Researchers at the University of Notre Dame have discovered that chronic compression—like that caused by brain tumors—directly triggers neuron death through a cascade of self-destructive processes. Published February 09, 2026, in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, the study reveals how physical pressure disrupts the brain’s intricate communication network, leading to potential sensory loss, motor impairment, and cognitive decline. The interdisciplinary team, led by Meenal Datta and Christopher Patzke, utilized induced pluripotent stem cells to model neuron behavior under pressure, finding that “for the neurons that are still alive, many of them have this programmed self-destruction signaling activated,” according to Patzke. This research lays crucial groundwork for identifying therapies to prevent neuron loss and mitigate the damaging effects of expanding tumors on brain tissue.

Chronic Compression Initiates Neuronal Self-Destruction Pathways

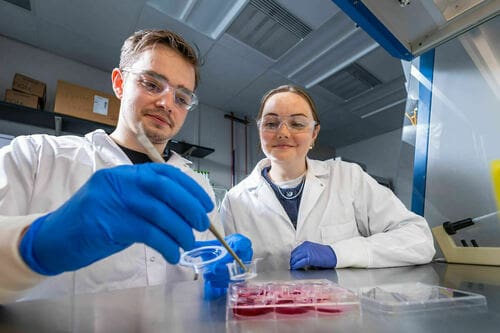

Researchers discovered that sustained physical pressure, such as that exerted by a growing brain tumor, doesn’t simply kill neurons directly, but also activates internal pathways triggering programmed cell death. Graduate students Maksym Zarodniuk and Anna Wenninger, working across labs, meticulously compared cell viability following simulated compression, revealing a significant proportion of surviving neurons exhibited signs of impending self-destruction. This model allowed precise control over compression levels, mimicking the forces exerted by glioblastoma, an aggressive brain cancer. Analysis of messenger RNA revealed a surge in HIF-1 molecules, signaling stress adaptation, but paradoxically leading to brain inflammation.

Further investigation identified increased expression of the AP-1 gene, indicating a neuroinflammatory response and confirming neuronal damage was underway. Data from the Ivy Glioblastoma Atlas Project corroborated these findings, demonstrating similar compressive stress patterns and gene expression changes in actual glioblastoma patients.

Datta emphasizes the often-overlooked role of mechanics in cancer progression: “In cancer research, most researchers are focused on the tumor itself, but in the meantime, while the tumor is sitting there and growing, it’s damaging the organ that it’s living in.” This research suggests potential therapeutic targets to mitigate neuronal loss, and may extend to other conditions involving mechanical brain trauma.

iPSC-Derived Neuronal Networks Model Glioblastoma Compression

Unlike traditional methods relying on fetal tissue, these iPSCs are generated by reprogramming readily available donor cells—blood or skin often collected during routine medical visits—allowing them to differentiate into any cell type, including neurons. This innovative system allows scientists to model the chronic compression exerted by glioblastoma, an aggressive and incurable brain cancer, and observe its impact on neuronal health. Further investigation showed the compression also triggered AP-1 gene expression, a neuroinflammatory response. Datta emphasizes the broader implications of this work, stating, “Our approach to this study was disease agnostic, so our research could potentially extend to other brain pathologies that affect mechanical forces in the brain such as traumatic brain injury.”

HIF-1 and AP-1 Gene Expression Indicate Neuronal Stress

The application of chronic pressure to brain tissue, as seen with tumor growth, initiates a cascade of molecular events within neurons indicating significant cellular stress, according to a study from the University of Notre Dame. Researchers discovered that even surviving neurons exhibit activation of programmed self-destruction signaling pathways following compression, prompting investigation into the underlying mechanisms. Detailed analysis of messenger RNA from affected cells revealed a marked increase in HIF-1 molecules, suggesting the activation of genes intended to bolster cell survival in stressful conditions, though ultimately contributing to brain inflammation.

The team utilized induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) to model this compression, allowing for precise control over the applied force and subsequent observation of cellular responses. Meenal Datta, co-lead author, emphasized the importance of considering mechanical forces, stating, “I’m all in on mechanics. Whatever it is that you’re interested in when it comes to cancer, above your question of interest, mechanics is sitting there and many don’t even know they should be considering it.”

For the neurons that are still alive, many of them have this programmed self-destruction signaling activated.

Glioblastoma Atlas Data Validates Compressive Stress Patterns

Unlike cells derived from fetal tissue, iPSCs were reprogrammed from donor blood or skin cells, functioning like embryonic stem cells. Further investigation pinpointed heightened expression of the AP-1 gene, a marker of neuroinflammation, confirming that neuronal damage was actively occurring.