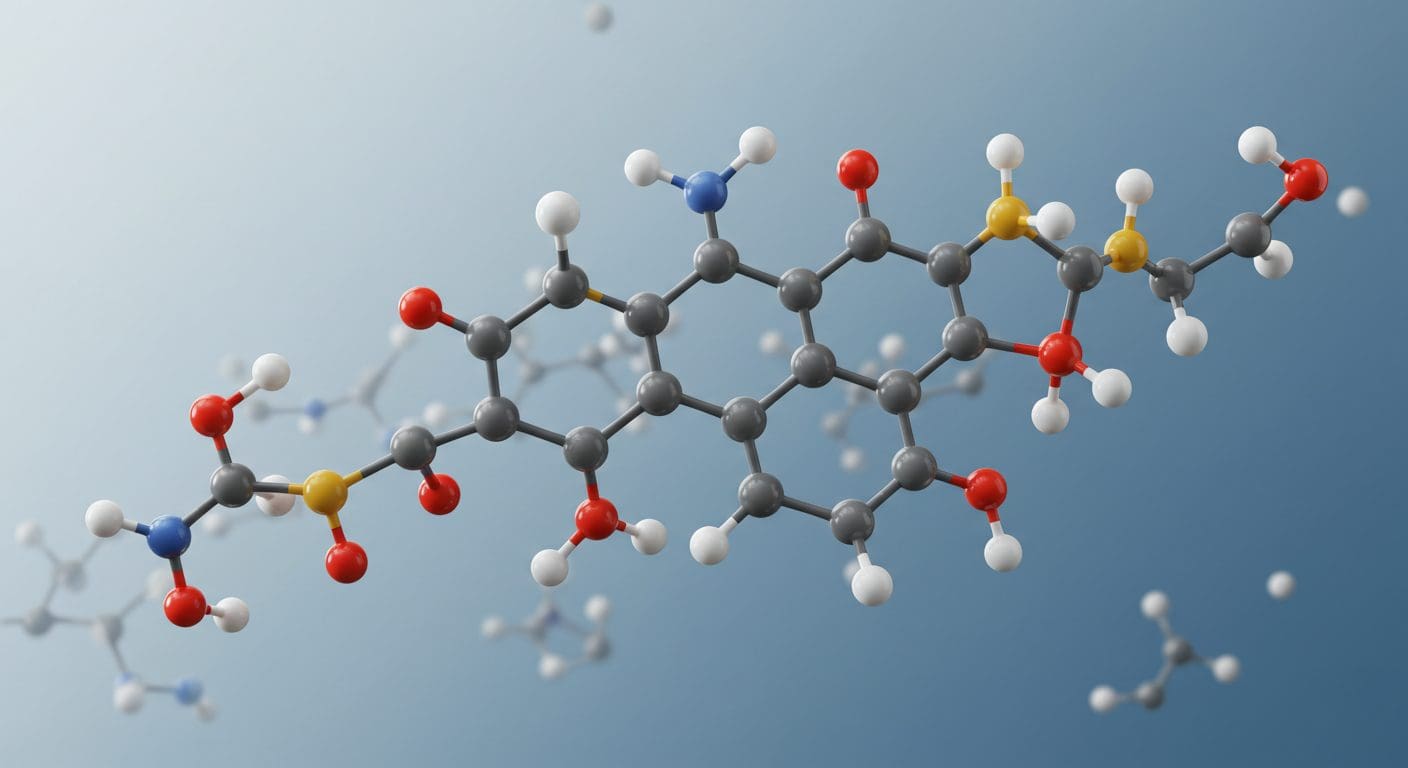

The pursuit of increasingly accurate molecular simulations drives the machine learning community to build ever-larger foundation models, hoping that scale alone will unlock transferable predictive power. Siwoo Lee from Princeton University’s Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering, along with Adji Bousso Dieng from the Department of Computer Science and colleagues, tested this assumption by scaling model capacity and training data using calculations of chemical properties. Their work focuses on predicting the bond dissociation energy of the simplest molecule, hydrogen. It reveals a surprising limitation: models trained solely on stable molecular structures perform poorly, even failing to capture the basic shape of the energy curve. Crucially, even the largest models, trained on extensive datasets, struggle to reproduce the fundamental repulsive energy curve expected from the interaction of two protons, suggesting that simply increasing scale does not guarantee reliable chemical modelling and a deeper understanding of underlying physical laws is essential.

Machine Learning Advances for Molecules and Materials

Research in machine learning is rapidly advancing the fields of chemistry and materials science, offering new tools for understanding and predicting the behavior of molecules and materials. This progress encompasses techniques like quantum machine learning, combining quantum chemistry principles with machine learning algorithms. Researchers are developing machine learning force fields, replacing traditional methods for calculating interatomic forces with models trained on quantum mechanical data. Neural networks, particularly convolutional and graph neural networks, are central to these efforts, proving effective for analyzing spatial and structural data inherent in molecular systems.

More recently, state-space models, like Mamba, are being explored for capturing long-range dependencies within molecular structures. Crucially, these networks are often designed to respect the symmetries present in molecules and materials, ensuring accurate and physically meaningful predictions. Specific architectures, such as Schnet and OrbNet, leverage these principles to model quantum interactions and symmetry-adapted atomic orbitals, while Spookynet incorporates electronic degrees of freedom for greater accuracy. The development of delta-machine learning offers a method for constructing models directly from quantum chemistry calculations.

Transfer learning and foundation models, such as Uma and Mattersim, are also gaining prominence, allowing researchers to apply knowledge gained from one dataset to another and create broadly applicable models. This work relies on large-scale datasets of molecular structures and properties, including databases like the GDB and QM9, and benchmarks like the Rowan Benchmarks, to train and evaluate these algorithms. These advancements are driving progress in materials discovery, atomistic simulation, and the prediction of material properties, ultimately accelerating the development of new technologies.

Scaling Neural Networks for Molecular Properties

Researchers investigated whether increasing the capacity of neural networks and the size of training datasets improves their ability to model chemical properties, focusing specifically on the bond dissociation energy of the hydrogen molecule. They employed datasets of quantum chemical calculations, systematically scaling both the number of training samples and the complexity of the neural network models. Performance was assessed on a hold-out test set, allowing researchers to determine whether larger models and more data led to improved predictions. To rigorously test the models’ understanding of fundamental chemical principles, the team focused on the bond dissociation energy curve of H₂, the simplest possible molecule.

Models were trained on datasets containing varying amounts of stable molecular structures, and then evaluated on their ability to predict the energy changes as the bond stretches and breaks. Recognizing that models might perform well on stable structures but struggle with bond dissociation, the researchers augmented the training data with non-ground-state structures, including those representing stretched and distorted geometries. This inclusion aimed to expose the models to a wider range of molecular configurations and assess their ability to extrapolate beyond the training data. A key aspect of the methodology involved training models on datasets exceeding 101 million structures, encompassing both stable and dissociating diatomic molecules.

This large-scale training was intended to determine whether increasing data volume could overcome limitations in the models’ ability to accurately describe bond dissociation. Crucially, the team also evaluated the models’ performance on the trivial case of two bare protons, a system governed solely by Coulomb’s law. This served as a fundamental test of whether the models had learned the basic physics underlying electronic structure theory, rather than simply memorizing patterns in the training data. The researchers then compared the models’ predictions to the analytically known energy curve derived from Coulomb’s law, providing a clear benchmark for assessing their understanding of fundamental physical principles.

Scaling Fails to Capture Hydrogen Bond Dissociation

This research demonstrates that simply increasing the size of neural networks and training datasets does not necessarily improve their ability to model quantum chemical systems, specifically the bond dissociation energy of the hydrogen molecule. Experiments reveal that even the largest foundation models, trained on datasets exceeding 101 million structures, consistently fail to accurately reproduce the bond dissociation curve of H₂, demonstrating a fundamental limitation in their ability to learn essential physics. Regardless of the quantity of training data or model capacity, the models exhibited no discernible improvement in predicting the H₂ bond dissociation energy, highlighting a critical gap between scaling and achieving physically meaningful results. The research team meticulously tested models trained on diverse datasets of equilibrium-geometry molecules, observing that increasing the number of training samples did improve performance on standard hold-out test sets.

However, this improvement did not translate to accurate predictions of the H₂ bond dissociation curve, even when models were trained with compressed and stretched geometries. More strikingly, the largest models completely failed to reproduce the simple repulsive energy curve for two bare protons, a system governed by the fundamental Coulomb’s law. This failure indicates that the models are not learning the underlying physical principles governing electronic structure, despite the massive scale of training data and model parameters. Further analysis demonstrated that the models’ inability to accurately predict the H₂ bond dissociation energy is not simply a matter of insufficient training data.

Even with the inclusion of non-ground-state structures in the training set, the models showed only modest improvement. The inability of these large foundation models to capture the basic physics of even the simplest diatomic molecule suggests that scaling alone is insufficient for building reliable quantum chemical models. These findings challenge the prevailing paradigm in the machine learning community that emphasizes scaling as a primary path toward improved generalization and raise important questions about the role of physical principles in the design of accurate and reliable models for quantum chemical systems.

Large Models Fail Quantum Chemistry Generalisation

This research demonstrates that simply increasing the size of neural network models and the amount of training data does not guarantee accurate predictions in quantum chemistry, even with chemically diverse datasets. The team investigated the ability of these large models to predict bond dissociation energies for the hydrogen molecule, a fundamental test case in chemistry. Results show that models trained solely on stable molecular structures fail to accurately reproduce even the basic shape of the energy curve, indicating a lack of generalizability. While including data from stretched and compressed geometries improves predictions, this improvement stems from exposure to these specific configurations rather than from learning underlying physical principles.

Notably, even the largest foundation models, trained on an extensive collection of quantum chemical calculations, exhibit significant deficiencies when predicting the behavior of simple diatomic molecules outside of equilibrium bonding regions. These models incorrectly predict the interaction between two protons, failing to accurately represent basic Coulomb’s law despite its potential inclusion as an inductive bias. This suggests that current large-scale models function primarily as data-driven interpolators, struggling to achieve true physical generalization. The authors acknowledge that alternative machine learning techniques, such as those correcting semi-empirical quantum chemistry methods or selecting minimal training data, may offer promising avenues for future research. Overall, this work highlights the need for new strategies to develop fast and accurate property predictions for novel molecules and materials, moving beyond the limitations of scaling alone.

👉 More information

🗞 Are neural scaling laws leading quantum chemistry astray?

🧠 ArXiv: https://arxiv.org/abs/2509.26397