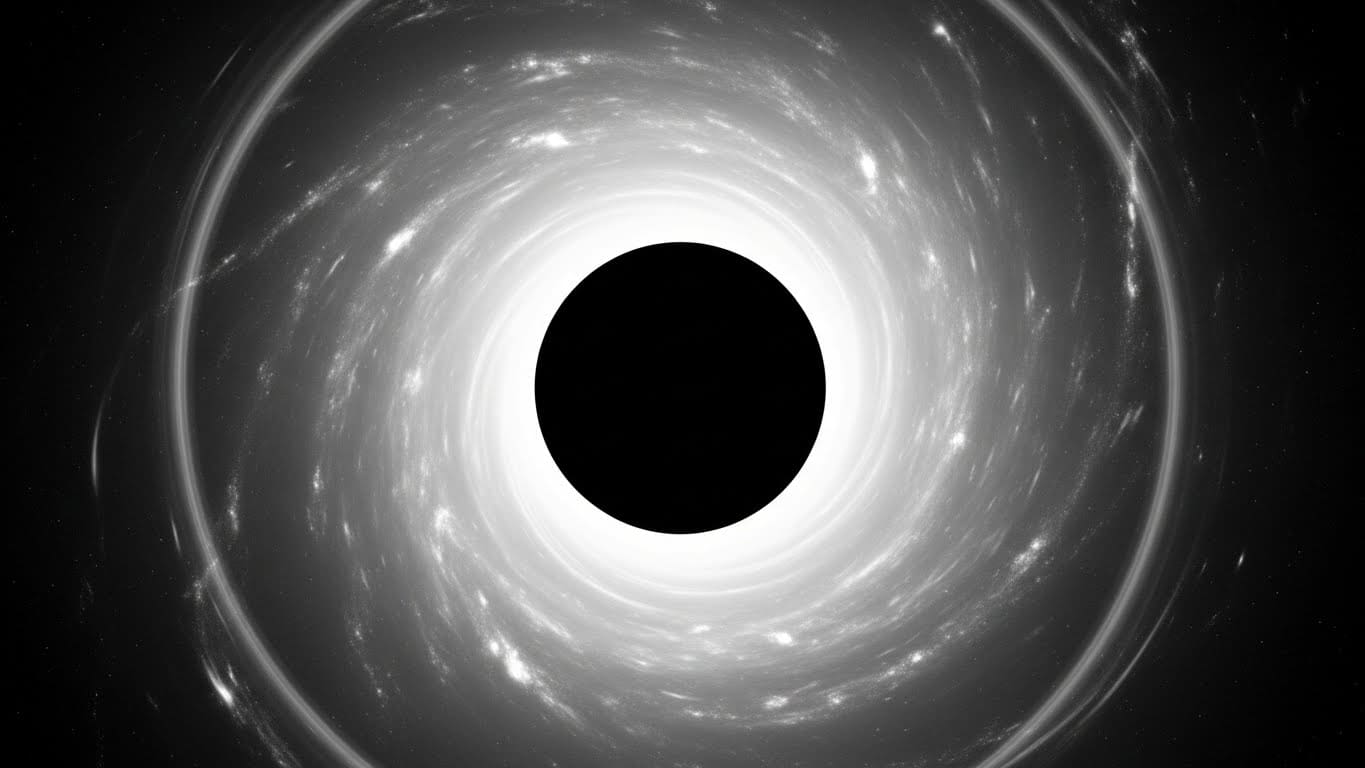

For decades, black holes were considered the ultimate cosmic vacuum cleaners, regions of spacetime so dense that nothing, not even light, could escape their gravitational pull. This picture, solidified by the work of physicists like Roger Penrose at Oxford University and Stephen Hawking at Cambridge University, painted a starkly absolute event horizon. However, in 1974, Stephen Hawking revolutionized our understanding, proposing that black holes aren’t entirely black. He theorized they emit a faint glow of radiation, now known as Hawking radiation, a phenomenon rooted in the bizarre marriage of quantum mechanics and general relativity. This radiation isn’t a leak from the black hole, but rather a creation at the event horizon, challenging the very definition of what a black hole truly is.

Hawking’s breakthrough stemmed from applying quantum field theory to the curved spacetime around a black hole. Quantum field theory, developed throughout the mid-20th century by physicists like Richard Feynman and Julian Schwinger, posits that even seemingly empty space isn’t truly empty, but rather teeming with virtual particles, fleeting pairs of particles and antiparticles that pop into existence and annihilate each other almost instantaneously. Near a black hole’s event horizon, these virtual pairs can be split apart by the intense gravity. One particle falls into the black hole, while the other escapes as real radiation, carrying away a tiny amount of the black hole’s mass-energy. This process, though incredibly slow for stellar-mass black holes, implies that black holes aren’t eternal, but gradually evaporate over immense timescales.

The Quantum Vacuum and the Event Horizon’s Edge

Understanding Hawking radiation requires grasping the concept of the quantum vacuum. This isn’t a void, but a dynamic state of minimum energy, constantly fluctuating with the creation and annihilation of virtual particles. These particles aren’t directly observable, existing only for a fleeting moment dictated by the Heisenberg uncertainty principle, formulated by Werner Heisenberg in 1927. This principle states that the more precisely one property of a particle is known, the less precisely another property can be known. This allows for temporary violations of energy conservation, giving rise to these virtual particle pairs. Now, consider this quantum activity occurring near the event horizon of a black hole. The extreme gravitational gradient warps spacetime, effectively providing the energy needed to make these virtual particles real.

The process isn’t a simple escape of particles from within the black hole. Instead, it’s a quantum tunneling effect. One particle of the virtual pair falls across the event horizon, becoming a real particle inside the black hole, while its partner escapes as Hawking radiation. This escaping particle appears to originate from the black hole itself, giving the impression of emission. Crucially, the energy for this escaping particle comes from the black hole’s mass. As the black hole radiates energy, it loses mass, shrinking ever so slightly. This is a profoundly important consequence, suggesting that black holes, once thought to be immutable, are subject to thermodynamic laws.

Temperature and the Black Hole’s Slow Demise

Hawking radiation isn’t a uniform burst of energy; it has a thermal spectrum, meaning it’s characterized by a specific temperature. This temperature, however, is inversely proportional to the black hole’s mass. For stellar-mass black holes, the temperature is incredibly low, on the order of a few nanokelvins, far colder than the cosmic microwave background radiation. This means that these black holes are currently absorbing more radiation from the universe than they are emitting, and are therefore growing, not shrinking. However, smaller, primordial black holes, theorized to have formed in the early universe, would have a higher temperature and could be actively evaporating.

The concept of a black hole having a temperature was a radical departure from classical physics. It implied that black holes aren’t simply “black bodies” that absorb all radiation, but rather objects with a defined thermodynamic state. This connection between gravity, quantum mechanics, and thermodynamics led to the development of black hole thermodynamics, a field pioneered by a researcher at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Stephen Hawking. Bekenstein proposed that black holes possess entropy, a measure of disorder, proportional to the area of their event horizon. Hawking then demonstrated that this entropy is directly related to the black hole’s temperature, establishing a complete set of laws governing black hole behavior analogous to the laws of thermodynamics.

The Information Paradox: A Challenge to Fundamental Laws

Hawking radiation, while theoretically elegant, presents a profound puzzle known as the information paradox. Quantum mechanics dictates that information, the precise quantum state of a system, can never be truly destroyed. However, Hawking radiation appears to be purely thermal, meaning it carries no information about the matter that originally formed the black hole. If a black hole completely evaporates via Hawking radiation, the information about its contents seems to vanish, violating a fundamental principle of quantum mechanics.

This paradox has spurred decades of research and debate. One proposed solution, championed by Leonard Susskind at Stanford University, involves the holographic principle. This principle suggests that all the information contained within a volume of space can be encoded on its boundary, like a hologram. In the context of black holes, the information about the infalling matter might be encoded on the event horizon itself, and then re-emitted in a scrambled form within the Hawking radiation. Another approach, developed by a researcher at the Institute for Advanced Study, Donald Harlow, and others, proposes that information isn’t lost, but rather escapes the black hole through subtle correlations within the Hawking radiation itself.

Testing the Theory: The Impossibility of Direct Observation

Despite its theoretical significance, directly observing Hawking radiation remains an insurmountable challenge with current technology. The temperature of stellar-mass black holes is far too low to produce detectable radiation against the background noise of the universe. Even for smaller black holes, the radiation would be incredibly faint and difficult to distinguish from other sources. Physicists are exploring indirect methods to test the theory, such as searching for subtle gravitational effects or looking for correlations in the radiation emitted by analogue black holes.

Analogue black holes are laboratory systems that mimic the properties of black holes, such as an event horizon. These systems, created using fluids or Bose-Einstein condensates, can exhibit similar phenomena to astrophysical black holes, allowing physicists to study Hawking radiation in a controlled environment. While these analogue systems aren’t perfect replicas of real black holes, they provide valuable insights into the underlying physics. Researchers, like Silke Weinfurtner at the University of Nottingham, are actively working on these experiments, hoping to provide evidence supporting Hawking’s predictions.

Beyond Black Holes: Implications for Quantum Gravity

The study of Hawking radiation extends far beyond the realm of black holes. It provides a crucial window into the elusive theory of quantum gravity, a framework that seeks to unify general relativity and quantum mechanics. These two pillars of modern physics, while incredibly successful in their respective domains, are fundamentally incompatible. General relativity describes gravity as a smooth curvature of spacetime, while quantum mechanics describes the universe as discrete and probabilistic.

Hawking radiation highlights the need for a theory that can reconcile these seemingly contradictory descriptions. Understanding the microscopic details of Hawking radiation could reveal the fundamental nature of spacetime at the Planck scale, the smallest possible unit of length. String theory, a leading candidate for a theory of quantum gravity, predicts that spacetime isn’t smooth, but rather composed of tiny vibrating strings. These strings could modify the behavior of Hawking radiation, potentially leaving observable signatures. The work of Juan Maldacena at Princeton University, connecting string theory to black hole thermodynamics through the AdS/CFT correspondence, has been particularly influential in this area.

The Persistence of the Paradox and Future Directions

The information paradox remains a central challenge in theoretical physics, driving ongoing research into the nature of black holes and quantum gravity. While several proposed solutions have emerged, none are universally accepted. The debate continues, fueled by new theoretical insights and experimental efforts. Physicists are exploring alternative models of black holes, such as fuzzballs and firewalls, which attempt to resolve the paradox by modifying the structure of the event horizon.

The future of Hawking radiation research lies in a combination of theoretical advancements and experimental ingenuity. Developing more sophisticated analogue black hole experiments, searching for subtle gravitational effects, and refining theoretical models are all crucial steps towards unraveling the mysteries of these enigmatic objects. As our understanding of quantum gravity deepens, we may finally be able to fully comprehend the faint glow of the abyss and the ultimate fate of black holes, confirming or refuting Hawking’s groundbreaking prediction and solidifying our understanding of the universe’s most extreme environments.