Quantum researchers at Cornell University and NTT Research announced a breakthrough in nonlinear photonics that could change the way optical devices are built and used. In a paper published this week in Nature, the team demonstrated a planar waveguide in which the second‑order optical nonlinearity, χ(2), can be reshaped across the chip at will. By applying a tailored electric field through a photoconductive layer and a spatial‑light pattern, the device can generate arbitrary two‑dimensional quasi‑phase‑matching (QPM) gratings on demand, allowing a single chip to perform a wide range of nonlinear functions that previously required dozens of bespoke devices.

How Electric Fields Enable Programmable Nonlinearity

The key to the new device is the conversion of a third‑order nonlinearity, χ(3), into a controllable second‑order response. In ordinary materials, χ(2) is fixed by crystal symmetry and cannot be switched on or off. The researchers instead exploit the electric-field-induced χ(2) effect, in which an applied bias field generates a second-order response proportional to the product of the field and the intrinsic third-order susceptibility. By patterning a photoconductive layer on top of the waveguide and illuminating it with a spatial‑light modulator, the team can locally alter the conductivity and thus the electric field distribution across the chip.

This approach offers a degree of parallelism that is impossible with conventional electrode patterns. Instead of a single, static array of electrodes, the photoconductive layer responds to the light pattern in real time, allowing the electric field, and consequently the χ(2) map, to be reshaped on the fly. The result is a programmable two‑dimensional χ(2) landscape that can be reconfigured in milliseconds, limited only by the response time of the photoconductive material and the speed of the spatial‑light modulator.

Breaking the One‑Device‑One‑Function Paradigm

Traditionally, nonlinear optical devices are engineered with a fixed QPM grating etched into the material during fabrication. Creating such gratings requires sophisticated nanofabrication techniques, such as domain inversion in ferroelectric crystals or orientation patterning in semiconductors. Each device is then locked into a single function, be it frequency conversion, pulse shaping, or quantum gate operation, and any deviation in operating conditions can degrade performance.

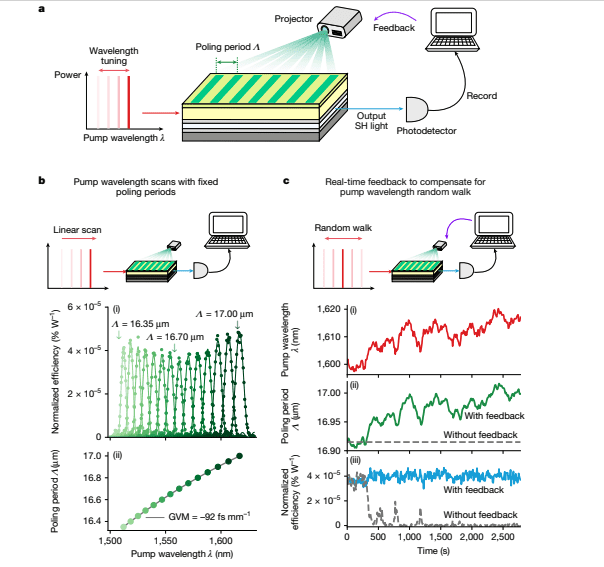

The programmable waveguide sidesteps these limitations entirely. Because the χ(2) distribution can be altered after fabrication, the same chip can be re‑designed in situ to perform different tasks. The researchers demonstrated inverse design of QPM gratings directly on the device, using computational algorithms to calculate the required χ(2) map for a target nonlinear process. They also showed that the device could adapt in real time to fluctuations in temperature or pump power, maintaining optimal phase‑matching without the need for manual retuning.

This flexibility transforms the industry’s approach to nonlinear optics. Instead of fabricating a new chip for each application, engineers can now program a single, high‑performance platform to meet the needs of a broad spectrum of optical systems.

Two‑Dimensional Quasi‑Phase‑Matching Gratings in Action

To illustrate the versatility of the platform, the team engineered a series of two‑dimensional QPM gratings that shaped the output of second‑harmonic generation (SHG) in unprecedented ways. By tailoring the χ(2) pattern across both the transverse (x) and longitudinal (z) dimensions of the waveguide, they achieved precise control over the spectral bandwidth, spatial profile, and spatio‑spectral characteristics of the generated light.

In one experiment, the researchers programmed a grating that produced a tightly focused SH beam with a spectral width narrowed to a few nanometres, while in another configuration they generated a broad, doughnut-shaped beam with a tunable spectral profile. These demonstrations highlight the ability to sculpt light not only in wavelength but also in shape and propagation direction, capabilities that are essential for advanced applications such as structured‑light imaging and quantum photonics.

The programmability also enables complex, hybrid QPM patterns that combine multiple nonlinear processes within the same device. For instance, a single waveguide can simultaneously perform frequency doubling and difference‑frequency generation, routing the output beams to distinct spatial channels, all controlled by a single, dynamic χ(2) map.

Real‑Time Adaptability for Quantum and Optical Applications

The implications of this technology extend far beyond laboratory demonstrations. In quantum photonics, fast reconfigurability is vital for building scalable quantum gates and sources of entangled photons. The programmable waveguide can generate entangled photon pairs on demand, adjust their spectral properties in real time, and compensate for environmental drift, all within a single chip.

All‑optical signal processing also stands to benefit. The ability to reshape nonlinear interactions on the fly means that optical routers, modulators, and switches can be reprogrammed to handle changing data streams without hardware changes. In optical computation, programmable χ(2) gratings could implement adaptive logic gates that respond to input signals dynamically, paving the way for neuromorphic photonic architectures.

Finally, adaptive structured light for sensing, such as LIDAR or biomedical imaging, could leverage the device’s capacity to generate custom beam shapes and spectra in real time, improving resolution and reducing noise in challenging environments.

The researchers note that the platform is compatible with existing photonic integration techniques, suggesting that it could be incorporated into commercial silicon‑photonic chips with minimal redesign. As the field moves toward fully reconfigurable optical systems, programmable nonlinear devices like this one will likely become a cornerstone of next‑generation photonic technology.

In summary, by harnessing electric‑field‑induced χ(2) and a massively parallel control scheme, Cornell and NTT researchers have unlocked a new dimension of flexibility in nonlinear optics. Their programmable waveguide turns a once‑fixed component into a dynamic, multi‑function platform that can adapt in real time to the demands of quantum information, optical communication, and beyond. As the technology matures, it promises to accelerate the deployment of versatile, high‑performance photonic devices across science and industry.