A team led by researchers from the University of Tokyo and IBM Quantum has achieved a significant milestone in quantum computing, demonstrating ground state energy calculations on systems up to 56 qubits using the Krylov quantum diagonalization (KQD) algorithm. Published in Nature Communications, this work by Nobuyuki Yoshioka, Mirko Amico, William Kirby and colleagues represents a crucial advance in quantum many-body simulation, bridging the gap between small-scale variational demonstrations and the promise of fault-tolerant quantum computing.

The fundamental challenge of solving the Schrödinger equation for quantum many-body systems lies at the heart of computational physics, chemistry, and materials science. While variational quantum eigensolvers (VQE) have dominated near-term quantum computing experiments, their lack of convergence guarantees and impractical optimization requirements have prevented systematic scaling. This new work demonstrates that KQD offers a compelling alternative, combining the near-term feasibility of variational methods with the theoretical guarantees typically associated with quantum phase estimation.

The Krylov Quantum Diagonalization Approach

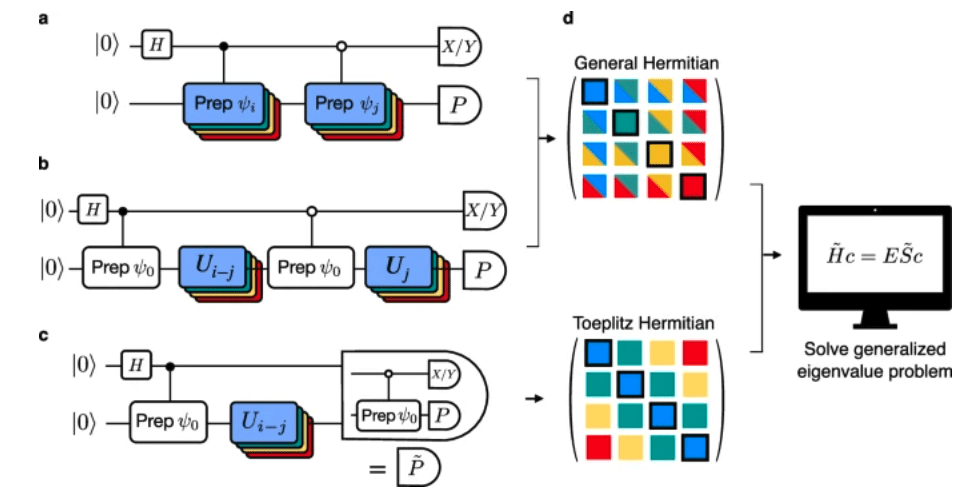

The KQD algorithm represents a quantum adaptation of classical Krylov subspace methods, which have long been workhorses of computational linear algebra. The key insight is to use a quantum processor to construct a subspace of the full Hilbert space through time evolution, then classically diagonalize the Hamiltonian within this reduced space. This hybrid approach cleverly sidesteps both the exponential memory requirements that plague classical methods and the deep circuits that make full quantum algorithms impractical on current hardware.

The method constructs a Krylov subspace by applying powers of the time evolution operator to an initial reference state. Specifically, the subspace is spanned by states of the form U^j|ψ₀⟩, where U = e^(-iHdt) is the time evolution operator and j ranges from 0 to D-1, with D being the subspace dimension. The quantum processor evaluates matrix elements of the Hamiltonian and overlap matrix within this subspace, which are then used to solve a generalized eigenvalue problem classically.

What makes this approach particularly suitable for near-term quantum devices is that time evolution can be approximated using relatively shallow circuits through Trotterization. The researchers implemented second-order Trotter decompositions, balancing accuracy against circuit depth constraints. Moreover, the method exhibits exponential convergence toward the ground state energy with increasing subspace dimension, a property that persists even in the presence of moderate noise levels.

Experimental Implementation on IBM Hardware

The experiments were conducted on IBM’s Heron processor, specifically the IBM_montecarlo system. This 133-qubit device features fixed-frequency transmon qubits connected via tunable couplers, offering faster two-qubit gates and reduced crosstalk compared to earlier generations. The heavy-hexagonal connectivity of the processor proved particularly well-suited to the problem structure, allowing efficient implementation of the required quantum circuits.

The research team studied the antiferromagnetic Heisenberg model on heavy-hexagonal lattices, a fundamental model in condensed matter physics. By exploiting the U(1) symmetry of the model, which corresponds to conservation of particle number in the computational basis, they could significantly simplify the quantum circuits. This symmetry-based approach eliminated the need for controlled time evolutions in the standard Hadamard test, reducing circuit depth and improving feasibility on noisy hardware.

Three different particle-number sectors were investigated, with k = 1, 3, and 5 particles. The single-particle experiment utilized 57 qubits, while the 3-particle and 5-particle experiments employed 45 and 43 qubits respectively. The 5-particle subspace had a dimension of 850,668, exceeding the full Hilbert space dimension of 19 qubits and approaching that of 20 qubits, demonstrating the method’s ability to access large effective Hilbert spaces even when restricted to symmetry sectors.

Advanced Error Mitigation Strategies

Given the challenges of operating in the NISQ era, the success of these large-scale experiments relied heavily on sophisticated error mitigation techniques. The team employed probabilistic error amplification (PEA) to extrapolate to the zero-noise limit, combined with twirled readout error extinction (TREX) to mitigate state preparation and measurement errors.

Pauli twirling was used to tailor the noise to a sparse Pauli-Lindblad model, simplifying the error characterization and mitigation process. The heavy-hexagonal lattice structure enabled implementation using only three distinct two-qubit gate layers, corresponding to a three-coloring of the lattice edges. This minimized the number of noise models that needed to be learned for PEA, improving the scalability of the error mitigation procedure.

The experimental protocol involved generating multiple twirled instances for each measurement basis, with different noise amplification factors applied. For the single-particle experiments, 300 twirled instances with 500 shots each were used at amplification factors of 1, 1.5, and 3. The multi-particle experiments used 100 twirled instances to manage total runtime, with adjusted amplification factors to account for increased circuit depths.

Convergence Analysis and Results

The experimental results demonstrated the expected exponential convergence of the ground state energy with increasing Krylov dimension, validating the theoretical predictions for KQD in the presence of noise. The convergence curves serve as diagnostic tools, distinguishing between coherent quantum evolution and noise-dominated behavior. The observed rapid initial convergence confirms that the quantum signal was successfully resolved despite the presence of hardware noise.

For the 3-particle and 5-particle sectors, the experimental energies were consistent with ideal classical simulations within error bars at nearly all points. The single-particle experiment showed some deviation below the true ground state energy, suggesting effective leakage out of the symmetry sector due to noise. This highlights both the power and limitations of symmetry-restricted calculations on noisy hardware.

The team fixed the Krylov dimension at D = 10 across all experiments to ensure completion within the device recalibration window of 24 hours. Time steps were chosen heuristically based on the restricted particle-number subspaces, with values of 0.5, 0.022, and 0.1 for k = 1, 3, and 5 respectively. These choices balanced the theoretical optimal value against practical considerations of the symmetry-restricted dynamics.

Comparison with Alternative Approaches

The paper positions KQD as filling a crucial gap in the quantum algorithm landscape for ground state problems. Unlike VQE, which requires iterative classical optimization with no convergence guarantees, KQD achieves variational results through a single round of quantum circuit executions followed by classical post-processing. Compared to quantum phase estimation, KQD requires significantly shallower circuits, making it practical for near-term devices while still maintaining theoretical accuracy bounds.

The authors note that other recently developed algorithms for ground state estimation extract eigenenergies from time evolution rather than direct Hamiltonian projection. This becomes problematic when Trotter circuits are held fixed to minimize depth, as the Trotter spectrum diverges from the ideal evolution spectrum. KQD’s direct projection approach avoids this issue, maintaining convergence even with fixed Trotter decompositions.

A complementary approach called sample-based quantum diagonalization (SQD), recently used in quantum-classical hybrid computing demonstrations, offers classically verifiable energies without time evolution approximation. However, KQD’s provable convergence guarantees and feasibility for condensed matter applications make it particularly suitable for the problems studied in this work.

Implications for Quantum Computing Development

This demonstration represents more than a factor of two increase in qubit count and over two orders of magnitude increase in effective Hilbert space dimension compared to previous end-to-end quantum algorithm demonstrations for ground state problems. The success on 56-qubit systems with Hilbert space dimensions approaching 10^6 marks a significant milestone in practical quantum advantage for many-body physics.

The work provides valuable insights for the development of quantum algorithms in the pre-fault-tolerant era. By showing that meaningful convergence can be achieved despite hardware noise, it validates the strategy of developing algorithms with built-in noise resilience rather than waiting for fully error-corrected quantum computers. The exponential convergence property of KQD, maintained even in noisy conditions, suggests that useful quantum simulations may be achievable with modest improvements in hardware quality.

The heavy-hexagonal architecture of the IBM Quantum processors proved well-suited to the problem structure, highlighting the importance of co-designing algorithms and hardware architectures. The ability to implement all required operations using only three distinct two-qubit gate layers demonstrates how architectural constraints can be turned into advantages through clever algorithm design.

Future Directions and Challenges

While the results are impressive, significant challenges remain for achieving chemical accuracy in quantum simulations. The gap between experimental and exact energies, while showing correct convergence trends, indicates that further improvements in both hardware and error mitigation will be necessary for quantitative predictions. The restriction to symmetry sectors, while enabling larger effective system sizes, also introduces vulnerabilities to symmetry-breaking noise effects.

Future work might explore extending KQD to more complex Hamiltonians, including those relevant to quantum chemistry and materials science. The method’s reliance on time evolution suggests natural extensions to studying dynamical properties and excited states. Integration with quantum error correction as it becomes available could dramatically improve accuracy while maintaining the algorithm’s favorable scaling properties.

The development of automated protocols for choosing optimal time steps and Krylov dimensions based on problem structure and hardware characteristics could make the method more broadly accessible. Similarly, advances in quantum compilation specifically tailored to KQD’s circuit structure could further reduce resource requirements.

Conclusion – A New Tool in the Quantum Toolkit

The successful demonstration of Krylov quantum diagonalization on 56-qubit systems represents a significant advance in practical quantum computing for many-body physics. By combining the near-term feasibility of variational methods with the theoretical rigor of subspace diagonalization, KQD offers a promising path forward for quantum simulation in the NISQ era and beyond.

This work exemplifies the importance of algorithm-hardware co-design and sophisticated error mitigation in pushing the boundaries of current quantum processors. As quantum hardware continues to improve and error correction capabilities develop, methods like KQD that exhibit favorable scaling with both system size and noise levels will likely play crucial roles in achieving practical quantum advantage for scientifically relevant problems. The demonstration that meaningful quantum simulations can be performed on systems approaching 60 qubits with effective Hilbert spaces of nearly a million dimensions marks a pivotal moment in the journey toward useful quantum computing.