A new theory proposes that the interiors of Uranus and Neptune, our solar system’s unique ice giants, are layered. A water-rich layer is separated from a deeper layer of hot, high-pressure carbon, nitrogen, and hydrogen. This configuration explains the planets’ unusual magnetic fields, which the Voyager 2 mission discovered in the late 1980s.

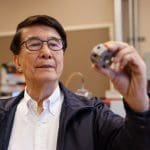

According to Burkhard Militzer, a planetary scientist at the University of California, Berkeley, these immiscible layers prevent convection, resulting in disorganized magnetic fields unlike Earth’s. Militzer used computer simulations and machine learning to model the behavior of atoms under extreme pressure and temperature conditions, finding that layers naturally form as the atoms are heated and compressed.

His research, supported by the National Science Foundation, provides a new understanding of these enigmatic planets and could be confirmed by future NASA missions or laboratory experiments.

Unraveling the Mysteries of Uranus and Neptune’s Magnetic Fields

For decades, scientists have been puzzled by the unusual magnetic fields of Uranus and Neptune, the two ice giants in our solar system. Unlike Earth, which has a strong dipole magnetic field, these planets exhibit disorganized magnetic fields that defy explanation. Now, thanks to cutting-edge computer simulations and machine learning techniques, researchers have made a groundbreaking discovery that sheds light on the internal structure of these enigmatic worlds.

Layered Interiors: The Key to Understanding Magnetic Fields

Burkhard Militzer, a physicist from UC Berkeley, has led the charge in unraveling the mystery. Using advanced computer models, he simulated the behavior of hundreds of atoms under extreme pressure and temperature conditions, mimicking those found in the interiors of Uranus and Neptune. To his surprise, the simulations revealed that the atoms naturally separate into distinct layers: a water-rich layer and a hydrocarbon-rich layer.

The Water-Rich Layer: Convection and Magnetic Fields

Militzer’s research suggests that the upper, water-rich layer is convective, meaning it can move and generate disorganized magnetic fields. This layer is thought to be around 5,000 miles thick in Uranus and similarly thick in Neptune. The convection process creates the observed magnetic field patterns, which are unlike those found on Earth.

The Hydrocarbon-Rich Layer: Stability and No Convection

In contrast, the lower, hydrocarbon-rich layer is non-convective, meaning it remains stable and does not generate large-scale magnetic fields. This layer is also approximately 5,000 miles thick in both Uranus and Neptune. The stratified structure of this layer, composed of carbon, nitrogen, and hydrogen, resembles a plastic polymer.

Implications for Our Understanding of Ice Giants

Militzer’s findings have significant implications for our understanding of the internal structures of Uranus and Neptune. His research provides a coherent explanation for the observed magnetic fields, which has been a long-standing puzzle in planetary science. The discovery also opens up new avenues for exploring the properties of materials under extreme conditions.

Future Research Directions

To further validate these findings, Militzer plans to collaborate with colleagues who can conduct laboratory experiments under extremely high temperatures and pressures. A proposed NASA mission to Uranus could also provide confirmation by measuring the planet’s vibrations using a Doppler imager. Additionally, Militzer aims to use his computational model to calculate how the planetary vibrations would differ between a layered and convective planet.

This breakthrough research, supported by the National Science Foundation, has far-reaching implications for our understanding of the ice giants in our solar system. As we continue to explore the mysteries of Uranus and Neptune, we may uncover even more surprises that challenge our current understanding of planetary formation and evolution.

External Link: Click Here For More