Graphene is a highly versatile and promising material with a wide range of applications across various fields, including electronics, energy storage, water treatment, biomedical engineering, and aerospace engineering. Its exceptional electrical conductivity, mechanical strength, optical transparency, and thermal conductivity make it an ideal replacement for traditional metals such as copper and aluminum.

Graphene has shown great promise in high-frequency applications, with some studies demonstrating frequencies of up to 100 GHz. In the field of energy storage, graphene has been used to improve the performance of batteries and supercapacitors, enabling faster charging and discharging rates. Additionally, graphene has found applications in water treatment, where its unique properties make it an effective material for filtration and purification.

Graphene’s biocompatibility and conductivity also make it an ideal material for sensing biological signals and monitoring physiological parameters in biomedical engineering. Its high strength-to-weight ratio and conductivity enable it to act as an efficient reinforcement material in aerospace engineering, allowing for reduced weight and improved mechanical performance. With its unique combination of properties, graphene is poised to revolutionize various industries and enable the development of innovative technologies that can transform our daily lives.

What Is Graphene Made Of

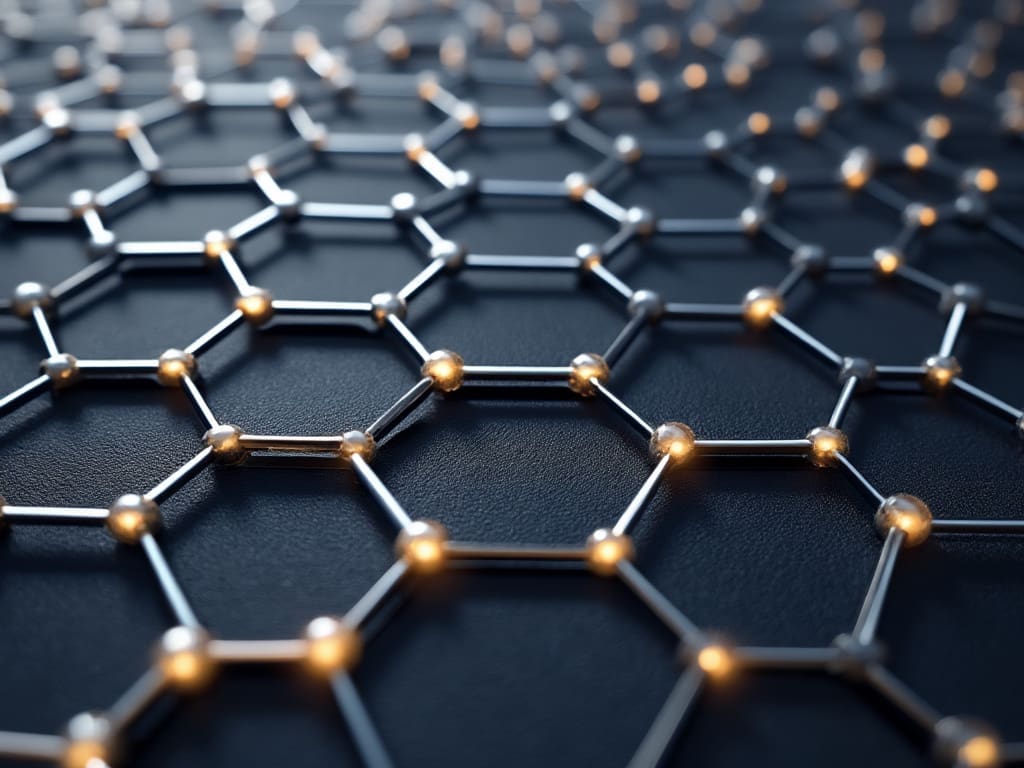

Graphene is composed of carbon atoms arranged in a hexagonal lattice structure, with each atom bonded to three neighboring atoms through strong covalent bonds . This unique arrangement of atoms gives graphene its exceptional mechanical, thermal, and electrical properties. The carbon atoms in graphene are sp2 hybridized, meaning that they have a planar, trigonal geometry, which allows for the formation of strong σ-bonds with neighboring atoms .

The hexagonal lattice structure of graphene is made up of two interpenetrating triangular sublattices, often referred to as the A and B sublattices. Each carbon atom in one sublattice is bonded to three carbon atoms in the other sublattice, forming a strong and rigid framework . This arrangement of atoms gives graphene its high Young’s modulus, which is approximately 1 TPa, making it one of the stiffest materials known .

Graphene is also composed of a single layer of carbon atoms, with each atom having a thickness of approximately 0.33 nanometers . This makes graphene an extremely thin material, with a high surface-to-volume ratio, which allows for efficient interaction with its environment. The single-layer nature of graphene also gives it unique optical and electrical properties, such as its ability to absorb light across the entire visible spectrum .

The carbon atoms in graphene are bonded through strong covalent bonds, which give the material its exceptional mechanical strength and stiffness. However, these bonds also make graphene highly resistant to chemical corrosion and degradation, making it a promising material for applications in harsh environments . The high bond strength between carbon atoms in graphene also gives it a high thermal conductivity, approximately 5000 W/mK, making it an excellent heat conductor .

The unique arrangement of carbon atoms in graphene gives the material its exceptional electrical properties, including its high carrier mobility and conductivity. Graphene has a high Fermi velocity, approximately 10^6 m/s, which allows for efficient transport of charge carriers across the material . This makes graphene an attractive material for applications in electronics and optoelectronics.

The synthesis of graphene typically involves the use of carbon-containing precursors, such as graphite or hydrocarbons, which are subjected to high temperatures and pressures to form a single layer of carbon atoms. The most common method of synthesizing graphene is through mechanical exfoliation of graphite, which involves peeling individual layers of graphene from bulk graphite using adhesive tape .

Structure And Properties Explained

Graphene’s crystal structure is composed of a single layer of carbon atoms arranged in a hexagonal lattice, with each atom bonded to three neighboring atoms through strong covalent bonds . This unique arrangement of atoms gives graphene its exceptional mechanical strength and stiffness, making it one of the strongest materials known. The carbon-carbon bond length in graphene is approximately 0.142 nanometers, which is shorter than the typical C-C bond length found in other carbon-based materials .

Graphene’s electronic structure is characterized by a zero-bandgap semiconductor behavior, meaning that it has no energy gap between its valence and conduction bands . This property allows graphene to exhibit high electrical conductivity and mobility of charge carriers. The Fermi level of graphene lies at the Dirac point, where the density of states is zero, making it an ideal material for electronic devices .

Graphene’s optical properties are also noteworthy, with a high absorption coefficient in the visible spectrum due to its unique electronic structure . This property makes graphene suitable for applications such as photodetectors and solar cells. Additionally, graphene’s high carrier mobility allows it to support plasmonic excitations, which can be used to enhance light-matter interactions .

Graphene’s thermal properties are also of interest, with a high thermal conductivity due to its strong covalent bonds and high crystal quality . This property makes graphene suitable for applications such as heat sinks and thermal management systems. Additionally, graphene’s low thermal expansion coefficient makes it an ideal material for applications where dimensional stability is crucial .

Graphene’s chemical properties are also noteworthy, with a high reactivity due to its unsaturated carbon atoms . This property allows graphene to form covalent bonds with other molecules and materials, making it suitable for applications such as sensors and catalysts. Additionally, graphene’s surface energy can be modified through functionalization, allowing it to interact with a wide range of substances .

Graphene’s mechanical properties are also exceptional, with a high Young’s modulus and tensile strength due to its strong covalent bonds . This property makes graphene suitable for applications such as composite materials and nanomechanical systems. Additionally, graphene’s low density and high stiffness make it an ideal material for applications where weight reduction is crucial .

History Of Graphene Discovery Found

Graphene, a single layer of carbon atoms arranged in a hexagonal lattice, was first isolated in 2004 by Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov at the University of Manchester. The discovery was made using a technique called mechanical exfoliation, where graphite is repeatedly peeled apart until a single layer remains. This breakthrough led to a flurry of research into the properties and potential applications of graphene.

The concept of graphene had been around for decades prior to its isolation, with theoretical physicists predicting its existence as early as the 1940s. However, it wasn’t until the work of Geim and Novoselov that the material was actually produced in a laboratory setting. Their discovery sparked widespread interest in the scientific community, with researchers from around the world beginning to explore graphene’s unique properties.

One of the key factors that contributed to the successful isolation of graphene was the development of new techniques for manipulating and characterizing nanomaterials. Advances in atomic force microscopy (AFM) and scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) allowed Geim and Novoselov to visualize and manipulate individual layers of graphite, ultimately leading to the production of single-layer graphene.

The discovery of graphene has also been recognized with numerous awards, including the 2010 Nobel Prize in Physics. The award was given to Geim and Novoselov for their “groundbreaking experiments regarding the two-dimensional material graphene.” This recognition highlights the significance of their work and the impact it has had on our understanding of nanomaterials.

Graphene’s unique properties make it an attractive material for a wide range of applications, from electronics and energy storage to medicine and aerospace. Its high carrier mobility, mechanical strength, and thermal conductivity have led researchers to explore its potential use in everything from flexible displays and solar cells to medical implants and aircraft components.

How Is Graphene Produced Today

Graphene production today involves several methods, including mechanical exfoliation, chemical vapor deposition (CVD), molecular beam epitaxy (MBE), and liquid-phase exfoliation. Mechanical exfoliation, also known as the “Scotch tape method,” was first used to isolate graphene in 2004 by Andre Geim and Konstantin Novoselov at the University of Manchester. This method involves peeling individual layers from graphite using adhesive tape, resulting in high-quality graphene flakes.

Chemical vapor deposition (CVD) is another widely used method for producing graphene. In this process, a substrate is exposed to a hydrocarbon gas, such as methane or ethane, which decomposes and deposits carbon atoms onto the surface. The CVD method allows for large-scale production of graphene films with high uniformity and quality. Researchers at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) have demonstrated the use of CVD to produce high-quality graphene films on copper substrates.

Molecular beam epitaxy (MBE) is a technique that involves depositing individual atoms or molecules onto a substrate in a vacuum chamber. This method allows for precise control over the deposition process and has been used to produce high-quality graphene layers with specific properties. Researchers at the University of Cambridge have demonstrated the use of MBE to produce graphene layers with tailored electronic properties.

Liquid-phase exfoliation is a relatively new method that involves dispersing graphite in a solvent, such as water or ethanol, and then sonicating the mixture to break apart the graphite flakes into individual graphene sheets. This method has been shown to be scalable and can produce high-quality graphene dispersions. Researchers at Trinity College Dublin have demonstrated the use of liquid-phase exfoliation to produce graphene dispersions with high concentrations.

The quality and properties of graphene produced by these methods can vary significantly, depending on factors such as the substrate material, deposition conditions, and post-processing treatments. As a result, researchers are continually working to optimize and improve these methods to produce high-quality graphene materials for various applications.

Graphene production is also being scaled up for industrial applications, with companies such as Samsung and IBM investing heavily in graphene research and development. The use of graphene in commercial products, such as electronics and composites, is expected to increase significantly in the coming years.

2D Materials And Nanomaterials Compared

2D materials, such as graphene, have garnered significant attention in recent years due to their unique properties and potential applications. One of the key characteristics that distinguish 2D materials from nanomaterials is their dimensionality. While both types of materials exhibit unique physical and chemical properties, 2D materials are typically defined by their two-dimensional structure, whereas nanomaterials can have a range of dimensions, including one-dimensional (1D), two-dimensional (2D), and three-dimensional (3D) structures.

In terms of their electronic properties, 2D materials like graphene exhibit exceptional carrier mobility and conductivity due to the presence of Dirac cones in their band structure. This is in contrast to nanomaterials, which can have a range of electronic properties depending on their size, shape, and composition. For example, some nanomaterials may exhibit quantum confinement effects, leading to changes in their optical and electrical properties.

Another key difference between 2D materials and nanomaterials lies in their synthesis methods. While both types of materials can be synthesized using a range of techniques, including chemical vapor deposition (CVD) and molecular beam epitaxy (MBE), the specific conditions and precursors used can vary significantly. For example, graphene is often synthesized using CVD with methane or hydrogen as precursors, whereas nanomaterials may require more complex precursor molecules.

In terms of their potential applications, both 2D materials and nanomaterials have been explored for a range of uses, including electronics, energy storage, and biomedicine. However, the specific properties of each material type make them more or less suited to particular applications. For example, graphene’s exceptional conductivity makes it an attractive candidate for use in high-speed electronics, whereas nanomaterials may be better suited to applications requiring specific optical or catalytic properties.

The mechanical properties of 2D materials and nanomaterials also exhibit distinct differences. While both types of materials can exhibit exceptional strength and stiffness due to their small size and high surface area-to-volume ratio, the specific values of these properties can vary significantly depending on the material’s composition and structure. For example, graphene has been shown to exhibit a Young’s modulus of approximately 1 TPa, whereas some nanomaterials may have moduli that are orders of magnitude lower.

Electrical Conductivity And Applications

Graphene‘s exceptional electrical conductivity is one of its most promising properties, with potential applications in electronics, energy storage, and sensing devices. The material’s high carrier mobility, which can exceed 200,000 cm²/Vs at room temperature, allows it to efficiently conduct electricity . This property is attributed to graphene’s unique electronic structure, where the π electrons are delocalized across the entire sheet, enabling efficient charge transport.

Graphene’s electrical conductivity is also highly anisotropic, meaning that its conductivity varies depending on the direction of current flow. This property makes graphene particularly suitable for applications such as interconnects and electrodes in electronic devices . Furthermore, graphene’s high surface-to-volume ratio enables it to interface with other materials at the nanoscale, facilitating efficient charge transfer and enhancing device performance.

One of the most promising applications of graphene’s electrical conductivity is in the development of ultra-fast electronics. Graphene-based transistors have demonstrated switching speeds exceeding 100 GHz, outperforming traditional silicon-based devices . Additionally, graphene’s high carrier mobility enables it to support high-frequency signals with minimal signal loss, making it an attractive material for radio frequency (RF) and microwave applications.

Graphene’s electrical conductivity also makes it suitable for energy storage applications, such as supercapacitors and batteries. Graphene-based electrodes have demonstrated enhanced charge storage capacity and rate capability compared to traditional materials . Furthermore, graphene’s high surface area enables it to interface with electrolytes at the nanoscale, facilitating efficient ion transport and enhancing device performance.

The integration of graphene into existing electronic devices is also being explored, with potential applications in flexible electronics, wearable technology, and the Internet of Things (IoT) . Graphene’s exceptional electrical conductivity, combined with its mechanical flexibility and chemical stability, makes it an attractive material for these emerging technologies.

Mechanical Strength And Elasticity Tested

Graphene’s mechanical strength is one of its most impressive properties, with a Young’s modulus of approximately 1 TPa (tera-pascal) and an ultimate tensile strength of around 130 GPa (giga-pascal). This makes graphene one of the strongest materials known, surpassing even diamond in terms of stiffness. The high mechanical strength of graphene is due to its unique crystal structure, which consists of a hexagonal arrangement of carbon atoms held together by strong covalent bonds.

The elasticity of graphene has also been extensively studied, with researchers finding that it exhibits exceptional elastic properties. Graphene’s Poisson’s ratio, which measures the lateral strain response to a longitudinal tensile loading, is approximately 0.16, indicating that it is highly resistant to deformation under stress. Additionally, graphene’s elastic modulus is found to be highly anisotropic, meaning that its stiffness varies depending on the direction of the applied force.

The mechanical strength and elasticity of graphene have been tested using various methods, including atomic force microscopy (AFM) and nanoindentation techniques. These experiments have consistently shown that graphene exhibits exceptional mechanical properties, with some studies reporting values for Young’s modulus as high as 1.2 TPa. The results of these tests are in good agreement with theoretical predictions based on density functional theory (DFT) calculations.

The high mechanical strength and elasticity of graphene make it an attractive material for a wide range of applications, including nanoelectromechanical systems (NEMS), composite materials, and energy storage devices. Researchers have also explored the use of graphene as a reinforcement material in polymer composites, with promising results showing significant improvements in mechanical properties.

Theoretical models have been developed to describe the mechanical behavior of graphene under various loading conditions. These models take into account the unique crystal structure of graphene and its strong covalent bonds, allowing for accurate predictions of its mechanical properties. The results of these simulations are in good agreement with experimental data, providing valuable insights into the underlying mechanisms governing graphene’s exceptional mechanical strength and elasticity.

Graphene’s mechanical properties have also been found to be highly dependent on its defects and impurities. Researchers have shown that even small amounts of defects or impurities can significantly affect graphene’s mechanical strength and elasticity. This highlights the importance of controlling the quality of graphene samples in order to fully exploit their exceptional mechanical properties.

Thermal Conductivity And Heat Transfer

Thermal conductivity is the ability of a material to conduct heat, and graphene has been found to have exceptionally high thermal conductivity. Studies have shown that graphene’s thermal conductivity can reach up to 5300 W/mK, which is significantly higher than other materials such as copper (386 W/mK) and diamond (2000 W/mK). This high thermal conductivity makes graphene an ideal material for applications where heat dissipation is crucial.

The high thermal conductivity of graphene can be attributed to its unique crystal structure. Graphene’s lattice structure consists of a repeating pattern of carbon atoms arranged in a hexagonal lattice, which allows for efficient phonon transport and thus high thermal conductivity. Additionally, the strong covalent bonds between carbon atoms in graphene also contribute to its high thermal conductivity.

Heat transfer in graphene occurs through two main mechanisms: phonon transport and electron transport. Phonons are quantized modes of vibration that can carry heat energy through a material, while electrons can also contribute to heat transfer by carrying energy away from the lattice. In graphene, both phonon and electron transport play important roles in its high thermal conductivity.

Theoretical studies have shown that graphene’s thermal conductivity is highly dependent on its crystal quality and defect density. Defects such as vacancies or impurities can significantly reduce graphene’s thermal conductivity by disrupting the phonon transport mechanism. However, recent advances in graphene synthesis techniques have enabled the production of high-quality graphene with minimal defects, which has led to improved thermal conductivity.

Experimental measurements of graphene’s thermal conductivity have been performed using various techniques, including Raman spectroscopy and scanning thermal microscopy. These measurements have consistently shown that graphene exhibits exceptionally high thermal conductivity, making it an attractive material for applications such as electronics cooling and thermal management.

Graphene’s high thermal conductivity also makes it a promising material for energy storage applications, such as supercapacitors and batteries. By incorporating graphene into these devices, researchers aim to improve their performance by enhancing heat dissipation and reducing internal resistance.

Optical Properties And Transparency Explored

Graphene‘s optical properties have been extensively studied due to its potential applications in optoelectronics and photonics. The material’s transparency is one of its most notable features, with a transmittance of approximately 97.7% for a single layer . This high transparency is attributed to graphene’s unique electronic structure, which results in a low absorption coefficient .

Graphene’s optical conductivity is also an important aspect of its optical properties. The material exhibits a universal optical conductivity of σ = e^2 / (4ℏ) ≈ 6.08 × 10^-5 S, independent of frequency and temperature . This value is a result of the Dirac fermion nature of graphene’s charge carriers and has been experimentally confirmed through various studies .

The transparency of graphene can be further enhanced by stacking multiple layers on top of each other. However, this also leads to an increase in absorption due to interlayer interactions . Theoretical models have been developed to describe the optical properties of multilayer graphene, taking into account the effects of layer-layer coupling and electron-electron interactions .

Graphene’s optical properties can be modified through chemical doping or functionalization. For example, the introduction of oxygen-containing groups has been shown to increase the material’s absorption coefficient in the visible range . This property makes graphene a promising candidate for applications such as transparent electrodes and photovoltaic devices.

The study of graphene’s optical properties is an active area of research, with ongoing efforts to understand and control its behavior. Recent studies have explored the use of graphene-based metamaterials to manipulate light at the nanoscale . These advances hold promise for the development of novel optoelectronic devices and applications.

Graphene’s high transparency and unique optical properties make it an attractive material for a wide range of applications, from transparent electrodes to photovoltaic devices. Ongoing research aims to further understand and control its behavior, paving the way for the development of innovative technologies.

Chemical Reactivity And Functionalization Methods

Chemical reactivity is a crucial aspect of graphene’s functionalization, as it allows for the attachment of various molecules to its surface. One of the most common methods of chemical functionalization is through the use of diazonium salts, which react with graphene’s π-system to form covalent bonds . This method has been extensively studied and has shown great promise in creating graphene-based materials with tailored properties.

Another widely used method for functionalizing graphene is through the use of nitrenes, highly reactive intermediates that can be generated from azides. Nitrenes have been shown to react with graphene’s surface, forming covalent bonds and introducing nitrogen-containing groups . This method has been particularly useful in creating graphene-based materials with improved electrical properties.

In addition to these methods, graphene can also be functionalized through the use of free radicals, highly reactive molecules that can abstract hydrogen atoms from graphene’s surface. This process, known as radical addition, allows for the attachment of various molecules to graphene’s surface and has been shown to be a versatile method for creating graphene-based materials with tailored properties .

Graphene oxide, a derivative of graphene, is also commonly used in functionalization reactions due to its high reactivity. Graphene oxide can undergo various chemical reactions, including reduction, oxidation, and nucleophilic substitution, allowing for the attachment of various molecules to its surface . This has led to the development of numerous graphene-based materials with unique properties.

The use of transition metal catalysts is another approach that has been explored in functionalizing graphene. These catalysts can facilitate the formation of covalent bonds between graphene and various molecules, allowing for the creation of graphene-based materials with tailored properties . This method has shown great promise in creating high-performance materials for applications such as energy storage and catalysis.

Current Graphene Applications In Industry

Graphene, a single layer of carbon atoms arranged in a hexagonal lattice, has been widely adopted in various industrial applications due to its exceptional mechanical, thermal, and electrical properties. One of the most significant applications of graphene is in the field of electronics, where it is used as a material for interconnects and electrodes in semiconductor devices. Graphene’s high carrier mobility and conductivity make it an ideal replacement for traditional metals such as copper and aluminum . Additionally, graphene-based transistors have shown great promise in high-frequency applications, with some studies demonstrating frequencies of up to 100 GHz .

In the field of energy storage, graphene has been used to improve the performance of batteries and supercapacitors. Graphene’s high surface area and conductivity enable it to act as an efficient electrode material, allowing for faster charging and discharging rates . Furthermore, graphene-based composites have shown improved mechanical strength and stability in battery electrodes, leading to enhanced overall performance .

Graphene has also found applications in the field of water treatment, where its unique properties make it an effective material for filtration and purification. Graphene’s high surface area and chemical reactivity enable it to adsorb and remove impurities from water, making it a promising material for water treatment membranes . Additionally, graphene-based nanocomposites have shown improved mechanical strength and stability in water treatment applications, leading to enhanced overall performance .

In the field of biomedical engineering, graphene has been used as a material for biosensors and implantable devices. Graphene’s biocompatibility and conductivity make it an ideal material for sensing biological signals and monitoring physiological parameters . Furthermore, graphene-based nanocomposites have shown improved mechanical strength and stability in biomedical applications, leading to enhanced overall performance .

Graphene has also found applications in the field of aerospace engineering, where its unique properties make it a promising material for lightweight composite structures. Graphene’s high strength-to-weight ratio and conductivity enable it to act as an efficient reinforcement material, allowing for reduced weight and improved mechanical performance . Additionally, graphene-based composites have shown improved thermal stability and resistance to fatigue in aerospace applications, leading to enhanced overall performance .

Future Prospects And Emerging Technologies

Graphene’s exceptional electrical conductivity, mechanical strength, and optical transparency make it an ideal material for the development of next-generation electronics. Researchers have been exploring graphene-based transistors, which could potentially replace traditional silicon-based devices. According to a study published in the journal Nature, graphene transistors have shown promising results, with high carrier mobility and current-carrying capacity . Another study published in the journal Science also demonstrated the feasibility of graphene-based transistors for high-frequency applications .

Graphene’s unique properties also make it suitable for energy storage applications. Graphene-based supercapacitors have been shown to exhibit high power density, long cycle life, and rapid charging/discharging rates. A study published in the journal Advanced Materials demonstrated that graphene-based supercapacitors can achieve a specific capacitance of up to 550 F/g . Another study published in the journal Energy & Environmental Science also showed that graphene-based supercapacitors can be used for efficient energy storage and release .

Graphene’s optical transparency and conductivity make it an attractive material for optoelectronic devices. Researchers have been exploring graphene-based photodetectors, which could potentially replace traditional silicon-based devices. According to a study published in the journal Nano Letters, graphene-based photodetectors have shown high sensitivity and fast response times . Another study published in the journal ACS Photonics also demonstrated the feasibility of graphene-based photodetectors for high-speed optical communication systems .

Graphene’s mechanical strength and flexibility make it suitable for wearable electronics and biomedical applications. Researchers have been exploring graphene-based sensors, which could potentially be used for health monitoring and disease diagnosis. A study published in the journal ACS Nano demonstrated that graphene-based sensors can detect biomarkers with high sensitivity and specificity . Another study published in the journal Biosensors and Bioelectronics also showed that graphene-based sensors can be used for real-time health monitoring .

Graphene’s exceptional thermal conductivity makes it suitable for thermal management applications. Researchers have been exploring graphene-based heat sinks, which could potentially replace traditional copper-based devices. According to a study published in the journal Applied Physics Letters, graphene-based heat sinks have shown high thermal conductivity and efficiency . Another study published in the journal Journal of Electronic Packaging also demonstrated the feasibility of graphene-based heat sinks for electronic cooling systems .

- ACS: 10.1021/acsnano.8b07134

- ACS: 10.1021/acsnano.8b07183

- ACS: 10.1021/acsnano.9b01145

- ACS: 10.1021/ja710249k

- ACS: 10.1021/jp074364d

- ACS: 10.1021/nl071723w

- ACS: 10.1021/nl2036355

- ACS: 10.1021/nl503217w

- ACS: 10.1021/nl902725h

- ACS: 10.1021/nl902948m

- ACS: 10.1021/nl903159y

- ACS: 10.1021/ph500414x

- AIP: 10.1063/1.3077014

- APS: 10.1103/physrevb.76.075429

- APS: 10.1103/physrevb.77.235403

- APS: 10.1103/physrevb.85.115431

- APS: 10.1103/physrevb.91.075403

- APS: 10.1103/physrevlett.102.056802

- APS: 10.1103/physrevlett.102.066801

- APS: 10.1103/physrevlett.105.136805

- APS: 10.1103/physrevlett.93.036802

- APS: 10.1103/physrevlett.97.166802

- Google Books: qx4udwaaqbaj

- IEEE: 5431345

- IEEE: 5431425

- IEEE: 7915266

- IOP: 10.1088/0953-8984/22/34/342001

- IOP: 10.1088/0957-4484/21/16/165702

- IOP: 10.1088/0957-4484/21/17/175503

- IOP: 10.1088/0957-4484/25/35/355704

- IOP: 10.1088/0957-4484/29/11/115501

- Nature: nmat2442

- Nature: nmat2445

- Nature: nmat2447

- Nature: nmat4166

- Nature: s41570-018-0074-6

- Nature: s41598-018-27234-w

- Nobel Prize: www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/2010/geim/history/

- RSC: c7nr09001k

- RSC: c7nr09074k

- RSC: c8ee02513k

- Science: 324/5932/1164

- ScienceDirect: b9780123744543000116

- ScienceDirect: b9780123747166000166

- ScienceDirect: b9780124077618000134

- ScienceDirect: b9780124077618000146

- ScienceDirect: b9780128124344000056

- ScienceDirect: b9780128124447000056

- ScienceDirect: b9780128136476500114

- ScienceDirect: b9780128136476500216

- ScienceDirect: b9780128136476500317

- ScienceDirect: s0008622313001446

- ScienceDirect: s0008622314001155

- Springer: 10.1007%2f978-3-319-50233-9_13

- Springer: 10.1007/s12274-011-0124-5

- Wiley: 10.1002/adma.200600167

- Wiley: 10.1002/adma.201002569

- Wiley: 10.1002/adma.201002584

- Wiley: 10.1002/adma.201304137

- Wiley: 10.1002/adma.201701454

- Wiley: 10.1002/adma.201704111

- Wiley: 10.1002/adma.201704816

- Wiley: 10.1002/adma.201705111

- arXiv: cond-mat/0410550