Scientists are tackling the growing energy demands of artificial intelligence by exploring physics-based approaches to machine learning. Qingshan Wang, Clara C. Wanjura, and Florian Marquardt, from the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Light and University of Erlangen-Nuremberg, investigated how network architecture impacts the success of equilibrium propagation, a promising physics-based training method. Their research moves beyond theoretical studies of simple, fully connected networks to examine the performance of more practical, locally connected lattices. By training an XY model, they demonstrate that sparse networks can achieve comparable results to dense networks, offering crucial insights for designing scalable and energy-efficient artificial intelligence systems.

Sparse Local Networks Mimic Dense Performance with fewer

In the last decade, Artificial neural networks (ANN) have proven their capability in addressing complex tasks that are out of the reach of conventional algorithms. However, along with the astonishing achievements of ANNs, the amount of energy consumed to support the computational demands required by modern artificial intelligence (AI) applications has grown rapidly. This motivates the study of neuromorphic computing, where one explores the training of physical systems that could replace conventional digital ANNs. Specifically, in neuromorphic computing one views physical systems as information-processing machines, considers some of their degrees of freedom as input and output, and updates trainable parameters to achieve the desired input-output mapping.

For each neuromorphic platform, one has to figure out suitable Methods to do inference and training. Many examples of neuromorphic systems have by now been explored. Even early developments in machine learning like the Hopfield network and the Boltzmann machine already had a direct connection to (statistical) physics and were even experimentally implemented [3, 5]. Nowadays, neuromorphic platforms more generally range from optical systems to solid state systems like spintronics or arrays of memristors, and from coupled oscillators to mechanical networks. However, training neuromorphic systems is challenging.

Training a physical network is fundamentally different from training conventional ANNs, which can simply rely on the mathematical algorithm of backpropagation. Physical neural networks either have to be trained in simulation or the training has to rely on physics-based training Methods which only exist for certain classes of systems. In the past few years, several techniques for the efficient training of neuromorphic devices have been proposed, explored, and partially already implemented (for a review see). Examples include physics-aware training (a hybrid technique combining backpropagation in simulation with physical inference), forward-forward training which optimizes layer activations locally [12, 13], variations of contrastive learning (e. g. ), and a variety of approaches addressing optical neural networks: back-propagation through the linear components, training updates via physical backpropagation relying on particular nonlinearities [16, 17], gradients extracted via scattering in situations where nonlinear processing is achieved in linear setups, a recently introduced general approach for scattering-based training in arbitrary nonlinear optical setups, and Hamiltonian Echo Backpropagation with training updates based on physical dynamics.

While optical devices operate far out of equilibrium, there is also the possibility to exploit interacting equilibrium systems as a neuromorphic platform. In this domain, one observes the system after equilibration under constraints given by the current input. For this wide range of systems, i. e. energy-based models, there is a powerful approach for the physics-based extraction of training gradients, namely Equilibrium Propagation (EP). Over time, several variations of EP have been proposed and implemented, such as coupled learning. Various extensions, e. g. to vector fields, to Lagrangian systems [24, 25], and for more accurate gradients [26, 27], have been presented.

Furthermore, autonomous parameter updates driven by physical interactions have been explored [26, 28, 29]. Recently, EP has even been extended to quantum many-body systems [30, 32]. In terms of applications to possible physical scenarios, up to now, EP and its extensions have been explored numerically for Hopfield-like models, linear electrical resistor networks, nonlinear resistive networks, and coupled oscillators [34, 35]. In experiments, EP has successfully been applied to linear resistive networks [9, 36, 37], but other platforms such as Ising models have been considered as well. In the present paper, we investigate the effect of network architecture on the expressivity and performance of networks trained with EP.

This is crucial, since physical implementations often operate under constraints such as local connectivity, different from the convenient theoretical assumption of all-to-all connectivity. In particular, we focus on the XY model as a prototypical nonlinear model that can be trained using EP. We expect many of our qualitative Results to generalize to other models. Our analysis thereby contributes to the important issue of scaling up EP-based architectures in realistic settings. These two types of architecture are of a general type and experimentally feasible.

We then investigate the effect of system size using the Iris dataset and compare the outcomes with those obtained from training all-to-all connected networks and layered networks with dense connectivity. Notably, in contrast to all-to-all and dense-layer architectures, a lattice contains significantly fewer couplings, all of which are local. This comparison thus reveals the extent to which couplings can be reduced while preserving the functional capacity of the network. Finally, the role of architectural choices of the hidden layers in layered networks is studied by comparing the performance of different networks on full-size MNIST.

Brief Review of Equilibrium Propagation. In this section, we briefly review equilibrium propagation (EP), a method for extracting approximate parameter gradients of a cost function in physical networks. EP assumes a physical network modeled as an energy-based model (EBM) in the context of supervised learning. The network energy is denoted by E({x}, θ), where {x} represents the network configuration and θ the trainable parameters. In EP, E is referred to as the internal energy function.

We consider a system composed of multiple nodes. Some nodes are designated as input nodes, whose states are fixed during evolution to the steady state, while others are output nodes, whose steady-state configurations define the network output. Supervised learning requires an additional energy function C(xout, yτ) describing the interaction between the output and the target yτ. The total energy is then F(x; θ) = E(x, θ) + βC(xout, yτ). During the training, the steady states are obtained by solving the following ODE with β = 0 in the free phase and β = 0 in the nudged phase: φi = −∂F/∂φi = −∂E/∂φi −β∂C/∂φi.

Training is performed using equilibrium propagation [21, 34]. For each architecture, we initialize the lattice with 100 different initial sets of couplings and with zero bias fields. During the training, the performance is assessed with the following distance function, again following: D(φ, φτ) = 1/4 Σ |si − sτ i |2 = 1/2 Σ 1 − cos(φi − φτ i). Throughout all numerical experiments, we set β = 0.1. In this paper, we investigate the XY model across different architectures, employing the training method introduced in to address the issue of multistability.

We focus on XY models of different coupling architectures. The definition of internal energy E and external energy C are the same as in: E = − Σ Wij cos(φi − φj) − Σ i hi cos(φi − ψi) and C = Σ i∈O −log(1 + cos(φi − φτ i)) in which O refers to all the output nodes, ⟨i, j⟩refers to a coupled pair of nodes, and hi and ψi refer to the amplitude and direction of a local bias field. Evolution of the Network Response. Since we are most interested in locally connected architectures, it is of particular importance to understand the response of such architectures to local perturbations, since this determines the transport of information and, as we will see, eventually the success of training.

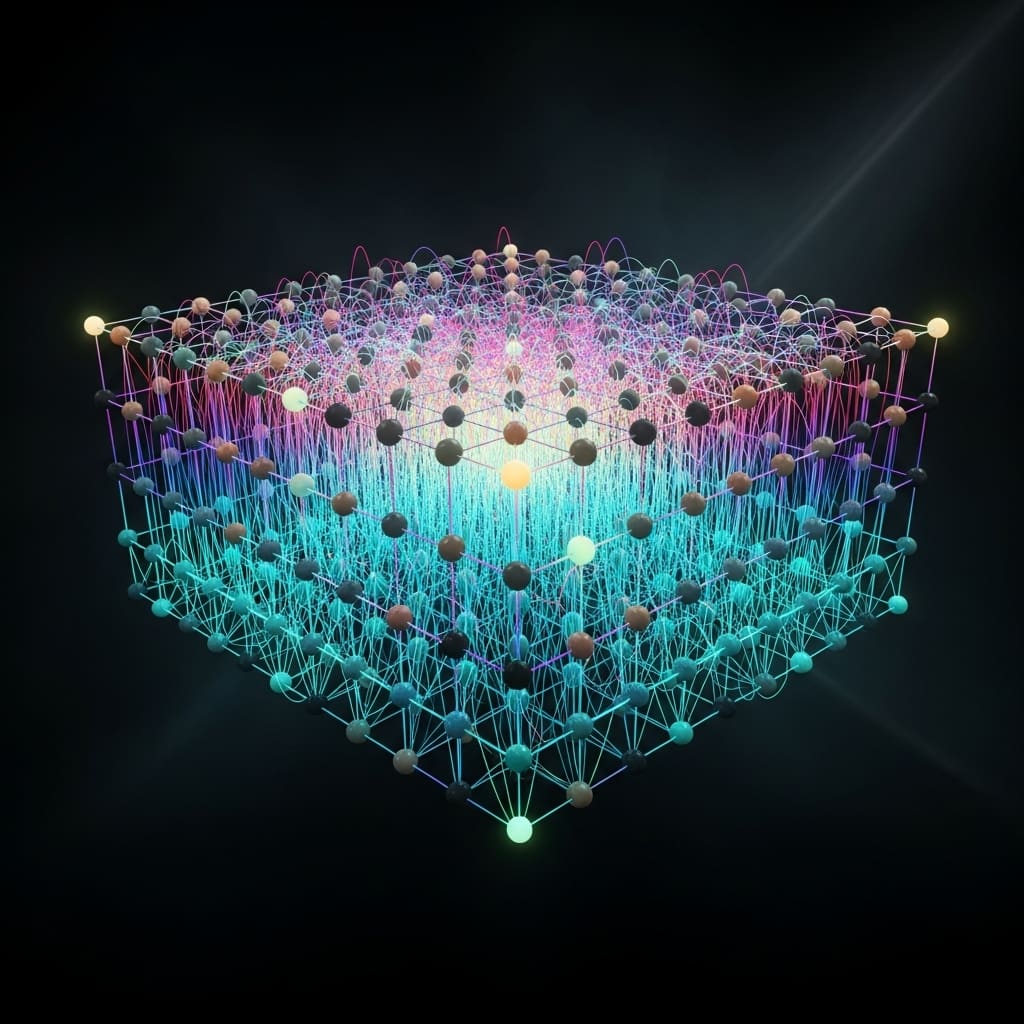

In this section, we therefore study the network response; for illustration, we chose the particular task of training the XOR function. We find that the evolution of the network structure can be described in terms of both response and coupling strength, which collectively reveal a division of the system into an affected region, sensitive to input perturbations, and a marginal region, largely inactive. We introduce the four different lattice architectures shown in Fig0.1 (a) that differ in their connectivity. As shown in Fig0.1 (b), the input and output nodes are placed near the central region of a 15 × 15 lattice with no direct connections between them.

Specifically, in our numerical experiments, the input nodes are located at (6, 6) and (7, 10), while the output node is at (10, 8), where (x, y) denotes the node in the x-th row and y-th column. The encoding protocol of true and false is shown on the right of Fig0.1 (b). The learning rate is chosen as η = 0. To mitigate the effect of multistability, networks are randomly initialized and run five times per epoch for each data sample (Minit = 5). We found that for the given architecture trained on the XOR task, training with an additional nudging force at the free equilibrium (as discussed in the Appendix of Ref. ), which is slightly different from standard EP at finite β, Results in a higher convergence probability and less fluctuations in the loss function. Fi,nudged,XOR = −∂C/∂φi (φfree out ) = − sin(φfree i,out − φτ) / (1 + cos).

Sparse lattices match dense network performance with fewer

Scientists are addressing the escalating energy consumption associated with the rapid advancement of artificial intelligence. Experiments revealed that locally connected lattices maintain functional capacity despite having significantly fewer couplings than all-to-all or densely connected architectures. The team measured performance on the XOR task, a standard benchmark for nonlinear computation, and subsequently extended the analysis to the Iris dataset to assess the impact of system size. Data shows that the XY model, when trained with equilibrium propagation, exhibits robust performance across varying network scales and connectivity patterns.

Scientists recorded the evolution of network responses and trainable couplings, providing insights into the learning dynamics within these physical systems. The research highlights the potential for creating energy-efficient neuromorphic computing systems by leveraging sparse connectivity and physics-based training algorithms. Tests prove that equilibrium propagation effectively trains these networks, enabling them to perform complex tasks with reduced computational demands. The breakthrough delivers a pathway towards more sustainable artificial intelligence by demonstrating the feasibility of training sparse, locally connected networks.

Researchers analysed stacked lattices with local inter-layer connections, further validating the effectiveness of this architectural approach. Findings suggest that the number of couplings can be substantially reduced without compromising the network’s ability to perform nonlinear computations, offering a crucial step towards scalable and energy-efficient neuromorphic hardware. This study establishes a foundation for future investigations into the optimisation of network architectures for physics-based training methods.

Sparse lattices rival dense networks performance in certain

The findings reveal that CNN-like networks perform best with a given number of trainable parameters, while locally connected lattices outperform traditional digital networks with the same parameter count. Introducing longer skip connections enhances the network’s ability to maintain long-range responses, improving performance and fostering self-organization within the lattice structure. Although training lattices remains more challenging than training all-to-all networks, requiring more epochs for comparable results on tasks like XOR, lattices can still match or surpass the performance of densely connected layered networks, particularly with the inclusion of skip connections. The authors acknowledge that training lattices is more computationally demanding than training fully connected networks, as evidenced by the longer training times observed for certain tasks. Future research could explore methods to accelerate lattice training and investigate the potential of these architectures in more complex learning scenarios.

👉 More information

🗞 Dependence of Equilibrium Propagation Training Success on Network Architecture

🧠 ArXiv: https://arxiv.org/abs/2601.21945