Led by Dr. Mostafa Mousa of the University of Oxford’s Department of Engineering Science, a team has developed a novel class of fully pneumatic, soft robots capable of synchronized locomotion without the need for conventional electronics, motors, or onboard computation. Published in Advanced Materials, the research details modular, air-powered components that integrate actuation, sensing, and logic within a single unit, enabling complex rhythmic movements achieved through physical interaction with the environment. This biomimetic approach demonstrates emergent synchronization—analogous to firefly flashing—and represents a significant advance towards self-regulating and adaptable robotic systems.

Air-Powered Robotics: Design and Mechanics

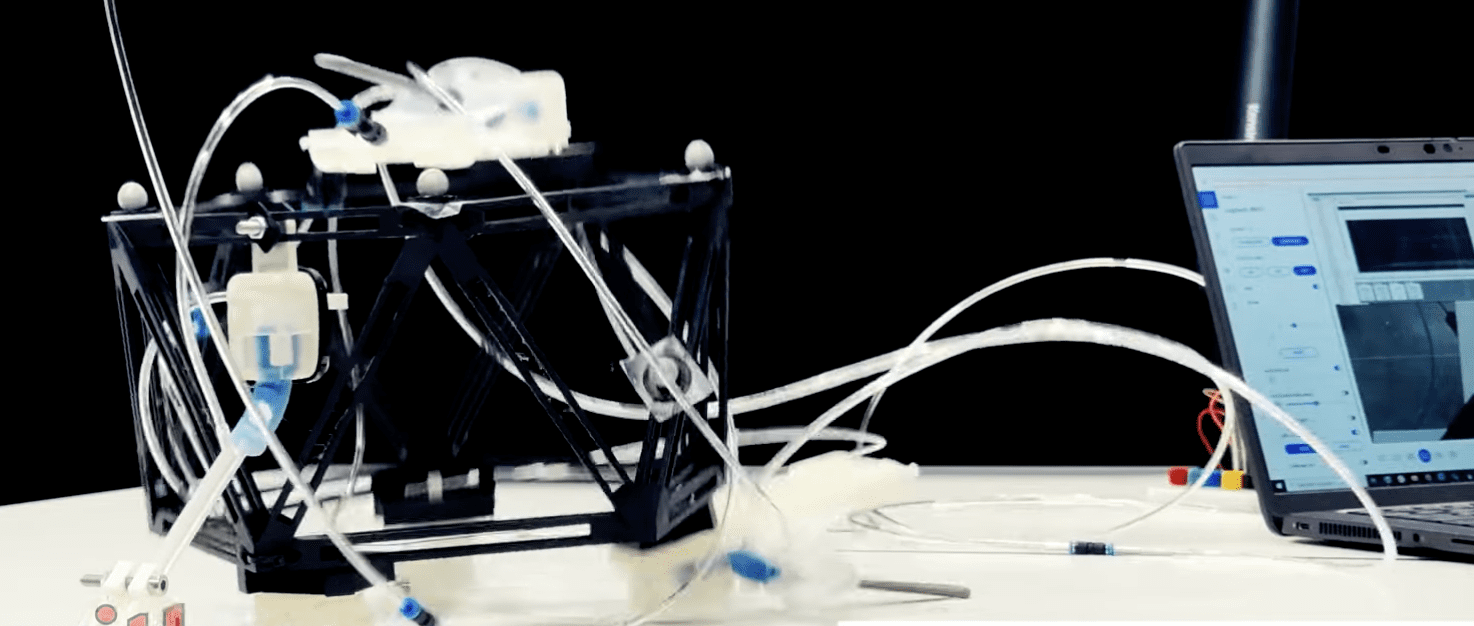

Air-powered robotics, developed at the University of Oxford, represents a departure from traditional designs relying on electronics and motors. These “fluidic robots” utilize small, modular units – just centimeters in size – that harness air pressure to actuate movement, sense contact, and function as logic gates. Crucially, a single unit can perform all three functions, enabling complex robot construction simply by connecting these identical blocks – similar to LEGOs. This design prioritizes mechanical simplicity over computational complexity.

The key innovation lies in achieving synchronized robotic movement without any computer control or programming. Researchers observed that when linked and grounded, these air-powered units naturally fall into rhythmic motion, mirroring how fireflies synchronize flashes. This behavior is explained by the Kuramoto model, highlighting how physical coupling and ground reaction forces create feedback loops that coordinate limb movements. The design is scale-independent, suggesting potential for larger deployments.

This approach promises faster, more efficient robots, particularly suitable for unpredictable environments. By encoding behaviour directly into the robot’s physical structure, the team is moving away from “robots with brains” toward robots as brains. Future research focuses on developing untethered, energy-efficient locomotors, potentially for deployment in extreme environments where adaptability and limited energy resources are paramount.

Emergent Synchronization Through Physical Interaction

Researchers at the University of Oxford have developed air-powered, “fluidic” robots capable of synchronized movement without traditional electronics or programming. These robots utilize modular units – each a few centimeters in size – that can actuate movement, sense pressure, and switch airflow, functioning like basic building blocks. By linking these units, researchers created tabletop robots that hop, shake, or crawl, demonstrating complex behavior emerging solely from physical design and air pressure – a significant leap towards truly adaptive robotics.

The key to this synchronization lies in physical interaction with the ground. When multiple robotic units are connected, their movements naturally align, explained by the Kuramoto model – a mathematical framework describing oscillator synchronization. Ground reaction forces and friction create a feedback loop, subtly influencing each limb and leading to spontaneous coordination. This means the robots don’t need external control; their behavior is intrinsically linked to their physical structure and the environment.

This approach contrasts with conventional robotics, shifting away from “robots with brains” towards machines embodying intelligence within their design. The design principles are scale-independent, paving the way for energy-efficient, untethered robots suitable for deployment in challenging environments where adaptability and limited power are crucial. The research, published in Advanced Materials, offers a pathway toward robots that react and coordinate without complex software or sensors.

Fluidic Unit Functionality: Sensing and Actuation

Fluidic units are revolutionizing soft robotics by enabling complex movement and sensing without traditional electronics. Researchers at Oxford University have developed modular components—just centimeters in size—that utilize air pressure to actuate movement (like a muscle), sense contact (like a touch sensor), or switch airflow (like a valve). This single, versatile unit can be linked with others to build diverse robots—from crawlers to shakers—demonstrating a shift towards robots where intelligence is embodied within their physical design, not reliant on external programming.

A key innovation is the robots’ ability to synchronize movements autonomously. When linked and grounded, these fluidic robots exhibit coordinated motion driven by physical interactions—ground reaction forces and friction—rather than computer control. Mathematical modeling using the Kuramoto model explains this synchronization, revealing that the robots’ design and environmental coupling create a feedback loop that naturally aligns their movements. This mimics emergent behaviors seen in nature, like fireflies flashing in unison.

These air-powered robots hold significant promise for deployment in challenging environments. The design principles are scale-independent, meaning the technology could be adapted for larger robots operating with limited energy resources. Future research focuses on creating untethered locomotors—robots that can move independently—potentially leading to adaptable machines for extreme environments where traditional robotics falters. The entire system is detailed in a recent Advanced Materials publication.

Potential Applications and Future Research

This research unlocks potential for truly adaptable robots, moving beyond reliance on complex programming and electronics. The team envisions scaling these fluidic robots – currently tabletop size – for deployment in challenging environments where energy is limited. Future work focuses on building untethered locomotors, meaning self-powered robots, capable of navigating extreme conditions. This scale-independence, combined with inherent robustness, positions the technology for applications like environmental monitoring in remote areas or search-and-rescue operations.

A key area for future research lies in refining the mathematical understanding of emergent synchronization. Using the Kuramoto model as a foundation, researchers aim to predict and control how these robots coordinate their movements based on physical design and environmental interaction. This could allow for the creation of robots with pre-defined collective behaviours without needing individual programming. Specifically, exploration into different unit geometries and material properties could unlock more complex and efficient coordinated motions.

Beyond locomotion, the modular nature of these fluidic units enables diverse applications. The researchers successfully demonstrated a bead-sorting robot and a cliff-edge detecting crawler. Future development could focus on creating robots capable of collaborative tasks – for example, a team of robots assembling structures or performing distributed sensing. Each unit’s ability to actuate, sense, and switch functions opens doors for intricate mechanical ‘logic’ systems, effectively embedding intelligence within the robot’s physical form.