A team of researchers led by Cindy Regal of JILA and the University of Colorado Boulder has made significant strides in unraveling the complexities of light-assisted atomic collisions. This study, published in Physical Review Letters, offers new insights into the rates at which these collisions occur under varying circumstances, particularly when considering small atomic energy splittings known as hyperfine structures.

The research, conducted in collaboration with Jose D’Incao (former JILA Associate Fellow and now an assistant professor of physics at the University of Massachusetts, Boston), utilizes optical tweezers to isolate and study individual pairs of atoms. By applying a carefully controlled pulse of laser light to drive collisions between the atoms, the team was able to map out the influence of hyperfine structure in these collisions, a challenge that had previously eluded comprehensive theoretical understanding.

The findings could have far-reaching implications for controlling atoms more effectively in applications such as emulating quantum systems using arrays of atoms and molecules. By understanding the intricacies of light-assisted collisions, researchers may be able to advance laser-cooling techniques, molecular quantum science, and the development of future quantum-based technologies.

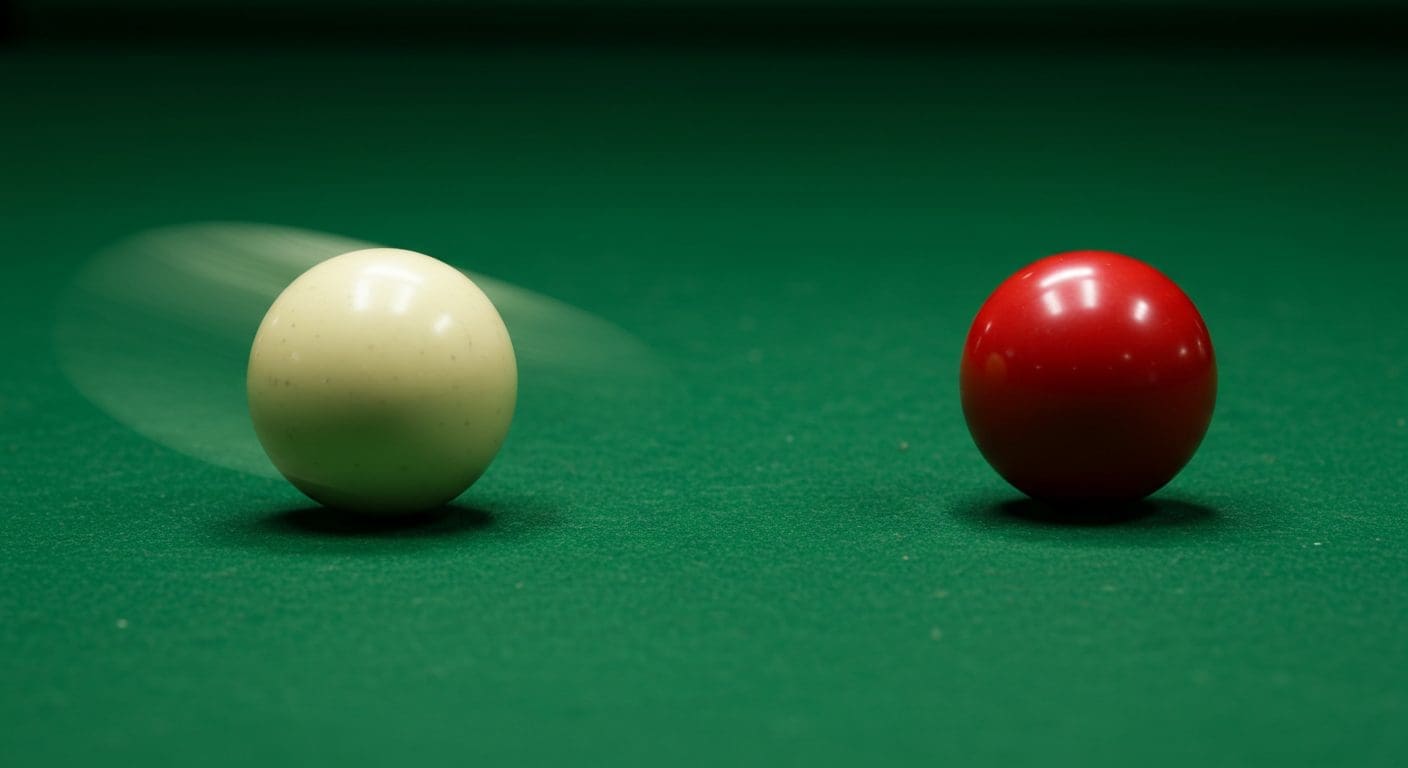

The experiment was conducted by a team led by Cindy Regal, JILA Fellow and University of Colorado Boulder physics professor, and Jose D’Incao, former JILA Associate Fellow now an assistant professor of physics at the University of Massachusetts, Boston. They used optical tweezers, focused lasers capable of trapping and manipulating tiny particles, as their quantum billiard table.

The team applied a collisional laser light to drive collisions between two atoms. This excites the atoms, creating a quantum superposition state where either atom could have absorbed a photon, but it is unclear which one. In this state, electronic forces act at much larger distances than they otherwise would and give the atoms such a large amount of kinetic energy that they escape the trap.

By varying the frequency of the collisional light, the team was able to measure the loss rates of the atoms quantitatively and in relation to hyperfine effects, something that had never been done before. This process allowed them to map out the influence of hyperfine structure in these collisions.

During the experiments, the team developed a novel imaging technique to accurately determine if both atoms remained in the trap after a collision. This technique was crucial because standard imaging methods would inadvertently kick both atoms out of the trap during the collision.

The researchers also developed a theoretical model to understand their experimental results, particularly why setting the light frequency to be close to that of certain hyperfine states resulted in different rates than other hyperfine states.

These findings could influence various endeavors with trapped neutral atoms such as quantum computing, metrology, and many-body physics, where controlling atomic collisions is essential for success. The ability to predict how atomic collisions will behave based on their hyperfine structure will likely be helpful for advancing laser-cooling techniques, molecular quantum science, and the next generation of quantum-based technologies.

External Link: Click Here For More