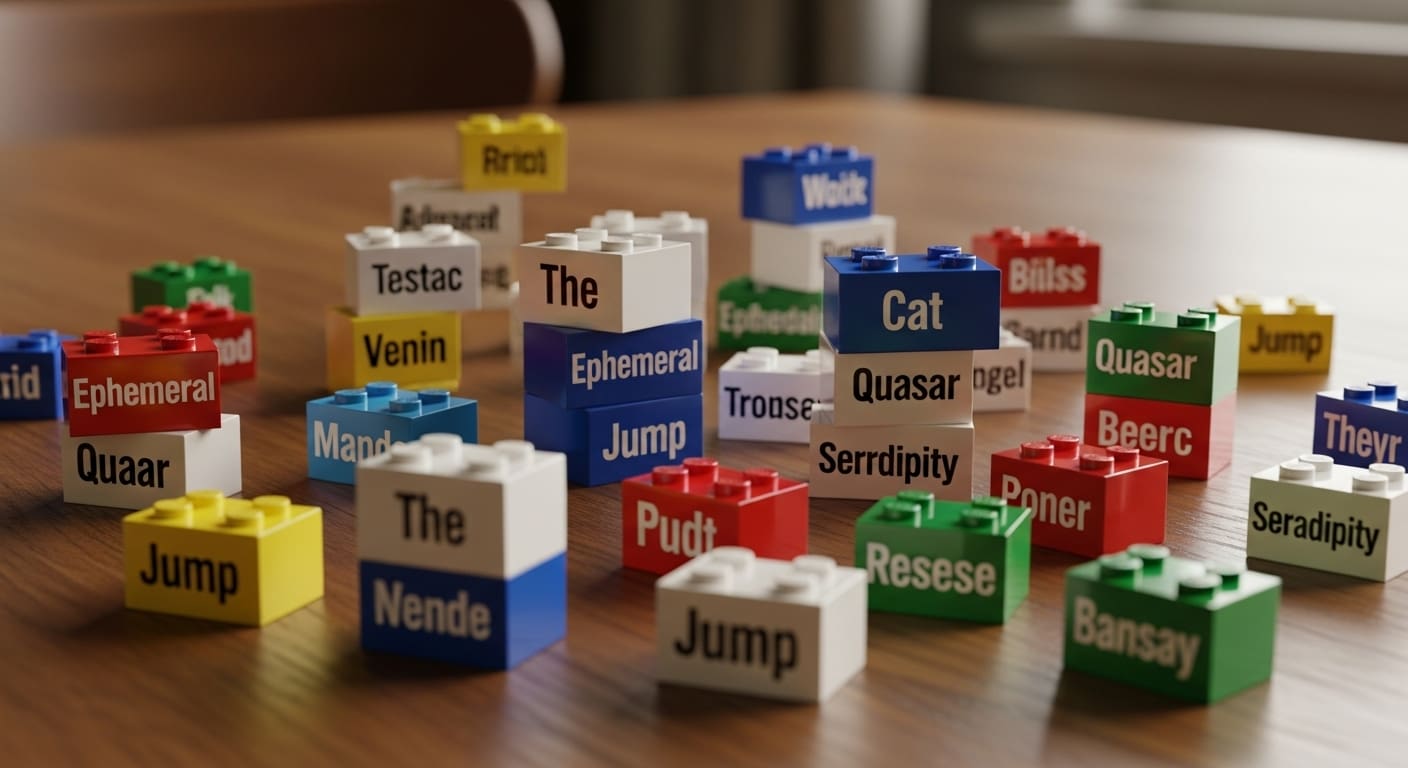

Cornell University researchers are challenging decades of linguistic theory with a surprising new model of how we process language. Published January 21st in Nature Human Behaviour, the study by Morten H. Christiansen, William R. Professor of Psychology, and Yngwie A. Nielsen of Aarhus University, suggests our brains may not rely on complex, hierarchical grammar to construct sentences. Instead, they propose language is built from pre-assembled chunks—akin to LEGO pieces—of word classes. “I think the main contribution is showing that traditional rules of grammar cannot capture all of the mental representations of language structure,” said Nielsen. This discovery could reshape our understanding of language evolution and even narrow the perceived gap between human and animal communication, as Christiansen notes, “It might even be possible to account for how we use language in general with flatter structure.”

Non-Constituent Sequences Prime Faster Language Processing

The building blocks of language may be simpler than previously imagined, according to a study challenging long-held assumptions about how we process speech. Researchers at Cornell University and Aarhus University have demonstrated that frequently occurring, yet grammatically ‘incomplete’ word sequences – termed non-constituent sequences – are surprisingly efficient at priming language processing. This suggests our brains don’t solely rely on complex hierarchical structures to understand and generate sentences.

Experiments utilizing eye-tracking and analysis of real-world phone conversations revealed these linear chunks of word classes, like “in the middle of the” or “can I have a,” are processed faster upon repeated exposure. “Humans possess a remarkable ability to talk about almost anything, sometimes putting words together into never-before-spoken or -written sentences,” said Morten H. Christiansen, William R. Professor of Psychology at Cornell. This priming effect indicates these sequences are integral to our mental representation of language, operating alongside, or even independent of, traditional grammatical rules.

The prevailing theory, dating back to at least the 1950s, posits a tree-like mental grammar where words combine into larger units called constituents. However, Christiansen and co-author Yngwie A. Nielsen found that “not all sequences of words form constituents,” and that frequently used non-constituents are often overlooked.

Hierarchical Syntax Challenged by Linear Word Chunks

For decades, the prevailing view in linguistics has positioned complex, tree-like mental grammar as fundamental to human language, distinguishing us from other animal communication. However, new research from Cornell University and Aarhus University suggests a surprisingly different architecture may be at play. Researchers are now investigating whether language isn’t built from intricate hierarchies, but rather assembled from pre-fabricated linear sequences—effectively, linguistic LEGO blocks. Nielsen of Aarhus University. Christiansen, William R. Professor of Psychology at Cornell University. Christiansen proposes that a “flatter structure” might adequately explain language use, potentially narrowing the cognitive gap between humans and other species. This challenges the long-held assumption of uniquely complex syntactic structures as the cornerstone of human linguistic capacity.

Mental Representations Beyond Grammar Impact Human-Animal Communication

For decades, the prevailing linguistic theory posited that human language uniquely relies on complex, hierarchical grammar, differentiating us from other species. However, new research challenges this assumption, suggesting our brains may utilize a more streamlined system of pre-assembled linguistic chunks. Nielsen of Aarhus University. Researchers, led by Morten H. Christiansen of Cornell University, utilized eye-tracking and analysis of phone conversations to reveal this “priming” effect—faster processing of previously encountered word sequences. This suggests these linear chunks aren’t simply memorized phrases, but integral components of how we construct meaning.

I think the main contribution is showing that traditional rules of grammar cannot capture all of the mental representations of language structure.

Nielsen