The universe, in its vastness and complexity, has long captivated physicists and mathematicians alike. While quantum mechanics and general relativity offer powerful descriptions of its behavior, a nagging question remains: is there a simpler, more fundamental level at which reality operates?

The Echo of Game of Life: Conway’s Universe and the Fabric of Reality

The universe, in its vastness and complexity, has long captivated physicists and mathematicians alike. While quantum mechanics and general relativity offer powerful descriptions of its behavior, a nagging question remains: is there a simpler, more fundamental level at which reality operates? John Conway, a British mathematician renowned for his playful yet profound mathematical creations, proposed a startling answer. His Game of Life, a zero-player cellular automaton, isn’t just a fascinating computer simulation; Conway suggested it could be a model for the universe itself. This idea, initially dismissed as philosophical musing, is now receiving renewed attention as physicists explore the limits of our current understanding and search for a deeper, more elegant framework for describing existence. Conway’s vision, though radical, challenges us to consider that the universe might not be governed by continuous laws, but by discrete, rule-based processes, much like the simple patterns unfolding on a digital grid.

The Hamiltonian That Launched a Field: Conway’s Rules and the Seeds of Simulation

John Conway, a professor at Princeton University known for his eccentric style and love of recreational mathematics, unveiled the Game of Life in 1970. It’s deceptively simple: a two-dimensional grid of cells, each either “alive” or “dead.” The fate of each cell in the next generation is determined by the number of its living neighbors, following three rules: a live cell with fewer than two live neighbors dies (underpopulation), a live cell with two or three live neighbors lives on, and a live cell with more than three live neighbors dies (overpopulation). Crucially, a dead cell with exactly three live neighbors becomes a live cell (reproduction). These rules, applied simultaneously to every cell, create emergent behavior, complex patterns, self-replicating structures, and even “gliders” that move across the grid. What makes the Game of Life so compelling isn’t the rules themselves, but the unexpected complexity that arises from their simple application. This ability to generate intricate behavior from minimal rules is precisely what drew Conway to believe it could be a metaphor for the universe.

From Gliders to Galaxies: The Emergence of Complexity

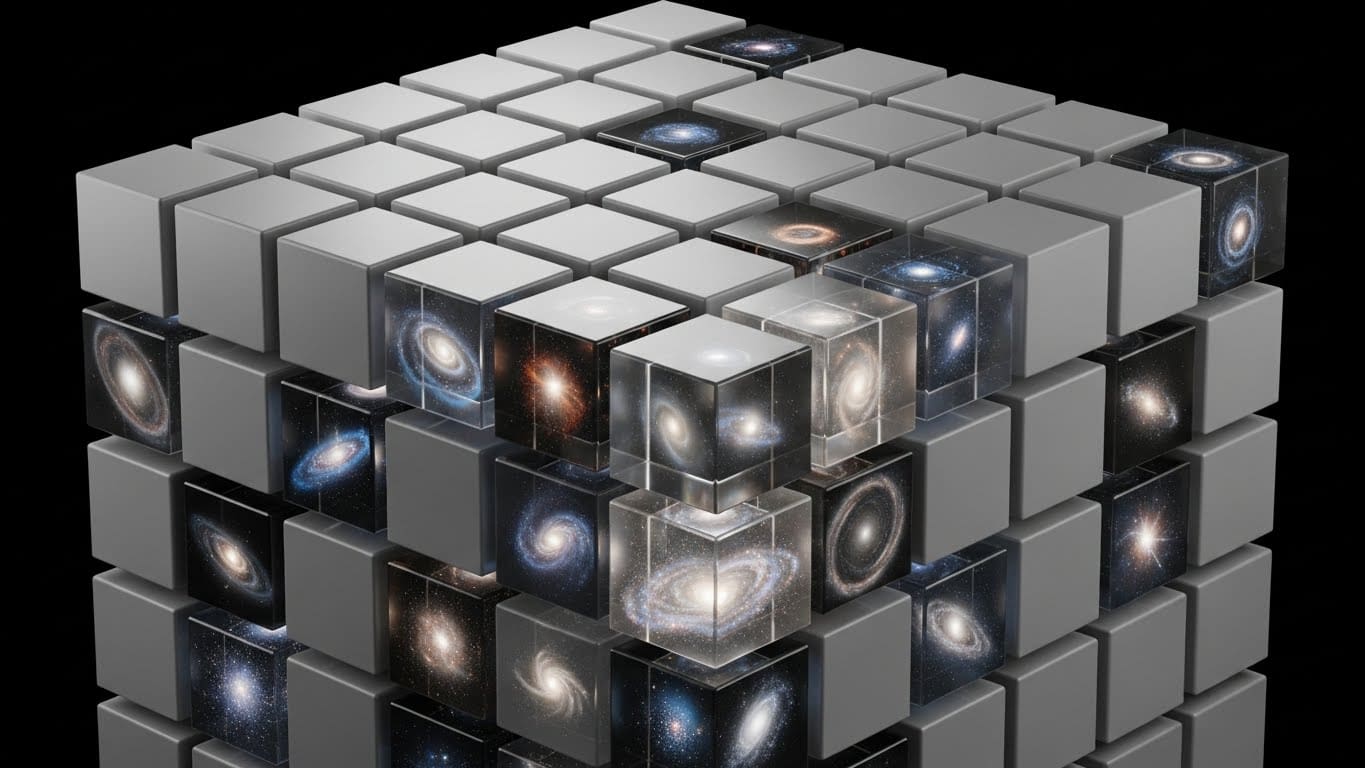

The power of the Game of Life lies in its ability to exhibit emergent behavior. Simple initial configurations can evolve into incredibly complex patterns, some of which are stable, others oscillating, and still others exhibiting seemingly random movement. These patterns aren’t programmed into the rules; they emerge from the interactions of the cells. This concept of emergence is central to Conway’s universe hypothesis. He proposed that the fundamental laws of physics, gravity, electromagnetism, quantum mechanics, might not be fundamental at all, but rather emergent properties of a deeper, underlying cellular automaton. Just as gliders and spaceships emerge from the simple rules of the Game of Life, so too might the particles and forces of nature emerge from the interactions of cells in a vast, cosmic automaton. This idea, while seemingly far-fetched, offers a potential solution to the long-standing problem of reconciling quantum mechanics and general relativity, two theories that describe the universe at different scales but remain stubbornly incompatible.

The Digital Physics Revolution: Cellular Automata and the Limits of Continuity

The idea of a digital universe, where reality is fundamentally discrete rather than continuous, isn’t new. Edward Fredkin, a computer scientist at MIT, was a pioneer of “digital physics” in the 1980s, arguing that the universe is ultimately a giant computer. Fredkin, along with Stephen Wolfram, explored the potential of cellular automata as models for physical reality. Wolfram, the creator of Mathematica and a leading proponent of computational irreducibility, argued that complex systems often cannot be simplified or predicted, even with complete knowledge of their initial conditions and rules. This aligns with Conway’s vision: if the universe is a cellular automaton, then its behavior is fundamentally unpredictable, except through direct simulation. The challenge, however, lies in finding the right rules, the equivalent of Conway’s Game of Life rules, that can reproduce the observed behavior of the universe.

Boltzmann Brains and the Problem of Initial Conditions

One significant hurdle for the cellular automaton universe hypothesis is the problem of initial conditions. If the universe began in a low-entropy state, as cosmology suggests, how did it arrive at such a specific and improbable configuration? The concept of Boltzmann brains, hypothetical self-aware entities that spontaneously arise from random fluctuations in a high-entropy universe, highlights this issue. If the universe is truly random at its base level, then Boltzmann brains should be far more common than actual observers like ourselves. This is a serious problem for any theory that relies on randomness as a fundamental principle. However, Conway’s Game of Life, with its deterministic rules, offers a potential solution. If the universe is governed by a set of fixed rules, then the initial conditions, while perhaps complex, are not necessarily random. They could be the result of a previous iteration of the automaton, or a more fundamental underlying structure.

The Holographic Principle and the Boundaries of Space-Time

The holographic principle, proposed by Gerard ‘t Hooft, the Dutch Nobel laureate, and Leonard Susskind, a Stanford physicist and pioneer of string theory, offers a fascinating connection to Conway’s ideas. The holographic principle suggests that all the information contained in a volume of space can be represented as encoded on its boundary. Imagine a 3D movie being projected from a flat 2D screen: the holographic principle proposes the universe works similarly. This principle, derived from black hole thermodynamics, implies that the universe might not be fundamentally three-dimensional, but rather a projection from a lower-dimensional surface. This resonates with the cellular automaton model, where the universe is essentially a two-dimensional grid of cells, and the three-dimensional world we perceive is an emergent property of their interactions. The boundary of the automaton, in this case, could be the surface from which the universe is projected.

Information as the Foundation: Deutsch’s ‘It From Bit’ and the Quantum Connection

John Wheeler, the Princeton physicist who coined the term ‘black hole’ and mentored Richard Feynman, proposed in 1990 that information is the foundation of physical reality. His phrase ‘it from bit’ captures the radical idea that every particle and force derives its existence from yes-or-no answers to quantum questions. This concept aligns perfectly with the cellular automaton model, where the universe is built from discrete units of information, the states of the cells. David Deutsch, the Oxford physicist who pioneered quantum computing theory, further developed this idea, arguing that quantum mechanics itself can be understood as a form of computation. If the universe is fundamentally computational, then the laws of physics are simply algorithms running on a cosmic computer.

Cooling Atoms to a Standstill: The Quest for Experimental Verification

While the cellular automaton universe hypothesis remains largely theoretical, there are ongoing efforts to explore its potential through experimentation. David Wineland, the NIST physicist who won the 2012 Nobel Prize for trapped ion work, and his colleagues are using trapped ions to simulate simple physical systems. Trapped ions, individual atoms held in place by electromagnetic fields, can be used as qubits, the basic units of quantum information. By manipulating these qubits, researchers can create and study artificial systems that mimic the behavior of the universe at a fundamental level. The goal is to determine whether these systems exhibit the same emergent properties as the real universe, and whether they can be described by the rules of a cellular automaton.

The Limits of Computation: Computational Irreducibility and the Unpredictable Universe

Stephen Wolfram, the creator of Mathematica, has championed the concept of computational irreducibility. This means that the only way to determine the future state of a complex system is to actually run the simulation, there are no shortcuts or analytical solutions. If the universe is computationally irreducible, then it is fundamentally unpredictable, even with complete knowledge of its initial conditions and laws. This has profound implications for our understanding of determinism and free will. If the universe is a cellular automaton, then its future is predetermined by its initial state and rules, but the complexity of the system makes it impossible for us to predict that future.

Beyond the Standard Model: Searching for Discrete Symmetries

The Standard Model of particle physics, while remarkably successful, leaves many questions unanswered. It doesn’t explain dark matter, dark energy, or the origin of mass. Some physicists believe that the answer lies in a deeper, more fundamental theory that incorporates discrete symmetries. These symmetries, unlike continuous symmetries, involve discrete transformations, such as rotations by specific angles. The rules of Conway’s Game of Life are inherently discrete, and it’s possible that the universe also operates according to discrete principles. Searching for these discrete symmetries in experimental data could provide evidence for the cellular automaton universe hypothesis.

The Price of Forgetting: Landauer’s Principle and the Thermodynamics of Information

The Landauer principle, established by IBM physicist Rolf Landauer in 1961, states that erasing one bit of information requires a minimum energy cost of kT ln(2) joules, where k is Boltzmann’s constant and T is temperature. At room temperature, this is about 0.000000000000000000003 joules per bit. This isn’t a practical engineering limit but a fundamental law of thermodynamics: forgetting has a physical price. This connection between information and energy is crucial to the cellular automaton model. If the universe is fundamentally computational, then the laws of physics must be consistent with the Landauer principle. The energy required to erase information in the universe could be the driving force behind the expansion of the universe and the arrow of time.

A Universe of Rules: The Enduring Legacy of Conway’s Vision

John Conway’s Game of Life, initially conceived as a mathematical curiosity, has evolved into a powerful metaphor for the universe itself. While the cellular automaton universe hypothesis remains speculative, it challenges us to rethink our fundamental assumptions about reality. It suggests that the universe might not be governed by continuous laws, but by discrete, rule-based processes. Conway’s playful yet profound vision reminds us that the simplest of rules can give rise to extraordinary complexity, and that the universe, in all its grandeur, might be more elegant and more predictable than we ever imagined. The echo of the Game of Life continues to resonate within the halls of theoretical physics, inspiring a new generation of scientists to explore the boundaries of our understanding and search for the ultimate rules that govern existence.