Scientists at OpenAI and other firms are studying large language models (LLMs) by applying biological and neurological techniques. A 200-billion-parameter model, like OpenAI’s GPT4o released in 2024, could physically cover 46 square miles if printed on paper. This research aims to better understand these vast and complex machines and their potential limitations.

LLM Scale Visualized: 200 Billion Parameters & Beyond

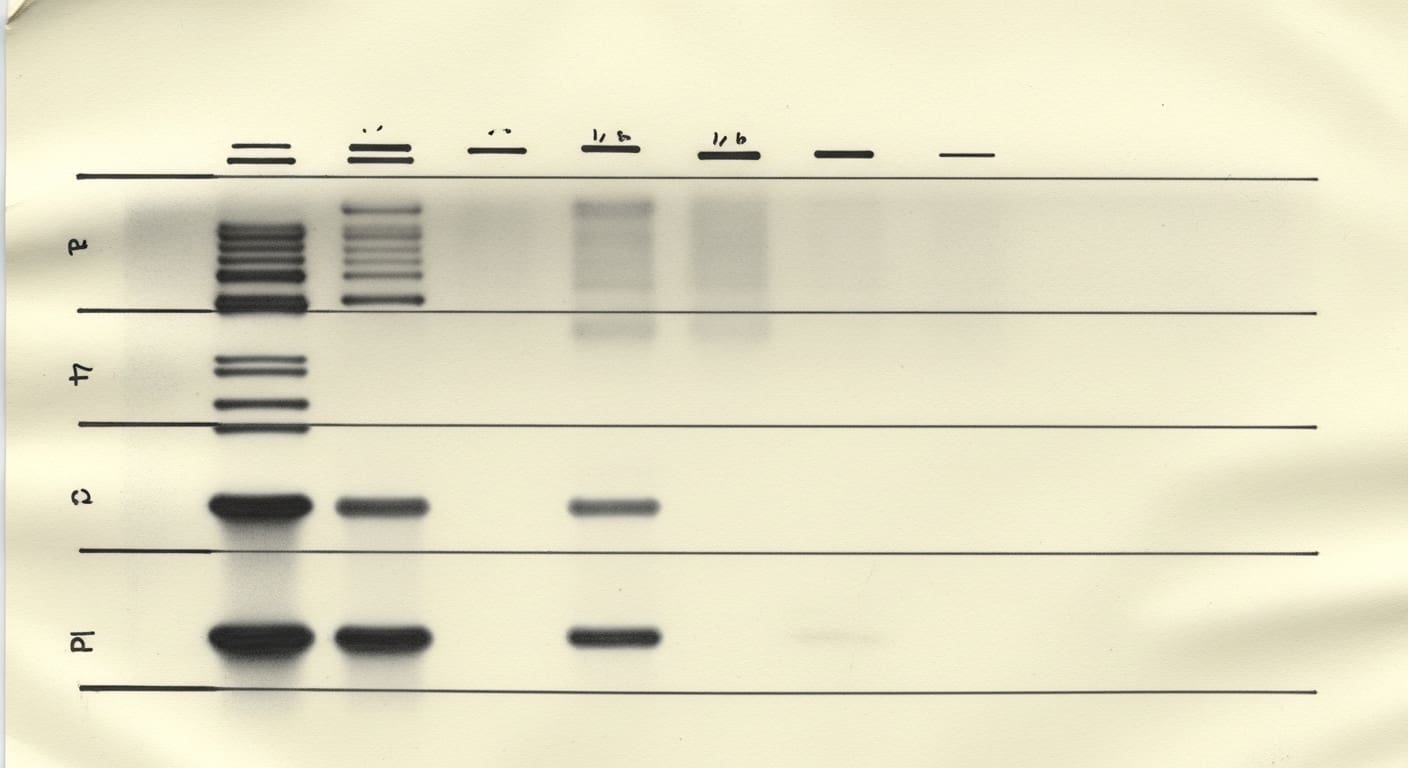

Visualizing the scale of large language models (LLMs) involves considering immense quantities of numerical data. A 200-billion-parameter model, such as GPT4o, would require 46 square miles of paper filled with numbers printed in 14-point type—an area roughly the size of San Francisco. Even larger models would necessitate an area comparable to the city of Los Angeles, illustrating the sheer complexity of these systems. Researchers are now using techniques like “mechanistic interpretability” to trace how information flows within LLMs, similar to brain scans. Anthropic developed sparse autoencoders—secondary, transparent models—to mimic primary LLMs and reveal internal processes.

For example, they pinpointed a region in Claude 3 Sonnet linked to the Golden Gate Bridge, demonstrating how specific parameters correlate to concepts and potentially influence responses.

“Growing” LLMs: Evolving Parameters Beyond Traditional Building

Large language models aren’t traditionally “built” but rather “grown” through automated training algorithms. These algorithms establish billions of numerical values, called parameters, with researchers having limited control over the specific configuration—similar to guiding the growth of a tree. Researchers are applying techniques mirroring biological analysis to understand LLM behavior, a field called mechanistic interpretability. Anthropic, for example, created sparse autoencoders—transparent secondary models—to mimic the responses of larger models, revealing internal pathways.

Mechanistic Interpretability Reveals Internal LLM Pathways

Researchers are employing “mechanistic interpretability” to investigate LLM pathways, treating the models like complex biological systems. This approach uses tools to trace activations—numbers calculated during operation—as they move through the model, revealing internal mechanisms similar to brain scans. Anthropic, for example, developed sparse autoencoders, secondary models trained to mimic larger LLMs, to make these pathways more visible and understandable. Through these techniques, researchers have discovered unexpected internal structures; one example showed a specific part of Anthropic’s Claude 3 Sonnet model associated with the Golden Gate Bridge.

Furthermore, studies reveal LLMs don’t simply know facts, but utilize distinct pathways to confirm correct statements versus deny incorrect ones, separating factual knowledge from truth assessment. This understanding is critical for improving alignment and predicting LLM behavior.

It doesn’t really feel like it’s going anywhere.

DeepMind’s Nanda

Sparse Autoencoders Decipher Claude 3 Sonnet’s “Golden Gate”

Anthropic utilized sparse autoencoders – secondary, transparent models – to investigate the inner workings of Claude 3 Sonnet. These autoencoders were trained to replicate Claude 3 Sonnet’s responses, providing a more interpretable window into the original model’s processes. Further investigation revealed that the model separates factual knowledge (“bananas are yellow”) from statements of truth (“Bananas are yellow” is true), potentially explaining inconsistencies in responses. This suggests LLMs don’t always process information as humans do, impacting expectations for reliable behavior.

Distinct Mechanisms for Truth & Falsehood in LLM Responses

Researchers are finding that LLMs utilize distinct mechanisms for processing truthful and false statements. Anthropic’s experiments with the Claude 3 Sonnet model revealed separate pathways activated when confirming a correct statement—bananas are yellow—versus denying an incorrect one—bananas are red. This suggests LLMs don’t simply verify information against existing knowledge, but employ different internal processes depending on the claim’s veracity. This discovery has implications for understanding inconsistencies in LLM responses; contradictions aren’t necessarily due to flawed logic, but rather the model drawing upon separate internal components.

Just as a book might present differing viewpoints on separate pages, the model accesses distinct “parts” for different assertions—a finding critical for improving model alignment and predicting behavior. This fundamentally changes expectations for how these systems process information and arrive at conclusions.