Understanding when quantum computers will surpass classical computers, achieving what’s known as quantum economic advantage, remains a crucial challenge for scientists, policymakers, and industry leaders, and a team led by Frederick Mejia, Hans Gundlach, and Jayson Lynch from FutureTech Lab at MIT addresses this directly. They introduce a publicly available online calculator that systematically estimates the point at which quantum systems outperform their classical counterparts for specific computational problems, a tool built upon existing analytical frameworks. This calculator allows users to explore how various technical factors, such as error correction and gate speeds, influence these estimates, and to compare results based on different hardware development roadmaps and application requirements. The research demonstrates that the timing of quantum advantage is surprisingly robust for some problems, while for others, it hinges critically on achieving specific technical milestones, offering valuable insights into the path towards practical quantum computation.

However, creating such a view presents a significant challenge because quantum advantage analyses depend on both algorithm properties and technical characteristics, including error correction and gate speeds. Different analyses routinely make different assumptions about these characteristics, creating inconsistencies and hindering clear comparisons. Consequently, a comprehensive understanding of the interplay between algorithmic advances and underlying hardware limitations remains elusive, impeding informed decision-making in both research investment and strategic planning.

Shor’s Algorithm and Quantum Chemistry Applications

Researchers have analyzed the parameters and assumptions used in quantum computing roadmap analyses, focusing on the algorithms considered, hardware assumptions, error correction, and predicted timelines. The primary driver for quantum computing development is the potential to break current encryption algorithms by efficiently factoring large numbers, a task addressed by Shor’s algorithm. Quantum computers also hold promise for revolutionizing computational chemistry and materials science by simulating molecular interactions and discovering new materials. The goal of this analysis is to estimate when quantum computers will be powerful enough to threaten current cryptography or deliver a significant advantage in these scientific fields.

Shor’s algorithm requires approximately three qubits for every digit of the number being factored. Grover’s algorithm, used for database search, provides a quadratic speedup over classical algorithms. Variational Quantum Eigensolver (VQE) and Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm (QAOA) are algorithms used for quantum chemistry and optimization problems, potentially achievable with fewer qubits. A central metric is the number of logical qubits, error-corrected qubits, needed for specific tasks. The number of physical qubits required to create a single logical qubit is a critical factor, potentially reaching thousands depending on qubit quality and the error correction scheme.

Qubit connectivity, coherence time, and gate fidelity also play important roles; limited connectivity increases computational overhead, while longer coherence times and higher fidelity reduce errors. Quantum Volume, a metric combining these factors, provides a comprehensive assessment of quantum computer performance. Current and near-term quantum computing platforms, including IBM Quantum, IonQ, and QuEra, are actively being developed. Error correction is essential for building large-scale, reliable quantum computers, but it requires significant overhead in terms of physical qubits. Surface codes are a leading error correction scheme, and the Threshold Theorem suggests that error correction can suppress errors exponentially if the error rate of physical qubits is below a certain threshold.

The ultimate goal is to build fault-tolerant quantum computers that can operate reliably even in the presence of errors. Factoring a 2048-bit RSA key, the benchmark for breaking current cryptography, requires approximately 6144 logical qubits. Near-term quantum computers will likely have hundreds or a few thousand physical qubits, suitable for exploring algorithms and solving small problems. Mid-term computers, within five to ten years, may have thousands of physical qubits and a few hundred logical qubits, potentially demonstrating quantum advantage for specific problems but not yet breaking cryptography.

Long-term computers, beyond ten years, will require millions of physical qubits and thousands of logical qubits to break RSA-2048, presenting a significant engineering challenge. The timeline for breaking RSA is uncertain, but likely at least a decade away, and potentially much longer. The analysis assumes continued progress in qubit quality, scalability of error correction, and algorithm development, acknowledging that hardware diversity and classical computing advances will also influence progress.

Predicting Quantum Advantage Across Problem Types

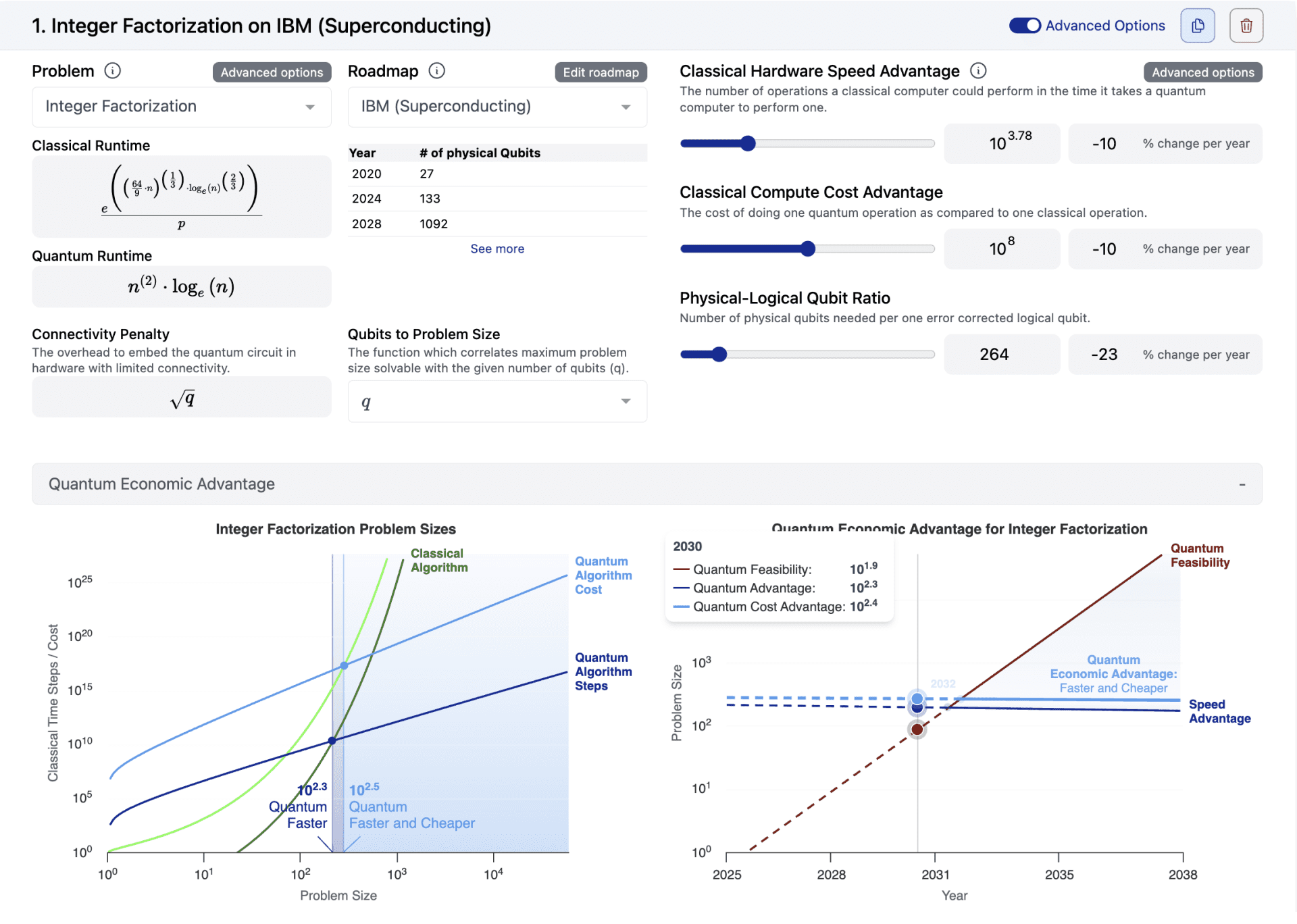

Researchers have developed a web-based tool, the Quantum Economic Advantage Calculator, to predict when quantum computers will surpass classical computers for specific computational problems. This tool calculates the timing of quantum outperformance by considering technical characteristics like error correction, gate speeds, and qubit connectivity, allowing for easy comparison across different analyses and hardware roadmaps. The framework allows users to update assumptions regarding these characteristics, tailoring predictions to specific applications and hardware types. Comparative analyses on integer factorization and database search, using IBM’s superconducting system, IonQ’s ion-trap computer, and QuEra’s neutral atom system, were performed.

For integer factorization, the analysis indicates that IBM hardware is projected to be capable of breaking 2048-bit encryption around 2034, assuming continued improvements in qubit technology. This prediction is based on extrapolating current trends in physical-logical qubit ratios and improvement rates. The researchers found that IBM’s superconducting qubits exhibit a hardware slowdown, due to gate times of 12 nanoseconds, while IonQ’s ion-trap system has a slower gate speed of 600,000 nanoseconds. QuEra’s neutral atom system falls in between, with a 250 nanosecond gate speed. Assuming a consistent improvement rate of 23% per year in the physical-logical qubit ratio and a 10% annual decline in both quantum slowdowns and cost overhead, the team projected the years when quantum economic advantage would be achieved for each problem and hardware type. These projections demonstrate the tool’s ability to assess the interplay between hardware capabilities and algorithmic performance, providing valuable insights for researchers, policymakers, and business leaders.

Quantum Advantage Timelines and Development Strategies

The Quantum Economic Advantage Calculator represents a practical tool for exploring the timelines for quantum advantage and how different development approaches influence them. Built upon the Classical Hare and Quantum Tortoise framework, the calculator translates theoretical concepts into a customizable model, allowing users to analyze various scenarios and assumptions regarding quantum hardware and algorithms. By incorporating new inputs and capabilities, the tool expands the scope of quantum economic advantage (QEA) analysis, providing a more detailed understanding of the factors driving quantum advantage. Initial analyses using the calculator suggest potential applications of quantum computing emerging in the 2030s.

Importantly, the tool highlights that the critical factors for achieving advantage depend on the specific algorithm; qubit numbers are most important for algorithms like Shor’s, while quantum computer speed is more crucial for algorithms like Grover’s search. The authors acknowledge that the calculator predicts the first year any quantum advantage could be found, not necessarily when advantage will be realized for a specific problem size. Future work could focus on refining these predictions and exploring the impact of data loading challenges, which currently necessitate the use of Quantum Random Access Memory (QRAM) for certain problems. Ultimately, the calculator’s adaptability and accessibility empower researchers and stakeholders to better understand and navigate the evolving landscape of quantum computing.

👉 More information

🗞 Introducing the Quantum Economic Advantage Online Calculator

🧠 ArXiv: https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.21031