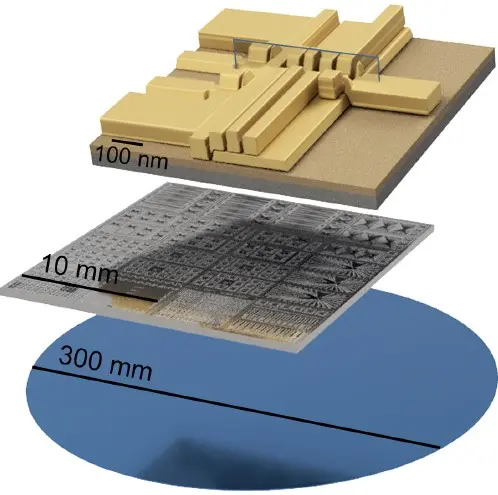

Quantum computers promise to solve problems that are intractable for today’s silicon‑based machines, but turning the idea into a market‑ready product has proved a formidable engineering challenge. The latest development from the Belgian research hub imec and Australian start‑up Diraq marks a turning point: silicon quantum‑dot qubits fabricated with industrial tools now consistently exceed the fidelity thresholds required for practical quantum error correction. In other words, the building blocks of a future quantum processor are no longer confined to specialised cleanrooms; they can be produced in the same factories that make everyday microchips.

From laboratory prototypes to industrial‑grade qubits

The heart of the breakthrough lies in the reproducibility of qubit performance. In earlier experiments, researchers selected the best‑performing devices,so‑called “hero” qubits,making it difficult to gauge how many chips would meet the stringent criteria in a production run. The new study sidestepped this bias by measuring randomly chosen devices from a batch fabricated on imec’s 300 mm spin‑qubit platform. The results were striking: single‑ and two‑qubit gate operations consistently achieved fidelities above 99 %, while state‑preparation and measurement steps reached over 99.9 %. These figures are comfortably above the 99 % benchmark that allows quantum error‑correcting codes to suppress logical errors to acceptable levels.

The high fidelity is the product of several engineered improvements. First, the quantum dots are defined in a silicon metal‑oxide‑semiconductor (MOS) stack that has been optimised for low electrical noise. Second, the silicon channel is isotopically enriched with ^28Si, reducing magnetic noise from residual nuclear spins that otherwise perturb the electron spin qubits. Finally, the fabrication process inherits the precision and uniformity of CMOS foundry techniques, ensuring that each qubit experiences the same electrostatic environment. Together, these advances demonstrate that industrial manufacturing can deliver the low‑noise, high‑fidelity qubits once thought exclusive to academic cleanrooms.

Scaling the silicon quantum advantage

Achieving high fidelity is only the first step toward a useful quantum computer; the real test is whether the process can be scaled to millions of qubits at a reasonable cost. The collaboration between Diraq and imec shows that the answer is yes. By leveraging the existing silicon micro‑chip supply chain, Diraq can tap into the economies of scale that have made the global semiconductor industry a powerhouse. The company’s roadmap envisions a single chip containing millions of qubits, each fabricated with the same 300 mm process that underpins today’s processors. Because the production line is already designed to minimise defects and maximise yield, the incremental cost of adding quantum layers is far lower than building a bespoke quantum fabrication facility.

Moreover, the industrial approach promises a clear path to utility‑scale quantum computing, where the performance benefits outweigh the cost. Diraq’s CEO Andrew Dzurak highlighted that the partnership validates a commercially viable model: high‑fidelity qubits produced at scale can bring the cost per logical qubit down to the level required for real‑world applications such as drug discovery, optimisation, and secure communications. As the industry moves from prototype to production, the same tools that enable billions of transistors per wafer will now produce quantum processors capable of tackling problems beyond the reach of classical algorithms.

Beyond the laboratory: implications for the wider ecosystem

The achievement has ramifications that extend beyond the immediate companies involved. For the first time, silicon MOS‑based quantum‑dot devices fabricated with industrial methods have matched, and in some respects surpassed, the performance of academic hero qubits. This parity removes a long‑standing barrier that has kept quantum hardware in the realm of research labs. With reproducible, high‑fidelity qubits available from a mass‑production line, other players,foundries, system integrators, and software developers,can begin to design end‑to‑end quantum solutions.

The next frontier lies in further noise suppression. The research team suggests that additional isotopic enrichment of the silicon channel could push fidelities even higher, potentially reaching the 99.99 % level that would make error‑correction overheads negligible. Coupled with advances in qubit connectivity and error‑correction codes, such improvements could shorten the time to a fault‑tolerant quantum computer by several years. Meanwhile, the industrial model offers a flexible platform for exploring different qubit architectures, such as hybrid spin,photon systems, without abandoning the proven CMOS infrastructure.

In the broader context of global technology competition, the collaboration signals that Europe and Australia are serious contenders in the quantum race. While the United States and China continue to invest heavily in quantum research, the ability to produce quantum chips at scale using mature semiconductor processes gives imec and Diraq a distinct competitive edge. It also underscores the importance of cross‑disciplinary partnerships,between academia, industry, and government,to translate scientific breakthroughs into commercial realities.

Looking ahead

The convergence of high‑fidelity qubits and industrial manufacturing marks a watershed moment for quantum computing. It demonstrates that the technology can move beyond proof‑of‑concept experiments into the realm of scalable production. For investors, policymakers, and technologists, the message is clear: silicon‑based quantum processors are no longer a speculative dream but a tangible product on the verge of mass deployment. As the industry builds on this foundation, the next decade will likely witness the emergence of quantum‑enhanced applications that reshape medicine, logistics, and cryptography, ushering in an era where the extraordinary power of quantum mechanics is harnessed by the very factories that built the digital world.