Researchers from the University of Chicago, Argonne National Laboratory, and Cambridge University have made a breakthrough in quantum network engineering. By “stretching” thin films of diamond, they created quantum bits (qubits) that can operate with less equipment and expense. The technique also makes the qubits easier to control. The team’s findings, published in Physical Review X, could make future quantum networks more feasible. The qubits can now hold their coherence at temperatures up to -452°F, and can be controlled with microwaves, increasing their reliability to 99%. The research was led by Alex High from the Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering.

Quantum Network Advancements: Diamond Dilation and Qubits

Researchers from the University of Chicago, Argonne National Laboratory, and Cambridge University have made significant strides in quantum network engineering. They have developed a method to “stretch” thin films of diamond, creating quantum bits, or qubits, that can operate with less equipment and at a reduced cost. This technique also makes the qubits easier to control. The findings were published in Physical Review X on November 29.

Qubits have unique properties that make them of interest to scientists exploring the future of computing networks. For instance, they could be made virtually impervious to hacking attempts. However, there are significant challenges to overcome before this technology can become widespread. One of the main issues lies within the “nodes” that would relay information along a quantum network. The qubits that make up these nodes are very sensitive to heat and vibrations, requiring them to be cooled down to extremely low temperatures to function.

The Role of Diamonds in Quantum Computing

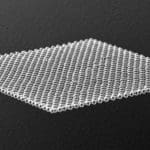

One of the most promising types of qubits is made from diamonds, known as Group IV color centers. These qubits are known for their ability to maintain quantum entanglement for relatively long periods, but to do so they must be cooled down to just above absolute zero. The team experimented with the structure of the material to see what improvements they could make. They found that they could “stretch” out the diamond at a molecular level if they laid a thin film of diamond over hot glass. As the glass cools, it shrinks at a slower rate than the diamond, slightly stretching the diamond’s atomic structure.

The Impact of Diamond Stretching on Qubits

This stretching, though it only moves the atoms apart an infinitesimal amount, has a dramatic effect on how the material behaves. Firstly, the qubits could now hold their coherence at temperatures up to 4 Kelvin (or -452°F). That’s still very cold, but it can be achieved with less specialized equipment. Secondly, the change also makes it possible to control the qubits with microwaves. Previous versions had to use light in the optical wavelength to enter information and manipulate the system, which introduced noise and meant the reliability wasn’t perfect. By using the new system and the microwaves, however, the fidelity went up to 99%.

Bridging the Dilemma in Quantum Computing

It’s unusual to see improvements in both these areas simultaneously. “Usually if a system has a longer coherence lifetime, it’s because it’s good at ‘ignoring’ outside interference—which means it is harder to control, because it’s resisting that interference,” said Xinghan Guo, a Ph.D. student in physics in High’s lab and first author on the paper. “It’s very exciting that by making a very fundamental innovation with materials science, we were able to bridge this dilemma.”

The Future of Quantum Networks

The researchers believe that by understanding the physics at play for Group IV color centers in diamond, they have successfully tailored their properties to the needs of quantum applications. “With the combination of prolonged coherent time and feasible quantum control via microwaves, the path to developing diamond-based devices for quantum networks is clear for tin vacancy centres,” added Mete Atature, a professor of physics with Cambridge University and a co-author on the study. This breakthrough could make future quantum networks more feasible, reducing the resources needed to operate them.

“This technique lets you dramatically raise the operating temperature of these systems, to the point where it’s much less resource-intensive to operate them,” said Alex High, assistant professor with the Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering, whose lab led the study.

“Most qubits today require a special fridge the size of a room and a team of highly trained people to run it, so if you’re picturing an industrial quantum network where you’d have to build one every five or 10 kilometers, now you’re talking about quite a bit of infrastructure and labor,” explained High. “It’s an order of magnitude difference in infrastructure and operating cost,” High said.

“Usually if a system has a longer coherence lifetime, it’s because it’s good at ‘ignoring’ outside interference—which means it is harder to control, because it’s resisting that interference,” said Xinghan Guo, a Ph.D. student in physics in High’s lab and first author on the paper. “It’s very exciting that by making a very fundamental innovation with materials science, we were able to bridge this dilemma.”

“By understanding the physics at play for Group IV color centers in diamond, we successfully tailored their properties to the needs of quantum applications,” said Argonne National Laboratory scientist Benjamin Pingault, also a co-author on the study.

“With the combination of prolonged coherent time and feasible quantum control via microwaves, the path to developing diamond-based devices for quantum networks is clear for tin vacancy centres,” added Mete Atature, a professor of physics with Cambridge University and a co-author on the study.

Summary

Researchers from the University of Chicago, Argonne National Laboratory and Cambridge University have made a significant breakthrough in quantum network engineering by ‘stretching’ thin films of diamond to create quantum bits that can operate with less equipment and expense. This technique allows the quantum bits to hold their coherence at higher temperatures and be controlled with microwaves, potentially making future quantum networks more feasible and less resource-intensive.

- Researchers from the University of Chicago, Argonne National Laboratory, and Cambridge University have made a significant breakthrough in quantum network engineering.

- The team has developed a method to “stretch” thin films of diamond, creating quantum bits (qubits) that can operate with less equipment and at a lower cost.

- This technique also makes the qubits easier to control and could make future quantum networks more feasible.

- Qubits are sensitive to heat and vibrations, requiring cooling to extremely low temperatures to function. The new method allows qubits to hold their coherence at temperatures up to -452°F, which can be achieved with less specialized equipment.

- The change also enables the control of qubits with microwaves, increasing the reliability of the system to 99%.

- The research was led by Alex High, assistant professor with the Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering, and involved scientists from Argonne National Laboratory and Cambridge University.

- The findings were published in the Physical Review X on November 29.

- The researchers used the Pritzker Nanofabrication Facility and Materials Research Science and Engineering Center at the University of Chicago for their study.