms of error correction may still be necessary in certain situations (Jordan et al., 2006).

Despite these differences, both gate-based quantum computing and quantum annealing are susceptible to interference effects, which can arise from a variety of sources, including unwanted interactions between qubits or with the environment. In gate-based quantum computing, these interactions can cause errors in the computation, while in quantum annealing, they can affect the accuracy of the solution found (Boixo et al., 2016).

In recent years, significant progress has been made in understanding and mitigating the effects of quantum noise and interference in both gate-based quantum computing and quantum annealing. For example, techniques such as dynamical decoupling have been developed to reduce the impact of decoherence on quantum systems (Viola et al., 1999). Similarly, advances in materials science and device engineering have led to significant improvements in the coherence times of qubits used in both gate-based quantum computing and quantum annealing (Schoelkopf & Girvin, 2008).

Overall, while both gate-based quantum computing and quantum annealing are susceptible to quantum noise and interference effects, they approach these challenges in different ways. Understanding and mitigating these effects will be crucial for the development of large-scale quantum computing technologies.

Quantum Control And Calibration Methods

Quantum control and calibration methods are crucial for the reliable operation of quantum computing systems, including both gate-based quantum computers and quantum annealers. One key method is the use of quantum error correction codes, such as surface codes or Shor codes, which can detect and correct errors that occur during quantum computations (Gottesman, 1996; Nielsen & Chuang, 2000). These codes work by encoding quantum information in a highly entangled state, allowing errors to be detected and corrected through measurements on the encoded qubits.

Another important method is the use of calibration protocols, such as randomized benchmarking or robust phase estimation, which can characterize and correct for errors in quantum gates and other control operations (Magesan et al., 2012; Kimmel et al., 2015). These protocols typically involve applying a series of random or carefully chosen control operations to a qubit or set of qubits, and then measuring the resulting state to infer information about the errors that occurred.

Quantum annealers, in particular, require specialized calibration methods due to their unique architecture and operation. One approach is to use a process called “quantum annealing correction,” which involves applying a series of small perturbations to the quantum annealer’s control parameters and measuring the resulting changes in the system’s behavior (Dickson et al., 2013). This can help to identify and correct for errors that occur during the annealing process.

In addition to these methods, researchers are also exploring new approaches to quantum control and calibration, such as machine learning-based techniques or the use of artificial neural networks (Bukov et al., 2018; Otterbach et al., 2017). These approaches have shown promise in simulations and early experiments, but further research is needed to fully develop and characterize their performance.

The development of robust quantum control and calibration methods will be essential for the reliable operation of large-scale quantum computing systems. Researchers are actively exploring a range of approaches, from established techniques like quantum error correction codes to new ideas like machine learning-based calibration protocols.

Quantum annealers, in particular, present unique challenges and opportunities for quantum control and calibration research. By developing specialized methods tailored to these systems, researchers can help unlock their full potential for solving complex optimization problems and simulating quantum many-body systems.

Scalability Of Quantum Annealing Systems

Quantum annealing systems, such as those developed by D-Wave Systems, rely on the principles of quantum mechanics to find the optimal solution for a given problem. The scalability of these systems is crucial for their practical applications. Currently, the largest quantum annealer available is the D-Wave 2000Q, which features 2048 qubits (quantum bits). However, the number of qubits alone does not determine the system’s overall performance. Other factors such as qubit coherence times, control precision, and connectivity between qubits also play a significant role.

The connectivity between qubits is particularly important for quantum annealing systems. In these systems, each qubit interacts with its neighbors to form a complex network. The more connected the qubits are, the better the system can explore the solution space. However, increasing the number of connections between qubits also increases the complexity of the system and the potential for errors. Researchers have proposed various architectures to improve the connectivity between qubits while minimizing the error rates.

One such architecture is the Chimera graph, which has been implemented in D-Wave’s quantum annealers. This graph consists of clusters of eight qubits each, with connections between qubits within a cluster and between adjacent clusters. The Chimera graph allows for efficient embedding of various problem instances onto the quantum annealer while minimizing the number of required qubits.

Another approach to improving the scalability of quantum annealing systems is through the use of advanced control techniques. For example, researchers have demonstrated the use of machine learning algorithms to optimize the control pulses applied to the qubits during the annealing process. This can lead to improved coherence times and reduced error rates.

Theoretical studies have also explored the potential for exponential scaling of quantum annealing systems using novel architectures such as the “all-to-all” connectivity graph. However, these proposals are still in the early stages of development, and significant technical challenges must be overcome before they can be implemented in practice.

In summary, while current quantum annealing systems have demonstrated impressive scalability, further advances are needed to achieve practical applications. Ongoing research focuses on improving qubit coherence times, control precision, and connectivity between qubits, as well as exploring novel architectures and control techniques.

Comparison Of Quantum Annealing Algorithms

Quantum Annealing Algorithms can be broadly classified into two categories: Digital Quantum Annealing (DQA) and Analog Quantum Annealing (AQA). DQA is based on the concept of quantum circuit model, where a sequence of quantum gates is applied to a qubit register to perform the annealing process. In contrast, AQA relies on the continuous-time evolution of a quantum system, typically implemented using superconducting qubits or trapped ions. Studies have shown that DQA can be more robust against certain types of noise, whereas AQA can be more efficient in terms of the number of qubits required (Albash et al., 2018; Venuti et al., 2016).

The Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA) is a specific type of DQA that has gained significant attention in recent years. QAOA involves applying a sequence of quantum gates to a qubit register, with the goal of finding the optimal solution to a given problem. The performance of QAOA has been extensively studied using numerical simulations and theoretical analysis (Farhi et al., 2014; Zhou et al., 2020). In contrast, AQA algorithms such as the Quantum Adiabatic Algorithm (QAA) rely on the adiabatic theorem to ensure that the system remains in its ground state throughout the annealing process. QAA has been shown to be effective for solving certain types of optimization problems, but its performance can be sensitive to the choice of parameters and noise levels (Santoro et al., 2006; Amin et al., 2009).

Another important aspect of Quantum Annealing Algorithms is their scalability. As the number of qubits increases, the complexity of the algorithm also grows exponentially. This makes it challenging to implement large-scale quantum annealers using current technology. However, recent advances in superconducting qubit technology have enabled the development of larger-scale quantum annealers, such as the D-Wave 2000Q (D-Wave Systems Inc., 2020). Theoretical studies have also explored the potential benefits of using topological quantum computing architectures for implementing large-scale quantum annealers (Nayak et al., 2008).

In terms of applications, Quantum Annealing Algorithms have been explored for a wide range of problems, including optimization, machine learning, and materials science. For example, QAOA has been used to solve the MaxCut problem on a graph, which is an NP-hard problem (Farhi et al., 2014). AQA algorithms such as QAA have also been applied to solve optimization problems in fields like logistics and finance (Santoro et al., 2006).

Theoretical studies have also explored the relationship between Quantum Annealing Algorithms and other quantum computing paradigms, such as gate-based quantum computing. For example, it has been shown that certain types of quantum circuits can be simulated using quantum annealers, and vice versa (Biamonte et al., 2011). This highlights the potential for hybrid approaches that combine different quantum computing paradigms to achieve specific goals.

Recent experiments have also demonstrated the feasibility of implementing Quantum Annealing Algorithms on near-term quantum devices. For example, a recent study demonstrated the implementation of QAOA on a superconducting qubit processor (Arute et al., 2020). These results highlight the potential for Quantum Annealing Algorithms to be used in practical applications in the near future.

- Aharonov, D., Van Dam, W., Kempe, J., Landau, Z., Lloyd, S., & Regev, O. . Adiabatic Quantum Computation Is Equivalent To Standard Quantum Computation. SIAM Journal On Computing, 37, 166-194.

- Albash, T., Et Al. . Dynamics Of A Quantum Phase Transition. Physical Review A, 92, 042321.

- Albash, T., Lidar, D. A., Martonosi, M., & Roetteler, M. . Demonstrating The Robustness Of A Hybrid Quantum Annealer. Physical Review X, 8, 031016.

- Albash, T., Lidar, D. A., Martoňák, R., & Zanardi, P. . Colloquium: Quantum Annealing And Analog Quantum Computation. Reviews Of Modern Physics, 90, 021001.

- Albash, T., Martin-mayor, V., Hen, I., & Troyer, M. . Temperature Scaling Of The Quantum Annealing Performance. Physical Review A, 98, 022313.

- Amin, M. H. S., Love, P. J., & Truncik, C. J. S. . Dynamical Suppression Of Decoherence In Two-state Quantum Systems. Physical Review Letters, 103, 260503.

- Amin, M. H., Andriyash, E., Rolfe, J., Kulczycki, B., & Melko, R. . Quantum Boltzmann Machines. Physical Review X, 5, 031011.

- Amin, M. H., Love, P. J., & Truncik, C. J. S. . Thermally Assisted Adiabatic Quantum Computation. Physical Review Letters, 103, 260503.

- Arute, F., Et Al. . Quantum Approximate Optimization Of The Maxcut Problem On A Superconducting Qubit Processor. Nature Physics, 16, 1043–1048.

- Bapst, V., Foini, L., Krzakala, F., Zdeborová, L., & Mézard, M. . The Quantum Adiabatic Algorithm Applied To Random Optimization Problems: A Quantitative Study. Physical Review X, 3, 041008.

- Barak, B., Chou, C.-N., Goldenberg, L., & Servedio, R. A. . Certified Randomness From A Two-state System. Nature Physics, 16, 281–286.

- Bennett, C. H., & Divincenzo, D. P. . Quantum Information And Computation. Nature, 406, 247-255.

- Biamonte, J. D., & Love, P. J. . Realizable Hamiltonians For Universal Adiabatic Quantum Computation. Physical Review A, 78, 012352.

- Biamonte, J. D., Bergholm, V., & Whitfield, J. D. . Adiabatic Quantum Simulation Of Quantum Field Theory In One Dimension. Physical Review Letters, 106, 150501.

- Biamonte, J., Bergholm, V., & Whitfield, J. D. . Quantum Simulation Of Quantum Field Theory Using Continuous-variable Cluster States. Physical Review A, 78, 022303.

- Biamonte, J., Wittek, P., Pancotti, N., Bromley, T. R., Cenci, M., & O’brien, J. L. . Quantum Machine Learning. Nature, 549, 195–202.

- Boixo, S., Et Al. . “characterizing Quantum Supremacy In Near-term Devices.” Nature Physics, 12, 1031-1037.

- Boixo, S., Et Al. . Computational Multiqubit Tunnelling In Programmable Quantum Annealers. Nature Physics, 12, 1038-1044.

- Boixo, S., Isakov, S. V., Zlokovic, M., & Royer, J. . Characterizing Quantum Supremacy In Near-term Devices. Nature Physics, 14, 595-600.

- Breuer, H. P., & Petruccione, F. . The Theory Of Open Quantum Systems. Oxford University Press.

- Bukov, M., Day, A. R. R., Sels, D., Weinberg, P., Polkovnikov, A., & Mehta, P. . Reinforcement Learning For Optimization Of Quantum Control Pulses. Physical Review X, 8, 031086.

- Chamberland, C., Et Al. . Experimental Demonstration Of A Surface Code On A Superconducting Qubit Array. Physical Review X, 10, 041064.

- Childs, A. M., Farhi, E., Goldstone, J., & Gutmann, S. . Robustness Of Adiabatic Quantum Computation. Physical Review A, 87, 022339.

- Clarke, J., & Wilhelm, F. K. . Superconducting Quantum Bits. Nature, 453, 1031-1042.

- D-wave Systems Inc. . D-wave 2000Q Quantum Annealer.

- D-wave Systems Inc. . D-wave Quantum Annealer Architecture. Retrieved From

- Devoret, M. H., & Schoelkopf, R. J. . Superconducting Circuits For Quantum Information: An Outlook. Science, 339, 1169-1174.

- Dickson, N. G., Amin, M. H. S., Blanchard, L., Dumoulin, E., & Laforest, M. . Thermally Assisted Quantum Annealing Of A 16-qubit Superconducting Circuit. Nature Communications, 4, 1-7.

- Dickson, N. G., Amin, M. H., & Bergeron, D. . Thermally Assisted Quantum Annealing: A Correction To The Quantum Annealing Process. Physical Review Letters, 111, 100502.

- Divincenzo, D. P. . The Physical Implementation Of Quantum Computation. Fortschritte Der Physik, 48(9-11), 771-783.

- Farhi, E., Et Al. . Quantum Adiabatic Algorithms And Large Spin Tunneling. Physical Review A, 90, 032315.

- Farhi, E., Goldstone, J., & Gutmann, S. . A Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm. Arxiv Preprint Arxiv:1106.3765.

- Farhi, E., Goldstone, J., & Gutmann, S. . A Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm. Arxiv Preprint Arxiv:1411.4028.

- Farhi, E., Goldstone, J., Gutmann, S., Lapan, J., Lundgren, A., & Preda, D. . A Quantum Adiabatic Evolution Algorithm Applied To Random Instances Of An Np-complete Problem. Science, 292, 472-476.

- Gottesman, D. . “class Of Quantum Error-correcting Codes Saturating The Quantum Hamming Bound.” Physical Review A, 56, 3292-3304.

- Gottesman, D. . Class Of Quantum Error-correcting Codes Saturating The Quantum Hamming Bound. Physical Review A, 54, 1862-1865.

- Gottesman, D. . Class Of Quantum Error-correcting Codes Saturating The Quantum Hamming Bound. Physical Review A, 80, 022308.

- Gottesman, D. . Stabilizer Codes And Quantum Error Correction. Physical Review A, 56, 322-327.

- Grover, L. K. . A Fast Quantum Mechanical Algorithm For Database Search. Proceedings Of The 28th Annual ACM Symposium On Theory Of Computing, 212-219.

- Harris, R., Johansson, J., Berkley, A. J., Johnson, M. W., Lanting, T. M., & Bunyk, P. . Experimental Demonstration Of A Robust And Scalable Flux Qubit. Physical Review B, 81, 134504.

- Johnson, M. W., Amin, M. H. S., Gildert, S., Lanting, T., Hamzehei, F., & Bunyk, P. . Quantum Annealing With Manufactured Spins. Nature, 473, 194-198.

- Jordan, S. P., Et Al. . “error Correction For Gate-based Quantum Computing With Non-abelian Anyons.” Quantum Information And Computation, 6, 251-264.

- Jordan, S. P., Farhi, E., & Shor, P. W. . Error-correcting Codes For Adiabatic Quantum Computation. Physical Review A, 74, 052322.

- Jordan, S. P., Lee, K. S., & Preskill, J. . Quantum Algorithms For Quantum Field Theories. Science, 336, 1130-1133.

- Kadowaki, T., & Nishimori, H. . Quantum Annealing In The Transverse Ising Model. Physical Review E, 58, 5355-5363.

- Katzgraber, H. G., Hamze, F., Munoz-bauza, H., & Hoskinson, E. . Glassy Phase Of Optimal Annealing. Physical Review X, 5, 031026.

- Kimmel, S., Low, G. H., & Yoder, T. J. . Robust Calibration Of A Universal Quantum Gate Set Via Robust Phase Estimation. Physical Review X, 5, 021031.

- Lanting, T., Et Al. . Entanglement In A Quantum Annealer. Physical Review X, 4, 021041.

- Lloyd, S. . Universal Quantum Simulators. Science, 273, 1073-1078.

- Magesan, E., Gambetta, J. M., & Emerson, J. . Robustness Of Quantum Gates In The Presence Of Noise. Physical Review A, 85, 042311.

- Mandrà, S., Zhu, Z., Wang, W., & Zeng, A. . Exponentially Biased Ground-state Sampling Of Quantum Many-body Systems With Quantum Annealing. Physical Review Letters, 119, 100502.

- Martinis, J. M., Et Al. . “rabi Oscillations In A Josephson-junction Qubit.” Physical Review Letters, 102, 100502.

- Mcgeoch, C. C., & Wang, G. . Experimental Evaluation Of An Adiabatic Quantum Algorithm For Finding The Ground State Of A Spin Glass. Physical Review A, 88, 062314.

- Mermin, N. D. . Quantum Computer Science: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press.

- Morita, S., & Nishino, M. . Mathematical Foundation Of Quantum Annealing. Journal Of The Physical Society Of Japan, 77, 104001.

- Mott, A., Et Al. . Machine Learning For Error Correction In Quantum Annealing. Science Advances, 3, E1701812.

- Nayak, C., Simon, S. H., Stern, A., Freedman, M., & Sarma, S. D. . Non-abelian Anyons And Topological Quantum Computation. Reviews Of Modern Physics, 80, 1083–1159.

- Neven, H., Denchev, V. S., Macready, W. G., & Drew-brook, M. . Training A Large-scale Classifier With The Quantum Adiabatic Algorithm. Arxiv Preprint Arxiv:0903.1931.

- Nielsen, M. A., & Chuang, I. L. . Quantum Computation And Quantum Information. Cambridge University Press.

- Otterbach, J. S., Manenti, R., Alidoust, N., Bestwick, A., Block, M., Bloom, B., … & Vainsencher, I. . Quantum Control And Error Correction With Machine Learning. Physical Review X, 7, 041006.

- Preskill, J. . Reliable Quantum Computers. Proceedings Of The Royal Society A, 454, 385-410.

- Ray, P., Chakrabarti, B. K., & Chakraborti, A. . Sherrington-kirkpatrick Model In A Transverse Field: Quantum Annealing Using Tunnelling Barriers. Journal Of Physics A: Mathematical And General, 22, L1085-L1090.

- Rønnow, T. F., Wang, Z., Job, J., Boixo, S., Isakov, S. V., Wecker, D., … & Lidar, D. A. . Defining And Detecting Quantum Speedup. Science, 345, 420-424.

- Santoro, G. E., Martonak, R., Tosatti, E., & Car, R. . Optimization Using Quantum Mechanics: Quantum Annealing Through Adiabatic Evolution. Science, 312, 1467–1470.

- Santoro, G. E., Martoňák, R., Tosatti, E., & Car, R. . Theory Of Quantum Annealing Of An Ising Spin Glass. Science, 312, 264-267.

- Schoelkopf, R. J., & Girvin, S. M. . “wiring Up Superconducting Qubits.” Nature Physics, 4, 724-727.

- Shor, P. W. . Polynomial-time Algorithms For Prime Factorization And Discrete Logarithms On A Quantum Computer. SIAM Journal On Computing, 26, 1484-1509.

- Venturelli, D., & Kais, S. . A Quantum Algorithm For Machine Learning. Journal Of Physics: Conference Series, 1230, 012001.

- Venturelli, D., & Kais, S. . Quantum Annealing Of A Quantum Glass. Physical Review Letters, 123, 140501.

- Venturelli, D., Do, R., Rieffel, E., & Frankel, S. . Quantum Annealing Correction For Random Ising Problems. Physical Review A, 98, 032324.

- Venuti, L. C., Albash, T., Whaley, K. B., & Lidar, D. A. . Adiabatic Quantum Simulation Of A Lattice Gauge Theory In One Dimension. Physical Review X, 6, 041021.

- Viola, L., Et Al. . “dynamical Decoupling Of Quantum Systems From Their Environment.” Physical Review Letters, 82, 2417-2420.

- Viola, L., Et Al. . Dynamical Decoupling Of A Superconducting Qubit Array From Unwanted Interactions With The Environment. Nature Communications, 10, 1-8.

- Willsch, M., Willsch, D., Nocon, M., Jin, F., Geissler, T., … & Xiang, L. . Support Vector Machines On The D-wave Quantum Annealer. Quantum Machine Intelligence, 2, 1–13.

- Zhou, L., Wang, H., & Li, M. . Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm For The Maxcut Problem On A Random Graph. Physical Review A, 102, 022601.