Indian farmers could soon benefit from dramatically boosted crop yields thanks to a new $5 million grant awarded to Professor Venkatesan Sundaresan and his team. The Gates Foundation funding, announced January 27, 2026, will expand revolutionary “self-cloning” seed technology – initially developed for rice – to vital Indian staples like pearl millet and Indian mustard. This breakthrough allows farmers to replant seeds from high-yielding hybrid varieties without losing productivity, a major hurdle for smallholder farms. “It’s wonderful that the Gates Foundation has taken an interest in this technology,” said Sundaresan, a Distinguished Professor at UC Davis. “Their funding makes it possible for us to apply our method to specific crops in contexts where it can make a difference.”

$4.9 Million Grant Expands Synthetic Apomixis to Indian Crops

A $4.9 million, five-year grant from the Gates Foundation will propel research into self-cloning crop technology, specifically targeting staples vital to Indian agriculture—pearl millet and Indian mustard. Professor Venkatesan Sundaresan at the University of California, Davis, leads the collaborative project alongside researchers at UC Berkeley, ICAR-IARI in New Delhi, and IISER-Thiruvananthapuram, aiming to sustainably enhance yields for smallholder farmers. This expansion builds upon previously successful development of “synthetic apomixis” in rice, a process allowing plants to reproduce asexually, effectively cloning themselves.

These regionally crucial crops, unlike globally traded commodities, often receive limited research funding, a disparity the grant seeks to address. “Big seed companies generally want to work on huge worldwide crops like corn, soybeans and tomatoes,” said Sundaresan, highlighting the project’s focus on benefitting farmers in developing nations. Hybrid varieties, known for high yields, currently require annual seed purchases as their genetic advantages diminish with each generation; synthetic apomixis promises to stabilize these traits, allowing farmers to replant saved seeds.

Extending the technology to Indian mustard presents a unique challenge, as it’s a dicot—related to cabbage and broccoli—differing significantly from the monocot grasses where synthetic apomixis has already proven successful. “It may be more complicated to move this technology into dicots, because the embryo initiation process is a little different,” Sundaresan acknowledged, “but I’m hoping that in five years, we’ll have the technology working in Indian mustard.” Crucially, the team also aims to eliminate the need for transgenic modifications, relying instead on gene editing techniques to ensure wider regulatory acceptance, especially given India’s recent deregulation of gene-edited crops. “The time is right to develop these crops in India,” Sundaresan stated.

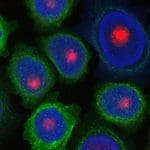

Synthetic Apomixis Adapts to Monocot & Dicot Embryonic Development

A $5 million grant from the Gates Foundation is fueling research to expand the application of “synthetic apomixis” – a self-cloning technology – beyond previously successful trials in rice and maize, now targeting regionally vital crops in India like pearl millet and Indian mustard. This circumvents the need to annually purchase new hybrid seeds, a significant cost for smallholder farmers. Beyond broadening the technology’s applicability, the team intends to eliminate the use of transgenics—introducing foreign DNA—in favor of solely utilizing gene editing techniques like CRISPR/Cas9.

Gene Editing Aims to Eliminate Transgenics in Self-Cloning Seeds

The core of this effort lies in “synthetic apomixis,” a technique previously demonstrated in rice, allowing farmers to retain superior genetics across generations without annual seed purchases. This is particularly crucial for regionally important crops that “do not usually receive international research attention.”

The project isn’t simply about replicating success in new species; it’s actively seeking to eliminate the use of transgenic methods. Currently, synthetic apomixis can involve inserting foreign DNA, but researchers are now pivoting towards a purely gene-editing approach, utilizing tools like CRISPR/Cas9 to modify existing genes. “A tweak to remove transgenics” is a key objective, as gene-edited crops face less regulatory scrutiny than those containing foreign genes, especially in light of India’s recent deregulation of such crops.