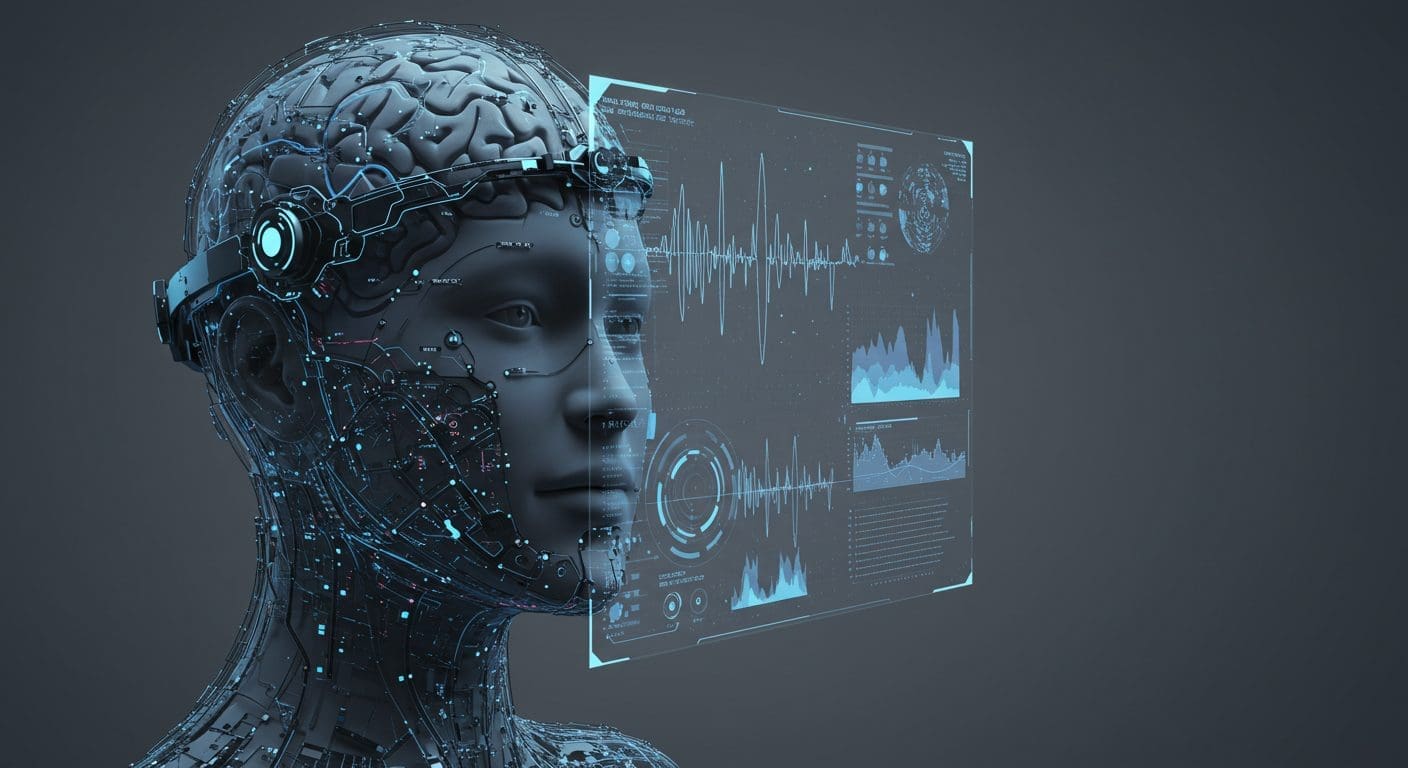

A brain-computer interface (BCI) is a system that allows people to control devices. It also lets them communicate with others using only their brain signals. BCIs have the potential to revolutionize the treatment of neurological disorders, such as paralysis, ALS, and stroke, by restoring sensory function in individuals with sensory impairments.

BCIs detect brain activity associated with specific thoughts or intentions and use that information to control a device or communicate a message. There are different types of BCIs, including invasive, partially invasive, and non-invasive systems, each with its own advantages and limitations. Researchers are exploring new techniques for decoding neural activity, such as functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) and machine learning algorithms.

Despite advances in BCI research, significant challenges remain to make BCIs more accessible and user-friendly. Current BCI systems often require extensive technical expertise to set up and operate, limiting their adoption in clinical settings. The high cost of BCI equipment is also a barrier to access. Researchers are working to develop more intuitive interfaces that can provide feedback to users, such as virtual reality (VR) or augmented reality (AR) environments.

- Definition Of Brain-Computer Interface

- History And Evolution Of BCI Technology

- Types Of Brain Computer Interfaces

- Invasive Vs Non-invasive Bcis

- Electroencephalography In BCI Systems

- Functional Near-infrared Spectroscopy

- Electrocorticography And Its Applications

- Neural Implants For BCI Systems

- Brain Signal Processing And Analysis

- BCI Applications In Medicine And Healthcare

- Neuroprosthetics And Assistive Technology

- Future Directions And Challenges In BCI Research

Definition Of Brain-Computer Interface

A Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) is a system that enables people to control devices or communicate with others using only their brain signals. This technology relies on the detection and analysis of neural activity, which can be achieved through various methods such as electroencephalography (EEG), magnetoencephalography (MEG), functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS), or invasive recordings using electrodes implanted directly into the brain.

The primary goal of a BCI is to provide individuals with severe motor disabilities, such as paralysis or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), with an alternative means of communication and control. BCIs can also be used for neuroprosthetic applications, where they enable people to control prosthetic limbs or other devices using their brain signals. In addition, BCIs have the potential to enhance human cognition and performance in various fields such as gaming, education, and healthcare.

BCIs typically consist of several components: a signal acquisition module that records neural activity, a signal processing module that extracts relevant features from the recorded data, and a device control module that translates the extracted features into commands for controlling external devices. The development of BCIs requires an interdisciplinary approach, involving expertise in neuroscience, computer science, engineering, and mathematics.

One of the key challenges in BCI research is the development of robust and accurate algorithms for decoding neural activity. This involves identifying patterns in brain signals that correspond to specific thoughts, intentions, or actions. Recent advances in machine learning and deep learning have significantly improved the performance of BCIs, enabling them to achieve high levels of accuracy and speed.

BCIs can be categorized into two main types: invasive and non-invasive. Invasive BCIs involve implanting electrodes directly into the brain, which provides high spatial resolution but carries risks such as tissue damage and infection. Non-invasive BCIs use external sensors to record neural activity, which is safer but may have lower spatial resolution.

The development of BCIs has significant implications for various fields, including healthcare, education, and entertainment. For instance, BCIs can enable people with severe motor disabilities to interact with their environment in ways that were previously impossible. Additionally, BCIs can be used to develop new forms of human-computer interaction, such as brain-controlled gaming or virtual reality experiences.

History And Evolution Of BCI Technology

The concept of Brain Computer Interfaces (BCIs) dates back to the 1960s, when computer scientist Alan Newell and neuroscientist Theodore Bullock began exploring ways to decode brain signals into machine commands. One of the earliest recorded experiments in BCI technology was conducted by Dr. Eberhard Fetz in 1969, where he demonstrated that monkeys could control a robotic arm using neural activity from their motor cortex.

In the 1970s and 1980s, BCIs began to gain more attention, with researchers like Dr. Jacques Vidal exploring the use of electroencephalography (EEG) to decode brain signals. Vidal’s work laid the foundation for modern BCI systems that rely on EEG or other non-invasive methods to read brain activity. During this period, BCIs were primarily used in research settings to study neural function and behavior.

The 1990s saw significant advancements in BCI technology, with the development of more sophisticated algorithms and signal processing techniques. Researchers like Dr. Jonathan Wolpaw began exploring the use of BCIs for assistive technologies, such as communication devices for individuals with paralysis or ALS. This work led to the creation of the first commercial BCI systems, which were primarily used in research settings.

In the 2000s, BCIs started to gain more mainstream attention, with the development of non-invasive BCI systems that could be used by anyone. Companies like NeuroSky and Emotiv began marketing consumer-grade BCI headsets that allowed users to control games or other applications using their brain activity. This period also saw significant advancements in the use of BCIs for neurological disorders, such as epilepsy and Parkinson’s disease.

Recent years have seen a surge in interest in BCIs, with major tech companies like Facebook and Neuralink investing heavily in BCI research and development. Modern BCI systems are becoming increasingly sophisticated, with the ability to decode complex brain signals and control a wide range of devices. Researchers are also exploring new applications for BCIs, such as neuroprosthetics and neural implants.

The field of BCI technology is rapidly evolving, with new breakthroughs and advancements being reported regularly. As researchers continue to push the boundaries of what is possible with BCIs, we can expect to see significant improvements in the lives of individuals with neurological disorders, as well as new applications for BCIs in fields like gaming and education.

Types Of Brain Computer Interfaces

Invasive Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs) involve the implantation of electrodes directly into the brain to record neural activity. This type of BCI is typically used in individuals with severe motor disorders, such as paralysis or ALS, and can provide a high degree of control over devices. For example, studies have shown that individuals with invasive BCIs can achieve high accuracy rates when controlling computer cursors . However, the risks associated with surgery and the potential for tissue damage limit the widespread adoption of this technology.

Partially Invasive Brain-Computer Interfaces involve the placement of electrodes into the skull, but not directly into the brain. This type of BCI is less invasive than fully invasive BCIs and can still provide a high degree of control over devices. For example, studies have shown that partially invasive BCIs can be used to control prosthetic limbs . However, the signal quality may be lower compared to fully invasive BCIs.

Non-Invasive Brain-Computer Interfaces use external sensors to record neural activity from the scalp or other parts of the body. This type of BCI is less accurate than invasive and partially invasive BCIs but has the advantage of being non-invasive and relatively low-cost. For example, studies have shown that non-invasive BCIs can be used to control computer games . However, the signal quality may be lower compared to invasive and partially invasive BCIs.

Electrocorticography (ECoG) is a type of BCI that involves the placement of electrodes directly on the surface of the brain. This type of BCI provides high spatial resolution and can be used to control devices with high accuracy. For example, studies have shown that ECoG can be used to control robotic arms .

Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS) is a non-invasive BCI technique that uses light to measure changes in blood oxygenation levels in the brain. This type of BCI provides low spatial resolution but has the advantage of being portable and relatively low-cost. For example, studies have shown that fNIRS can be used to control computer cursors .

Brain-Computer Interfaces based on electroencephalography (EEG) use external electrodes to record neural activity from the scalp. This type of BCI provides low spatial resolution but has the advantage of being non-invasive and relatively low-cost. For example, studies have shown that EEG-based BCIs can be used to control computer games .

Invasive Vs Non-invasive Bcis

Invasive Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCIs) involve the implantation of electrodes directly into the brain to record neural activity. This approach allows for high spatial resolution and signal-to-noise ratio, enabling precise control over devices such as prosthetic limbs or computers. However, invasive BCIs carry risks associated with surgery, including infection, tissue damage, and scarring (Leuthardt et al., 2006; Moritz et al., 2008).

Non-invasive BCIs, on the other hand, use external sensors to detect neural activity through techniques such as electroencephalography (EEG), functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS), or magnetoencephalography (MEG). These methods are less accurate and have lower spatial resolution compared to invasive BCIs but offer a safer and more convenient alternative. Non-invasive BCIs can be used for applications such as gaming, communication, and control of devices, but their performance is often limited by signal quality and noise (Wolpaw et al., 2002; Blankertz et al., 2010).

The choice between invasive and non-invasive BCIs depends on the specific application and user needs. Invasive BCIs are typically reserved for individuals with severe motor disorders, such as paralysis or ALS, who require precise control over devices to interact with their environment (Hochberg et al., 2006). Non-invasive BCIs, in contrast, are more suitable for users who require less precise control, such as gamers or individuals with mild motor impairments.

Recent advances in non-invasive BCI technology have led to the development of dry EEG electrodes and other innovative sensors that improve signal quality and user comfort (Liao et al., 2012; Mullen et al., 2015). These advancements have expanded the potential applications of non-invasive BCIs, making them more viable for a broader range of users.

In contrast, invasive BCI technology has also seen significant progress, with the development of implantable neural interfaces that can record and stimulate neural activity with high precision (Nicolelis et al., 2003; Leuthardt et al., 2006). These advancements have improved the performance and safety of invasive BCIs, making them more suitable for individuals who require precise control over devices.

The development of hybrid BCIs that combine elements of both invasive and non-invasive approaches is an active area of research (Wolpaw et al., 2012; Müller-Putz et al., 2015). These systems aim to leverage the strengths of each approach, offering improved performance, safety, and user convenience.

Electroencephalography In BCI Systems

Electroencephalography (EEG) is a crucial component in Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) systems, enabling the detection of neural activity associated with specific cognitive processes. EEG measures the electrical activity of the brain through electrodes placed on the scalp, providing a non-invasive and relatively low-cost method for acquiring neural signals. The spatial resolution of EEG is limited compared to other neuroimaging techniques, such as functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), but its high temporal resolution makes it suitable for detecting rapid changes in neural activity.

In BCI systems, EEG signals are typically filtered and processed using various algorithms to extract features that can be used for classification or control. The most common frequency bands of interest in EEG-based BCIs include alpha (8-12 Hz), beta (13-30 Hz), and theta (4-7 Hz) waves, which are associated with different cognitive states, such as relaxation, attention, and memory recall. For example, the alpha band is often used for detecting changes in attention or relaxation levels, while the beta band is commonly used for detecting motor imagery.

The use of EEG in BCIs has been extensively explored in various applications, including communication systems for individuals with severe paralysis or ALS, control of prosthetic limbs, and gaming. In these applications, EEG signals are often classified using machine learning algorithms, such as support vector machines (SVMs) or neural networks, to detect specific patterns or features that correspond to different commands or actions.

One of the key challenges in EEG-based BCIs is the low signal-to-noise ratio (SNR), which can result from various sources of noise, including muscle activity, eye movements, and electrical interference. To address this challenge, researchers have developed various techniques for noise reduction and artifact removal, such as independent component analysis (ICA) and wavelet denoising.

Recent advances in EEG-based BCIs include the development of dry electrodes that do not require gel or paste to establish contact with the scalp, reducing setup time and increasing user comfort. Additionally, the use of mobile EEG devices has enabled the deployment of BCIs in real-world settings, such as homes and public spaces, expanding their potential for practical applications.

The integration of EEG with other modalities, such as functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) or electrocorticography (ECoG), has also been explored to improve the spatial resolution and accuracy of BCIs. These multimodal approaches can provide a more comprehensive understanding of neural activity and its relationship to cognitive processes.

Functional Near-infrared Spectroscopy

Functional Near-Infrared Spectroscopy (fNIRS) is a non-invasive neuroimaging technique that utilizes near-infrared light to measure changes in cerebral blood oxygenation and volume. This method is based on the principle that near-infrared light can penetrate the scalp and skull, allowing for the detection of changes in brain activity. fNIRS measures the absorption of near-infrared light by oxyhemoglobin (oxy-Hb) and deoxyhemoglobin (deoxy-Hb), which are indicators of neural activity.

The spatial resolution of fNIRS is typically limited to several centimeters, but its temporal resolution can be as high as 100 Hz. This makes it suitable for measuring changes in brain activity over short periods, such as during cognitive tasks or motor activities. fNIRS has been used to study a wide range of cognitive functions, including attention, memory, and language processing.

fNIRS is often compared to functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), which measures changes in blood oxygenation using magnetic fields. While fMRI provides higher spatial resolution than fNIRS, it requires subjects to remain still within the scanner, limiting its use for certain populations or tasks. In contrast, fNIRS can be used with subjects who are moving or performing tasks outside of a scanner.

The development of portable and wearable fNIRS devices has expanded its potential applications, including brain-computer interfaces (BCIs), neurofeedback training, and sports performance monitoring. These devices typically consist of a sensor that emits near-infrared light and detects the reflected signal, which is then processed to extract information about brain activity.

fNIRS has also been used in combination with other techniques, such as electroencephalography (EEG) or magnetoencephalography (MEG), to provide complementary information about brain activity. This multimodal approach can help to improve the spatial and temporal resolution of fNIRS measurements, allowing for a more comprehensive understanding of brain function.

The use of fNIRS in BCIs has shown promise for applications such as controlling prosthetic devices or communicating through text or speech synthesis. However, further research is needed to develop more sophisticated algorithms for decoding brain activity from fNIRS signals and to improve the accuracy and reliability of these systems.

Electrocorticography And Its Applications

Electrocorticography (ECoG) is a neuroimaging technique that records the electrical activity of the brain through electrodes placed directly on the surface of the cortex. This method provides high spatial and temporal resolution, allowing researchers to study the neural activity underlying various cognitive processes. ECoG signals are typically in the range of 1-100 Hz and can be used to decode motor intentions, such as hand movements or finger gestures.

ECoG has been widely used in brain-computer interface (BCI) applications, where it serves as a control signal for devices such as prosthetic limbs or computer cursors. For instance, studies have shown that ECoG signals from the motor cortex can be used to control a robotic arm with high accuracy. Additionally, ECoG has been employed in neuroprosthetic devices, which aim to restore motor function in individuals with paralysis or other motor disorders.

The spatial resolution of ECoG is higher than that of electroencephalography (EEG), another non-invasive neuroimaging technique. This is because ECoG electrodes are placed directly on the brain surface, allowing for more precise recordings of neural activity. However, ECoG requires surgical implantation of electrodes, which can be invasive and carries risks such as infection or tissue damage.

ECoG has also been used in various clinical applications, including epilepsy diagnosis and treatment. For example, studies have shown that ECoG can be used to identify the seizure onset zone in individuals with epilepsy, allowing for more targeted therapeutic interventions. Furthermore, ECoG has been employed in neurofeedback training, where it provides individuals with real-time feedback on their brain activity.

Recent advances in ECoG technology have led to the development of high-density electrode arrays, which can record neural activity from hundreds of channels simultaneously. This has enabled researchers to study complex cognitive processes such as attention and memory with unprecedented spatial and temporal resolution.

The use of ECoG in BCI applications has also been extended to non-motor functions, such as language processing and decision-making. For instance, studies have shown that ECoG signals from the prefrontal cortex can be used to decode linguistic information, allowing individuals to communicate through a computer interface.

Neural Implants For BCI Systems

Neural implants for Brain-Computer Interface (BCI) systems are designed to read and write neural signals directly from the brain, enabling people to control devices with their thoughts. These implants typically consist of an array of electrodes that are surgically implanted in specific areas of the brain, such as the motor cortex or sensory cortex. The electrodes detect electrical activity in the brain, which is then decoded by algorithms to determine the user’s intentions.

The development of neural implants for BCI systems has been driven by advances in fields such as neuroscience, computer science, and engineering. For example, researchers have made significant progress in understanding the neural code, which refers to the way in which the brain represents information. This knowledge has enabled the development of more sophisticated algorithms for decoding neural activity.

One type of neural implant that has shown promise for BCI applications is the Utah array, a 100-electrode array developed by researchers at the University of Utah. The Utah array has been used in several studies to demonstrate the feasibility of using neural implants for BCI control. For example, one study published in the journal Nature demonstrated that a paralyzed individual was able to control a computer cursor with their thoughts using a Utah array implant.

Another type of neural implant that is being developed for BCI applications is the Neuralink implant, which consists of a thin, flexible probe with 1,024 electrodes. The Neuralink implant is designed to be implanted in the brain through a minimally invasive procedure and has been demonstrated to be capable of reading and writing neural signals at high speeds.

The use of neural implants for BCI systems raises several technical challenges, including the need for high-bandwidth data transmission and the development of sophisticated algorithms for decoding neural activity. Additionally, there are also concerns about the safety and efficacy of these devices, as well as their potential impact on society.

Researchers have made significant progress in addressing these challenges, however. For example, one study published in the journal Science demonstrated that a high-bandwidth BCI system using a neural implant was able to achieve high levels of accuracy and speed in controlling a computer cursor.

Brain Signal Processing And Analysis

Brain Signal Processing and Analysis is a crucial component of Brain Computer Interfaces (BCIs). The process involves the acquisition, processing, and interpretation of brain signals to extract meaningful information. This is typically achieved through the use of electroencephalography (EEG), which measures the electrical activity of the brain through electrodes placed on the scalp. EEG signals are then filtered and processed using various techniques, such as time-frequency analysis and independent component analysis, to remove noise and artifacts.

The goal of brain signal processing and analysis is to identify specific patterns or features in the brain activity that can be used to control a device or communicate information. This requires the development of sophisticated algorithms and machine learning models that can accurately classify and decode the brain signals. For example, studies have shown that EEG-based BCIs can achieve high accuracy in decoding motor imagery tasks, such as hand movement and finger tapping.

One of the key challenges in brain signal processing and analysis is dealing with the inherent variability and noise in the brain activity. This can be addressed through the use of advanced signal processing techniques, such as wavelet denoising and sparse representation, which can help to remove noise and artifacts from the EEG signals. Additionally, the use of machine learning models, such as deep neural networks, can help to improve the accuracy and robustness of brain signal classification.

Another important aspect of brain signal processing and analysis is the development of real-time systems that can process and analyze brain activity in real-time. This requires the use of high-performance computing hardware and software, such as graphics processing units (GPUs) and field-programmable gate arrays (FPGAs), which can provide fast and efficient processing of large amounts of data.

The analysis of brain signals also involves the identification of specific frequency bands that are associated with different cognitive processes. For example, studies have shown that the alpha band (8-12 Hz) is associated with relaxation and closed eyes, while the beta band (13-30 Hz) is associated with attention and motor activity. The use of these frequency bands can help to improve the accuracy and robustness of brain signal classification.

The development of brain signal processing and analysis algorithms also involves the use of various metrics and evaluation criteria, such as accuracy, precision, and recall, which are used to assess the performance of the system. These metrics provide a quantitative measure of how well the system is performing and can help to identify areas for improvement.

BCI Applications In Medicine And Healthcare

Brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) have been increasingly used to help individuals with neurological disorders, such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), Parkinson’s disease, and stroke. BCIs can provide a means of communication and control for people who are unable to speak or move due to their condition. For example, studies have shown that ALS patients can use BCIs to communicate through typing or speaking synthesized text . Additionally, BCIs have been used to help individuals with Parkinson’s disease control their movements and reduce tremors .

BCIs are also being used to improve the control of prosthetic limbs. By using electroencephalography (EEG) or other techniques to read brain signals, individuals can control their prosthetic limbs with greater precision and accuracy. For example, studies have shown that individuals with amputations can use BCIs to control their prosthetic arms and perform tasks such as grasping and manipulating objects . Additionally, BCIs are being used to improve the fit and function of orthotics, such as exoskeletons, which can help individuals with paralysis or muscle weakness walk again .

BCIs are also being used to restore sensory function in individuals who have lost their senses due to injury or disease. For example, studies have shown that BCIs can be used to restore vision in individuals who are blind by bypassing damaged or non-functioning photoreceptors and directly stimulating the retina . Additionally, BCIs are being used to restore hearing in individuals who are deaf or hard of hearing by directly stimulating the auditory nerve .

BCIs are also being used to promote neuroplasticity and recovery in individuals with neurological disorders. By using BCIs to provide feedback and reinforcement, individuals can relearn lost skills and functions. For example, studies have shown that BCIs can be used to improve cognitive function in individuals with stroke or traumatic brain injury . Additionally, BCIs are being used to promote motor recovery in individuals with spinal cord injuries .

Several clinical trials are currently underway to test the safety and efficacy of BCIs in various medical applications. For example, a clinical trial is currently testing the use of BCIs to restore vision in individuals who are blind due to retinitis pigmentosa . Additionally, a clinical trial is currently testing the use of BCIs to improve motor function in individuals with ALS .

Neuroprosthetics And Assistive Technology

Neuroprosthetics is a subfield of neuroscience that focuses on developing artificial devices to replace or restore damaged or missing neural tissue, with the ultimate goal of improving cognitive and motor function in individuals with neurological disorders (Katz et al., 2012; Nicolelis, 2003). One of the key applications of neuroprosthetics is in the development of brain-computer interfaces (BCIs), which enable people to control devices or communicate using only their thoughts. BCIs typically involve the use of electroencephalography (EEG) or other techniques to record neural activity, which is then translated into a digital signal that can be used to control a device.

Invasive BCIs, which involve implanting electrodes directly into the brain, have been shown to provide high spatial resolution and fast communication rates, but are typically reserved for individuals with severe paralysis or other motor disorders (Leuthardt et al., 2006; Serruya et al., 2002). Non-invasive BCIs, on the other hand, use external electrodes to record neural activity and are more suitable for individuals with less severe impairments. However, non-invasive BCIs typically have lower spatial resolution and slower communication rates compared to invasive BCIs.

Assistive technology, such as prosthetic limbs and exoskeletons, can be controlled using BCIs, allowing individuals with motor disorders to regain some level of independence (Kuiken et al., 2009; Farry et al., 2010). For example, a study published in the journal Science Translational Medicine demonstrated that a paralyzed individual was able to control a robotic arm using an invasive BCI, allowing them to perform tasks such as feeding themselves and brushing their teeth (Leuthardt et al., 2006).

Neuroprosthetic devices can also be used to restore sensory function in individuals with sensory impairments. For example, cochlear implants have been developed to restore hearing in individuals with severe hearing loss (Zeng et al., 2012). Similarly, retinal implants have been developed to restore vision in individuals with certain types of blindness (Humayun et al., 2012).

The development of neuroprosthetic devices is a rapidly advancing field, with new technologies and techniques being developed continuously. However, there are still many challenges that must be overcome before these devices can be widely adopted, including improving their safety, efficacy, and usability.

Neuroprosthetic devices have the potential to revolutionize the treatment of neurological disorders, but more research is needed to fully realize their potential. Further studies are needed to improve our understanding of how these devices interact with the brain and to develop new technologies that can be used to restore cognitive and motor function in individuals with neurological disorders.

Future Directions And Challenges In BCI Research

Advances in brain-computer interface (BCI) research have led to the development of various applications, including those for individuals with paralysis or ALS. However, there are still significant challenges that need to be addressed to improve the accuracy and reliability of BCIs. One major challenge is the limited understanding of the neural code, which hinders the development of more sophisticated BCI systems (Koch et al., 2006; Nicolelis, 2003). Furthermore, current BCI systems often rely on invasive methods, such as electrocorticography or intracortical recordings, which can be risky and have limited spatial resolution.

To overcome these challenges, researchers are exploring new techniques for decoding neural activity. For example, studies have shown that functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) can be used to decode brain activity with high accuracy (Cui et al., 2010; Sitaram et al., 2007). Additionally, advances in machine learning algorithms have enabled the development of more sophisticated BCI systems that can learn from user feedback and adapt to changing neural patterns (Lotte et al., 2018; Müller-Putz et al., 2015).

Another area of research is focused on developing BCIs that individuals with severe motor disorders can use. For example, studies have shown that BCIs based on electroencephalography (EEG) or electromyography (EMG) can be used to control prosthetic limbs or communicate through text messages (Kübler et al., 2005; Müller-Putz et al., 2010). However, these systems often require extensive training and have limited accuracy.

To improve the usability of BCIs, researchers are also exploring new interfaces that can provide more intuitive feedback to users. For example, studies have shown that virtual reality (VR) or augmented reality (AR) environments can be used to enhance user engagement and improve BCI performance (Lécuyer et al., 2008; Pfurtscheller et al., 2010).

Despite these advances, significant challenges still need to be addressed to make BCIs more accessible and user-friendly. For example, current BCI systems often require extensive technical expertise to set up and operate, which can limit their adoption in clinical settings (Kübler et al., 2005). Furthermore, the high cost of BCI equipment can also restrict access to these technologies.