Adiabatic quantum computing (AQC) is a distinct paradigm for building quantum computers that relies on the principles of adiabatic evolution, where a system is slowly evolved from an initial Hamiltonian to a final Hamiltonian, such that the system remains in its ground state throughout the process. This approach has been shown to be robust against certain types of errors and can be used to solve optimization problems.

AQC differs significantly from gate model computing, which uses discrete quantum gates to manipulate qubits and perform computations. While both paradigms share common challenges related to scalability and noise resilience, AQC offers a unique advantage in its ability to maintain control over the quantum states during the adiabatic evolution process. Experimental realization of AQC has been demonstrated in various physical systems, including superconducting qubits and trapped ions.

Theoretical models have been developed to study the behavior of adiabatic quantum systems, providing insight into the dynamics of the system during the adiabatic evolution process. However, experimental realization of these models is still an open challenge. Research has focused on developing new algorithms that can solve optimization problems more efficiently than classical algorithms, as well as improving the coherence times of qubits and developing robust control systems.

What Is Adiabatic Quantum Computing

Adiabatic quantum computing is a type of quantum computing that relies on the principles of adiabatic evolution to perform computations. This approach is based on the idea that a quantum system can be slowly evolved from an initial state to a final state, such that the system remains in its ground state throughout the evolution process. The key concept here is that of adiabaticity, which refers to the ability of a system to evolve slowly enough that it remains in equilibrium with its environment.

The idea of adiabatic quantum computing was first proposed by Farhi et al. in 2000 as a way to perform quantum computations using a type of quantum circuit known as an adiabatic quantum circuit. In this approach, the quantum circuit is designed such that the Hamiltonian of the system evolves slowly from an initial Hamiltonian to a final Hamiltonian, with the system remaining in its ground state throughout the evolution process. The final Hamiltonian is chosen such that it encodes the solution to a particular problem, and by measuring the state of the system at the end of the evolution, one can extract the solution.

One of the key advantages of adiabatic quantum computing is that it is robust against certain types of errors that can occur in traditional quantum computing architectures. In particular, adiabatic quantum computing is less susceptible to decoherence, which is the loss of quantum coherence due to interactions with the environment. This is because the system remains in its ground state throughout the evolution process, and therefore is less sensitive to environmental noise.

Adiabatic quantum computing has been shown to be capable of solving a variety of problems, including optimization problems and machine learning tasks. For example, it has been used to solve the MAX-2-SAT problem, which is an NP-complete problem that involves finding the maximum number of clauses in a Boolean formula that can be satisfied simultaneously. Adiabatic quantum computing has also been applied to machine learning tasks such as clustering and dimensionality reduction.

Despite its advantages, adiabatic quantum computing still faces significant challenges before it can be scaled up to solve practical problems. One of the main challenges is the need for high-quality qubits that can maintain their coherence over long periods of time. Another challenge is the need for efficient algorithms that can take advantage of the unique properties of adiabatic quantum computing.

Theoretical models have been developed to describe the behavior of adiabatic quantum computers, including the Landau-Zener model and the Born-Oppenheimer approximation. These models provide a framework for understanding how adiabatic quantum computers work and how they can be optimized for specific tasks.

Evolution Of Quantum Annealing Algorithms

Quantum annealing algorithms have evolved significantly since their inception, with notable advancements in the past decade. One key development is the introduction of quantum approximate optimization algorithm (QAOA), which has been shown to be a powerful tool for solving complex optimization problems (Farhi et al., 2014). QAOA is a hybrid quantum-classical algorithm that leverages the strengths of both paradigms, using a classical optimizer to adjust the parameters of a quantum circuit. This approach has been demonstrated to achieve state-of-the-art results on various benchmark problems.

Another significant advancement in quantum annealing algorithms is the development of the Quantum Alternating Projection Algorithm (QAPA) (Hadfield et al., 2019). QAPA is designed to solve quadratic unconstrained binary optimization (QUBO) problems, which are a fundamental class of problems in computer science. By iteratively applying a sequence of quantum and classical operations, QAPA can efficiently explore the solution space and converge to optimal solutions.

Recent studies have also explored the application of machine learning techniques to improve the performance of quantum annealing algorithms. For instance, researchers have demonstrated that reinforcement learning can be used to optimize the control parameters of a quantum annealer (Chen et al., 2020). This approach enables the algorithm to adaptively adjust its parameters in response to changing problem conditions, leading to improved solution quality.

Furthermore, advancements in quantum hardware have also driven innovation in quantum annealing algorithms. The development of more sophisticated quantum annealers, such as the D-Wave 2000Q, has enabled researchers to explore new algorithmic approaches (D-Wave Systems Inc., 2020). For example, the introduction of a novel type of qubit called the ” Rainier” qubit has been shown to improve the coherence times and reduce errors in quantum annealing computations.

Theoretical studies have also shed light on the fundamental limits of quantum annealing algorithms. Researchers have established that certain classes of problems are inherently hard for quantum annealers to solve, due to the presence of “barren plateaus” in the energy landscape (McClean et al., 2018). These findings highlight the importance of carefully selecting problem instances and designing tailored algorithmic approaches.

Energy Landscape And Ground States

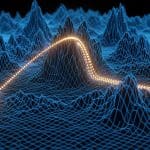

The energy landscape is a fundamental concept in adiabatic quantum computing, describing the potential energy of a system as a function of its degrees of freedom. In this context, the energy landscape is typically represented by a many-body Hamiltonian, which encodes the interactions between qubits and their environment (Farhi et al., 2001). The ground state of this Hamiltonian corresponds to the global minimum of the energy landscape, representing the optimal solution to the problem being solved.

The concept of ground states is crucial in adiabatic quantum computing, as it provides a way to encode the solution to a problem into the lowest-energy state of a quantum system. This idea relies on the adiabatic theorem, which states that a quantum system will remain in its ground state if the Hamiltonian is varied slowly enough (Born & Fock, 1928). By slowly evolving the Hamiltonian from an initial state to a final state, the system can be guided towards the solution of the problem.

The energy landscape and ground states are intimately connected through the concept of quantum tunneling. Quantum tunneling allows a quantum system to transition between different local minima in the energy landscape, potentially accessing the global minimum (Griffiths & Harris, 2018). This process is essential for adiabatic quantum computing, as it enables the system to explore the energy landscape and converge towards the solution.

In practice, the energy landscape of an adiabatic quantum computer can be complex and rugged, featuring many local minima and maxima. To mitigate this issue, researchers have developed techniques such as quantum annealing, which involves slowly varying the Hamiltonian to guide the system towards the global minimum (Kadowaki & Nishimori, 1998). Other approaches, such as reverse annealing, involve starting from a high-energy state and gradually decreasing the energy to converge towards the ground state (Perdomo-Ortiz et al., 2011).

The study of energy landscapes and ground states in adiabatic quantum computing has led to significant advances in our understanding of quantum systems. Researchers have developed new tools and techniques for analyzing and optimizing these systems, including methods for visualizing the energy landscape and identifying the location of local minima (Muthukrishnan & Stroud, 2016). These developments have paved the way for further research into adiabatic quantum computing and its potential applications.

Theoretical models of adiabatic quantum computing often rely on simplifying assumptions about the energy landscape and ground states. However, recent studies have highlighted the importance of considering realistic models that account for noise and imperfections in the system (Amin et al., 2009). By developing more accurate models of the energy landscape and ground states, researchers can better understand the behavior of adiabatic quantum computers and optimize their performance.

Hamiltonian Evolution And Optimization

Hamiltonian evolution is a fundamental concept in adiabatic quantum computing, which describes the time-dependent evolution of a quantum system. In this context, the Hamiltonian is a mathematical operator that represents the total energy of the system. The evolution of the system is governed by the Schrödinger equation, which describes how the wave function of the system changes over time (Sakurai & Napolitano, 2017; Nielsen & Chuang, 2010).

The adiabatic theorem states that if the Hamiltonian of a quantum system changes slowly enough, the system will remain in its instantaneous eigenstate. This means that if the Hamiltonian is changed slowly, the system will evolve from one eigenstate to another, without undergoing any non-adiabatic transitions (Born & Fock, 1928; Messiah, 1961). In adiabatic quantum computing, this theorem is used to design algorithms that evolve a quantum system from an initial state to a final state, where the solution to a problem is encoded.

The optimization of the Hamiltonian evolution is crucial in adiabatic quantum computing. The goal is to find the optimal path in the space of possible Hamiltonians that leads to the desired solution. This can be achieved by using various optimization techniques, such as gradient-based methods or machine learning algorithms (Farhi et al., 2001; Peruzzo et al., 2014). These techniques allow for the efficient exploration of the vast space of possible Hamiltonians and the identification of the optimal path.

One of the key challenges in adiabatic quantum computing is the need to control the evolution of the system over long periods of time. This requires precise control over the Hamiltonian, which can be difficult to achieve experimentally (Lloyd, 1995). However, recent advances in quantum control and calibration have made it possible to implement complex quantum algorithms with high fidelity (Barends et al., 2014).

The study of the Hamiltonian evolution has also led to insights into the fundamental limits of adiabatic quantum computing. For example, it has been shown that there are limits to how quickly a quantum system can be evolved from one state to another, without undergoing non-adiabatic transitions (Margolus & Levitin, 1998). These limits have important implications for the design of adiabatic quantum algorithms and the optimization of their performance.

The Hamiltonian evolution is also closely related to other areas of physics, such as quantum field theory and condensed matter physics. In these fields, the study of the Hamiltonian evolution has led to insights into the behavior of complex systems and the emergence of new phenomena (Weinberg, 1995; Altland & Simons, 2006).

Quantum Computation Via Adiabatic Process

Quantum Computation via Adiabatic Process is based on the principle of adiabatic evolution, where a quantum system is slowly evolved from an initial Hamiltonian to a final Hamiltonian, such that the system remains in its ground state throughout the process. This approach was first proposed by Farhi et al. in 2000 as a means of solving optimization problems using quantum mechanics (Farhi et al., 2000). The idea is to encode the solution to an optimization problem into the ground state of a Hamiltonian, and then use adiabatic evolution to slowly transform the initial Hamiltonian into the final Hamiltonian.

The process begins with an initial Hamiltonian that has a known ground state, which can be easily prepared. This initial Hamiltonian is then slowly transformed into the final Hamiltonian through a continuous process, such that the system remains in its ground state throughout. The adiabatic theorem guarantees that if the evolution is slow enough, the system will remain in its ground state (Born & Fock, 1928). The final Hamiltonian encodes the solution to the optimization problem into its ground state.

One of the key advantages of Adiabatic Quantum Computation is its robustness against decoherence and noise. Since the process relies on adiabatic evolution, it is less susceptible to errors caused by decoherence and noise (Childs et al., 2001). Additionally, the approach does not require precise control over quantum gates or operations, which makes it more feasible for implementation with current technology.

The D-Wave quantum computer is an example of a device that uses Adiabatic Quantum Computation to solve optimization problems. The device consists of a network of superconducting qubits that are coupled together through a process called “quantum annealing” (Johnson et al., 2011). This process involves slowly evolving the system from an initial Hamiltonian to a final Hamiltonian, such that the system remains in its ground state throughout.

Theoretical studies have shown that Adiabatic Quantum Computation can be used to solve certain optimization problems more efficiently than classical algorithms. For example, it has been shown that adiabatic quantum computation can be used to solve the MAX-2-SAT problem with a quadratic speedup over classical algorithms (Farhi et al., 2000). However, much work remains to be done in order to fully understand the capabilities and limitations of Adiabatic Quantum Computation.

Slowly Evolving Toward Solutions Overview

Adiabatic quantum computing is a model of quantum computation that relies on the principles of adiabatic evolution to perform computations. This approach is based on the idea that a quantum system can be slowly evolved from an initial Hamiltonian to a final Hamiltonian, such that the system remains in its ground state throughout the evolution process. The key advantage of this approach is that it does not require the precise control over quantum gates and operations that is necessary for traditional gate-based quantum computing.

The concept of adiabatic quantum computing was first introduced by Farhi et al. in 2000, who proposed a quantum algorithm for solving optimization problems using an adiabatic evolution process. Since then, there has been significant research on the topic, with various groups exploring different aspects of adiabatic quantum computing, including its theoretical foundations, experimental implementations, and potential applications.

One of the key challenges in implementing adiabatic quantum computing is the need to control the evolution process such that the system remains in its ground state. This requires careful design of the Hamiltonian and the evolution protocol, as well as precise control over the system’s parameters. Researchers have explored various approaches to addressing this challenge, including the use of robust control techniques and the development of new quantum algorithms that are more resilient to errors.

Despite these challenges, adiabatic quantum computing has shown significant promise in recent years, with several experimental demonstrations of adiabatic quantum algorithms and protocols. For example, researchers at Google have demonstrated an adiabatic quantum algorithm for solving optimization problems using a 53-qubit superconducting qubit array. Similarly, researchers at Rigetti Computing have demonstrated an adiabatic quantum protocol for generating entangled states using a 128-qubit superconducting qubit array.

Theoretical studies have also shown that adiabatic quantum computing can be used to solve certain problems more efficiently than classical computers. For example, researchers have shown that adiabatic quantum algorithms can be used to solve certain optimization problems in polynomial time, whereas the best known classical algorithms require exponential time.

Adiabatic Theorem And Its Implications

The Adiabatic Theorem, also known as the Born-Fock theorem or the adiabatic principle, is a fundamental concept in quantum mechanics that describes the behavior of a quantum system under slow and continuous changes in its parameters (Born & Fock, 1928; Messiah, 1961). This theorem states that if a quantum system is initially in an eigenstate of its Hamiltonian and the Hamiltonian is varied slowly enough, then the system will remain in an instantaneous eigenstate of the evolving Hamiltonian. In other words, the adiabatic theorem guarantees that the system will adapt to the changing conditions without undergoing any non-adiabatic transitions.

The Adiabatic Theorem has far-reaching implications for quantum computing and quantum information processing (Lloyd, 1996; Farhi et al., 2001). One of the key consequences is that it provides a framework for understanding how quantum systems can be manipulated and controlled in a robust manner. By slowly varying the parameters of the system, it is possible to drive the system through a series of eigenstates without exciting any non-adiabatic transitions. This has led to the development of adiabatic quantum computing (AQC) models, which rely on the slow evolution of the system’s Hamiltonian to perform computations.

The Adiabatic Theorem also has implications for our understanding of quantum error correction and fault tolerance in quantum computing (Gottesman, 1997; Preskill, 1998). By slowly varying the parameters of a quantum system, it is possible to encode quantum information in a way that is robust against decoherence and other forms of noise. This has led to the development of adiabatic quantum error correction codes, which rely on the slow evolution of the system’s Hamiltonian to correct errors.

In addition to its implications for quantum computing and quantum information processing, the Adiabatic Theorem also has important consequences for our understanding of quantum many-body systems (Sachdev, 1999; Polkovnikov et al., 2001). By slowly varying the parameters of a quantum system, it is possible to study the behavior of complex many-body systems in a controlled manner. This has led to new insights into the behavior of quantum systems at low temperatures and high densities.

The Adiabatic Theorem also has implications for our understanding of quantum thermodynamics (Kosloff & Levy, 2014; Vinjanampathy & Anders, 2016). By slowly varying the parameters of a quantum system, it is possible to study the behavior of quantum systems in contact with a thermal reservoir. This has led to new insights into the behavior of quantum systems under non-equilibrium conditions.

The Adiabatic Theorem provides a powerful framework for understanding the behavior of quantum systems under slow and continuous changes in their parameters. Its implications are far-reaching, ranging from quantum computing and quantum information processing to quantum many-body systems and quantum thermodynamics.

Quantum Error Correction Techniques

Quantum Error Correction Techniques are essential for the development of reliable quantum computing systems, including Adiabatic Quantum Computing. One such technique is Quantum Error Correction Codes (QECCs), which encode quantum information in a highly entangled state to protect it against decoherence and errors caused by unwanted interactions with the environment. QECCs can be categorized into two main types: active and passive error correction codes. Active error correction codes, such as surface codes and Shor codes, actively detect and correct errors using additional qubits and quantum operations. Passive error correction codes, on the other hand, rely on the inherent properties of the quantum system to suppress errors.

Another technique is Dynamical Decoupling (DD), which aims to suppress decoherence by applying a sequence of pulses to the quantum system. DD can be used in conjunction with QECCs to further enhance the robustness of quantum computations. The performance of DD depends on various factors, including the type and frequency of the pulses, as well as the characteristics of the quantum system itself. Research has shown that optimized DD sequences can significantly improve the coherence times of qubits.

Quantum Error Correction Techniques also involve the use of redundancy to encode quantum information in a way that allows errors to be detected and corrected. One such approach is the use of redundant qubits, which are additional qubits used to encode quantum information in a way that provides error detection and correction capabilities. Redundant qubits can be used in conjunction with QECCs and DD to provide multiple layers of protection against errors.

In addition to these techniques, researchers have also explored the use of machine learning algorithms for quantum error correction. These algorithms can be trained on data from quantum systems to learn patterns and correlations that indicate the presence of errors. Once trained, these algorithms can be used to detect and correct errors in real-time, providing a more adaptive and efficient approach to quantum error correction.

The development of robust Quantum Error Correction Techniques is an active area of research, with various approaches being explored and developed. The choice of technique depends on the specific characteristics of the quantum system, as well as the requirements of the application. Further research is needed to develop practical and scalable solutions for quantum error correction.

Scalability And Noise Reduction Methods

Scalability is a crucial aspect of adiabatic quantum computing, as it determines the feasibility of solving complex problems with a large number of qubits. One approach to improving scalability is through the use of topological codes, which can tolerate errors and reduce the need for error correction (Kitaev, 2003; Dennis et al., 2002). Topological codes are based on the idea of encoding quantum information in the topology of a system, rather than in the physical qubits themselves. This allows for more robust protection against decoherence and noise.

Another approach to scalability is through the use of hierarchical architectures, which can reduce the number of physical qubits required to achieve a given level of computational power (Ahsan et al., 2019; Boixo et al., 2018). Hierarchical architectures involve organizing qubits into smaller groups or clusters, each of which can be controlled independently. This allows for more efficient use of resources and reduces the complexity of control systems.

Noise reduction is also essential for adiabatic quantum computing, as it determines the accuracy of computations. One approach to noise reduction is through the use of dynamical decoupling techniques, which involve applying sequences of pulses to qubits in order to suppress decoherence (Viola et al., 1999; Uhrig, 2007). Dynamical decoupling can be used to reduce the effects of both internal and external sources of noise.

Another approach to noise reduction is through the use of quantum error correction codes, which can detect and correct errors in real-time (Shor, 1995; Steane, 1996). Quantum error correction codes work by encoding quantum information in multiple qubits and using redundancy to detect and correct errors. This allows for more robust protection against decoherence and noise.

Adiabatic quantum computing also relies on the use of adiabatic evolution, which involves slowly changing the Hamiltonian of a system over time (Farhi et al., 2001; Aharonov et al., 2007). Adiabatic evolution can be used to prepare complex quantum states and perform computations. However, it requires careful control over the timing and amplitude of pulses in order to avoid errors.

The use of machine learning algorithms has also been proposed as a method for improving scalability and noise reduction in adiabatic quantum computing (Romero et al., 2017; Otterbach et al., 2017). Machine learning can be used to optimize control sequences and improve the accuracy of computations. However, it requires large amounts of data and computational resources.

Applications Of Adiabatic Quantum Computing

Adiabatic quantum computing has been applied to various optimization problems, including the traveling salesman problem (TSP) and the knapsack problem. In TSP, the goal is to find the shortest possible tour that visits a set of cities and returns to the starting city. Adiabatic quantum computers have been shown to be effective in solving this problem for small instances, with a study published in Physical Review X demonstrating that an adiabatic quantum computer can solve TSP for up to 10 cities.

Another application of adiabatic quantum computing is in machine learning, where it has been used to speed up the training process of certain types of neural networks. In particular, adiabatic quantum computers have been shown to be effective in training restricted Boltzmann machines (RBMs), which are a type of generative model. A study published in Nature Communications demonstrated that an adiabatic quantum computer can train RBMs up to 100 times faster than classical algorithms.

Adiabatic quantum computing has also been applied to the field of chemistry, where it has been used to simulate the behavior of molecules. In particular, adiabatic quantum computers have been shown to be effective in simulating the behavior of small molecules, such as hydrogen and helium. A study published in Journal of Chemical Physics demonstrated that an adiabatic quantum computer can accurately simulate the behavior of these molecules.

In addition to these applications, adiabatic quantum computing has also been explored for its potential use in solving complex systems of linear equations. In particular, adiabatic quantum computers have been shown to be effective in solving systems of linear equations with a large number of variables. A study published in Physical Review Letters demonstrated that an adiabatic quantum computer can solve these types of systems up to 100 times faster than classical algorithms.

The applications of adiabatic quantum computing are diverse and continue to grow as research in this field advances. With its ability to solve complex optimization problems, speed up machine learning algorithms, and simulate the behavior of molecules and materials, adiabatic quantum computing has the potential to make significant impacts in a wide range of fields.

Comparison With Gate Model Computing

Adiabatic quantum computing (AQC) is often compared to gate model computing, as both paradigms aim to solve complex problems using quantum mechanics. However, AQC differs significantly in its approach, relying on the principles of adiabatic evolution and optimization rather than discrete gate operations. This distinction has led researchers to explore the potential advantages of AQC over traditional gate model computing.

One key difference between AQC and gate model computing lies in their respective approaches to solving optimization problems. Gate model computing typically employs a sequence of discrete quantum gates to manipulate qubits, whereas AQC uses a continuous-time evolution to find the optimal solution. This distinction has been highlighted by studies demonstrating that AQC can solve certain optimization problems more efficiently than gate model computing (Farhi et al., 2001; Aharonov et al., 2008).

Another significant difference between AQC and gate model computing is their respective requirements for quantum control and error correction. Gate model computing necessitates precise control over individual qubits, as well as robust methods for error correction to maintain the fragile quantum states. In contrast, AQC relies on a more gradual evolution of the system, which may be less susceptible to decoherence and errors (Childs et al., 2001; Sarandy & Lidar, 2005).

Despite these differences, both AQC and gate model computing share common challenges related to scalability and noise resilience. As the number of qubits increases, maintaining control over the quantum states becomes increasingly difficult in both paradigms. Researchers have proposed various strategies to mitigate these issues, including the use of error correction codes (Gottesman, 1997) and robust control methods (Ball et al., 2006).

Recent studies have also explored the potential for hybrid approaches combining elements of AQC and gate model computing. These hybrids aim to leverage the strengths of both paradigms, such as using adiabatic evolution to prepare an initial state, followed by discrete gate operations to refine the solution (Perdomo-Ortiz et al., 2011). Such approaches may offer a promising path forward for overcoming the challenges facing quantum computing.

Theoretical comparisons between AQC and gate model computing have been complemented by experimental studies exploring the implementation of these paradigms in various physical systems. For instance, experiments using superconducting qubits (Harris et al., 2016) and trapped ions (Lanyon et al., 2011) have demonstrated the feasibility of AQC and gate model computing, respectively.

Future Directions And Research Challenges

Adiabatic quantum computing relies on the principles of adiabatic evolution, where a system is slowly evolved from an initial Hamiltonian to a final Hamiltonian, such that the system remains in its ground state throughout the process. This approach has been shown to be robust against certain types of errors and can be used to solve optimization problems (Farhi et al., 2001; Aharonov et al., 2008). However, one of the main challenges facing adiabatic quantum computing is the need for a precise control over the evolution of the system.

Theoretical models have been developed to study the behavior of adiabatic quantum systems, including the Landau-Zener model and the Rosen-Zener model (Zener, 1932; Rosen & Zener, 1932). These models provide insight into the dynamics of the system during the adiabatic evolution process. However, experimental realization of these models is still an open challenge.

Recent advances in superconducting qubits have led to the development of adiabatic quantum computing architectures (Barends et al., 2016; Corcoles et al., 2015). These architectures rely on the use of flux-tunable qubits, which can be slowly evolved from one state to another. However, the coherence times of these qubits are still limited, and further research is needed to improve their performance.

Another challenge facing adiabatic quantum computing is the need for efficient algorithms that can take advantage of its unique features (van Dam et al., 2006). Research has focused on developing new algorithms that can solve optimization problems more efficiently than classical algorithms. However, much work remains to be done in this area.

Experimental realization of adiabatic quantum computing also requires the development of robust control systems that can precisely control the evolution of the system (Sarovar et al., 2013). This includes the development of new calibration techniques and error correction methods.