A breakthrough in quantum physics has emerged from a collaboration between researchers at the University of Regensburg and the University of Michigan. The team’s discovery could pave the way for advancements in quantum computing, sensing, and other technologies by harnessing the unique properties of chromium sulfide bromide, a material that supports nearly any method of physical information encoding: electric charge, photons (light), magnetism (electron spins), and phonons (vibrations, such as sound).

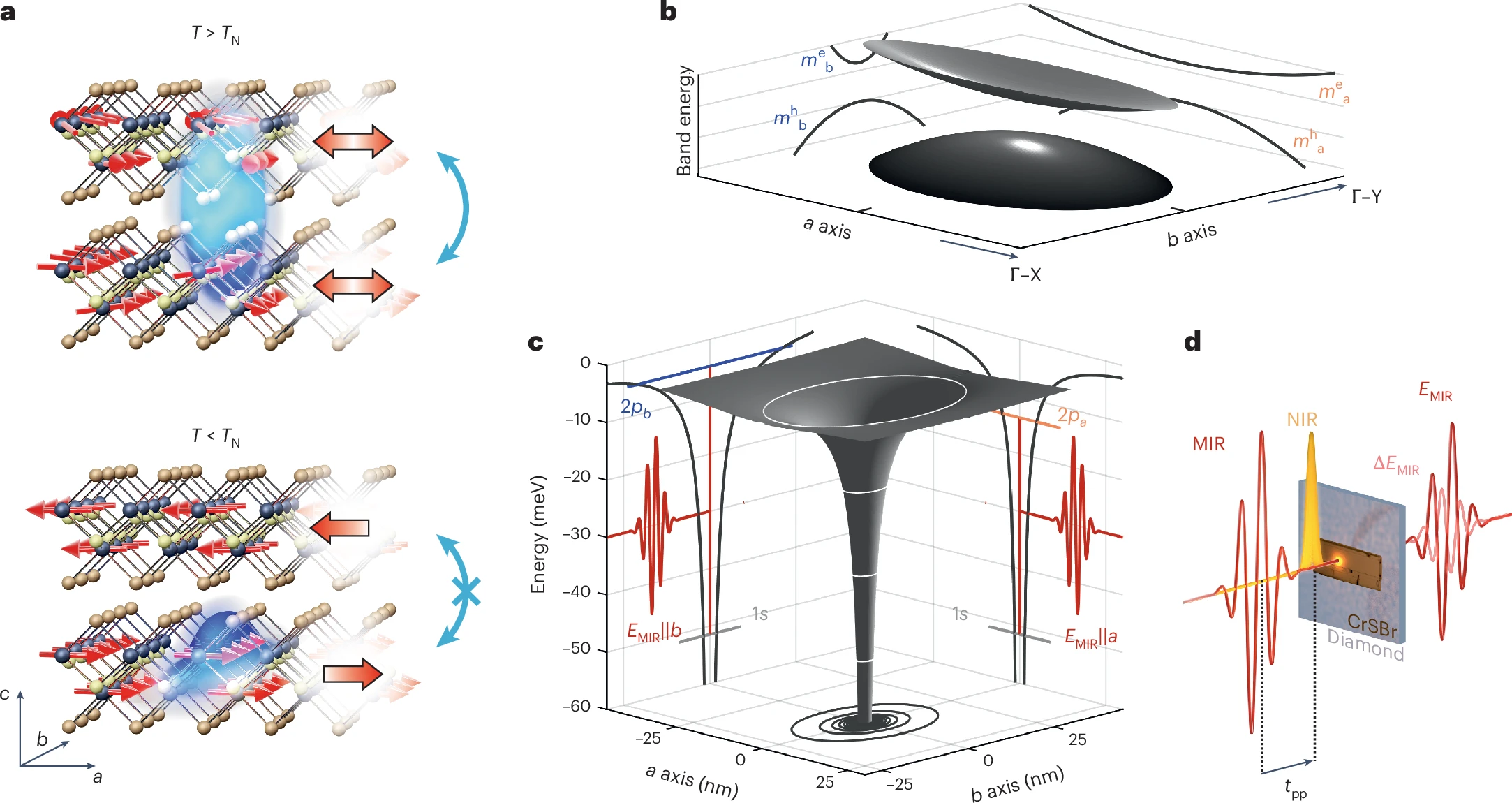

The researchers have demonstrated that quantum entities called excitons can be effectively confined to a single dimension within the material due to its unusual magnetic properties. This confinement could prolong the lifespan of quantum information carriers, reducing collisions and data loss. The material’s layers, just a few atoms thick, are magnetized at low temperatures, with electron spins aligning in an antiferromagnetic structure that switches direction from one layer to the next.

In the unmagnetized state, excitons extend over multiple atomic layers and can move in any direction. However, when the material is in its antiferromagnetic state, the excitons are confined to a single atomic layer and further restricted to a single line due to their ease of movement along one axis of the plane.

The team’s experiments involved creating excitons within a sample of chromium sulfide bromide using pulses of infrared light and nudging them into slightly higher energy states with less energetic pulses. They discovered two variations of the excitons with surprisingly different energies, a phenomenon known as fine structure. The researchers also probed the material’s inner structures by shooting the less energetic pulses along two different axes within the material.

The team plans to investigate whether these excitons, embodied in charge separation, can be converted to magnetic excitations embodied in electron spins. If successful, this would provide a valuable method for converting quantum information between the distinct worlds of photons, excitons, and spins.

The Quantum Frontier: Chromium Sulfide Bromide

This intriguing material is attractive to quantum researchers because it can support nearly any way information is physically encoded: electric charge, light (photons), magnetism (electron spins), and vibrations such as sound (phonons). The long-term vision is that future quantum machines or devices could utilize these properties, with photons transferring information, electrons processing it through their interactions, magnetism storing it, and phonons modulating and transducing it to new frequencies.

Excitons: Quantum Information Carriers

One method of encoding quantum information in chromium sulfide bromide is through excitons. An exciton forms when an electron is moved out of its “ground” energy state in the semiconductor into a higher energy state, leaving behind a “hole.” The electron and hole are paired together, forming an exciton. These excitons are trapped in single layers by chromium sulfide bromide’s unusual magnetic properties.

Magnetic Order: The Key to Trapping Excitons

At low temperatures below 132 Kelvin (-222 Fahrenheit), the material is magnetized, with the spins of the electrons aligning in an antiferromagnetic structure. This magnetic order confines excitons to a single atomic layer and further restricts them to a single dimension because they can easily move along only one plane axis. In a quantum device, this confinement helps quantum information last longer as the excitons are less likely to collide with one another and lose the information they carry.

Experimental Demonstration

The experimental team, led by Rupert Huber from the University of Regensburg, used various techniques to study these highly direction-dependent excitons. They found that their configurations could be adjusted based on the magnetic states, which can be switched through external magnetic fields or temperature changes.

The Interplay of Electronic, Photonic, and Spin Degrees of Freedom

The theoretical team, led by Matthias Florian from the University of Michigan, explained these results using quantum many-body calculations. They confirmed that the transition from one-dimensional to three-dimensional excitons accounted for the substantial changes observed in how long excitons could go without colliding. One of the big questions the team plans to pursue is whether these excitons embodied in charge separation can be converted to magnetic excitations embodied in electron spins. If it can be done, it would provide a useful avenue for converting quantum information between the very different worlds of photons, excitons, and spins.

External Link: Click Here For More